Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD1 and Paraschiva Florescu2

1 Founder, Alliance for Natural Health; executive & scientific director, ANH Intl and USA

2 Mission Facilitator, ANH Intl

Nature in crisis

Nature is indeed in crisis, a crisis of survival. And it’s not all about climate change.

Over 200 leading health journals are calling for world leaders to recognise that the primary threat to our planet is not necessarily ‘climate change’, but the ongoing loss of biodiversity.

The global biomass and species abundance of wild mammals has fallen by 82% since prehistory. The 2022 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reveals staggering losses of biodiversity, including, in terrestrial systems, a 23% decline in biotic integrity (the abundance of naturally-present species), with 25% of known species being threatened with extinction.

The rate of species extinction appears at present to be tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the past ten million years, hence it being referred to by David Attenborough and others as the sixth mass extinction. This extinction threatens not only millions of animal and plant species, it is also the first time in history that the survival of our own species — at least in its natural, unengineered form — is threatened. With a wider sense of self-awareness, it’s not difficult to interpret what we’re doing as a form of self sabotage. Some might argue that’s exactly the point, assuming the point is to prepare the way for a transhuman or posthuman future.

In the minds of many, climate change, a process inexorably linked to excessive concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide produced through human activity, is seen as the nexus of everything that’s going wrong with our environment including the recent free fall in biodiversity. The two issues, climate and biodiversity, have almost become synonymous in people’s minds, reducing people’s focus and attention on the multitude of reasons—other than climate change—that are driving the downward spiral of different life forms co-habiting our planet.

Arguing that there is no environmental crisis, and that whatever perturbations or natural cycles might be ongoing don’t pose any risks to our or other species, is a tough ask for anyone who is prepared to scour the ecological literature. By contrast, arguing against climate change being the main driver of biodiversity loss, is a much easier argument. That’s because of the sheer volume of data that points to factors like habitat loss and fragmentation, chemical pollution (of land, air and waters), invasive species and overexploitation and accelerated climate changes as highly significant contributing factors. Yet there are other putative factors, such as exposure to increased electrosmog (anthropogenic electromagnetic fields), and light pollution the importance of which is often ignored or underrepresented.

>>> Read more about our Electrosmog campaign

Disproportionate emphasis

Google gives us some idea of the relative emphasis that’s been placed on climate change versus biodiversity loss. Google brings up 2,550,000,000 results when searching ‘climate change’ and a mere 11% of this (221,000,000) with ‘biodiversity loss’. Climate change is mediated by the global emissions of greenhouse gases (measured as carbon dioxide equivalents).

The entire Net Zero strategy from the United Nations (UN) makes its mission to create a “liveable climate” by cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible by 2030. This agenda again prioritises the climate change agenda over all other influences and dismisses the complexity of ongoing planetary processes, both those linked to, and not linked to, humans and human activity, on Earth. It also trivialises the interconnectedness of all biological, chemical and energetic processes and the need to look at the biosphere as a whole, interacting within an even bigger extra-planetary system.

It ignores issues such as the destruction of diverse habitats, along with the degradation of biodiversity, pollution of the environment as a whole and the impact technological innovations, designed to counteract such impacts, have on both human and environmental health. On top of that, realistically, the financial implications of the implementation of Net Zero means no country will be able to afford to continue the programme. For example, Australia is set to spend $9 trillion over the next 40 years, as shown in this report written by Robin Batterham, the chair of the Net Zero Australia project. It seems that even the supporters of Net Zero are doubting the realistic implications of their project.

“The scale, cost, ambition and potential disruption of achieving net zero by 2050 is unprecedented and immense”, says Batterham.

>>> ANH Feature: Planet in crisis – looking beyond climate change

Despite various academics, and media influencers such as David Attenborough drawing attention to the sixth mass extinction and biodiversity loss, the media is still catastrophising about climate ‘change’ whilst the UN is working on developing solutions using AI to tackle climate change and global warming.

Global agenda

We are constantly being led to believe these problems are existential and there is nothing we can do about them unless we subscribe to the global programmes being developed by the UN such as the 17 Sustainable Development Goals that aim towards “tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests”.

These agencies work together with specific NGOs like the World Economic Forum (WEF) and Gates-funded universities, which push such initiatives as carbon credits which seem to be rapidly losing favour and money and latterly biodiversity and plastic credits (to offset plastic manufacturer/use) to greenwashing the continued pollution and degradation of the environment.

The Biodiversity Credit Alliance (BCA) was set up by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and UK based Soros-funded think tank International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), after the COP15 meeting last year in an attempt to “steer the development of a voluntary biodiversity credit market”. These biocredits are of course backed by WEF which considers these credits to be an “investment” in nature’s recovery. An analysis by IIED claims that biocredits can incentivise nature conservation and restoration to benefit marginalised groups living with nature, yet many critics consider this as yet another round of greenwashing. We’ll explore the pitfalls of biocredits later in this article.

How do we save nature that we have destroyed?

The simple answer is by protecting those systems that have yet to be damaged and helping to restore those that have already been damaged or destroyed. This is of course much easier said than done. Nature doesn’t demand a technological fix. It does well when given the opportunity, environment and resources to repair, restore and self-regulate. This natural propensity is often exploited by humans, with over 90% of the world’s forests regenerating naturally, albeit not with the same degree of biodiversity when left unmanaged by human hands or machines. Environmental regeneration requires a multi-pronged approach that includes education, self-regulation of various industries and targeted regulation that prevents industries or individuals incurring significant, especially irreparable, damage to natural and semi-natural, sustainable systems.

This means we must prioritise and invest our energies in nature and natural systems, without seeking a direct return on investment – the very thinking that has led to the environmental exploitation that has engendered our current environmental crisis. This means we shouldn’t turn what is a problem, in this case, the loss of biodiversity, into a business opportunity open to exploitation by the planet’s mega corporations and governments. It also doesn’t just mean paying lip service to biodiversity.

If we were serious about engaging with approaches that promoted biodiversity, we’d be prioritising getting as much of our food from sustainable, regenerative food systems as possible, we’d be focussing on the power of plants, fungi, microbes and other natural products in medicine, and we’d be drastically cutting back on our dependence on new-to-nature chemicals and electromagnetic radiation sources. In reality, society is moving the populous even further from this kind of close relationship with nature.

What we’re actually doing, as a technologically-based society, is incongruent with this approach. Technology is separating us ever more from our natural base.

“We are more than interdependent with the rest of life, we are inter-existent. What we do to Nature, we do to ourselves. That is the truth called interbeing. We will never escape that truth, no matter how far we retreat into our

virtual bubbles. […] The root crisis of our time is a crisis in belonging. It comes from the atrophy of our ecological and community relationships. Who am I?”

— Charles Eisenstein, extract from his ‘Transhumanism and the Metaverse’ substack (2022)

In reality, we continue to transition to ever more unnatural systems of agriculture, with gene editing of crops and animals, increased use of agrochemicals, and introducing fermentation systems and cell-based meats. These new human feeding technologies have no long term data to suggest they’re adequate let alone safe, yet they are being pushed as urgent solutions to the threat posed by climate change. Current investments in cell-based meat technologies is estimated to exceed £2.6 billion.

Does this fervour for technological fixes draw from the same playbook as the ‘covid-19 genetic vaccine that will save the world’? It seems so. Fortunately not all countries are prepared to ditch their livestock farming for cell-based meat: Italy looks ever more likely to become the first country to ban synthetic meat.

In medicine, the trend is similar, as the medical mainstream distances itself ever further from natural health while fostering a regulatory system that limits access and a restriction on free speech about natural therapies. We’re bombarding the world with ever greater amounts of anthropogenic EMFs with evidence of harm, affecting not just us but also the environment. Renewable energies, especially solar and wind, are being pushed, subsidised and incentivised without a clear understanding of the wider impacts of these on health, environment and sustainability.

As Eisenstein writes, “What we do to nature, we do to ourselves”.

A recent INTREPID report (now removed from its website, but available on the Wayback Machine) entitled “A Sustainable Future for Travel from Crisis to Transformation” suggests potential solutions to ‘climate change’ including virtual vacations. Tuvalu, a small pacific nation in Oceania, is set to become the first country to create a digital version of itself so that by 2040, we will no longer need to travel on vacation when we can do it from an armchair in our own homes. ‘Solutions’ like these only deepen our disconnection from nature.

The solution being offered

When a problem is presented by global think tanks and policy drivers like the WEF, chances are they have thought through a solution that benefits the globe’s biggest stakeholders. In the case of biodiversity loss, the solution being offered to the world comes in the form of biodiversity credits.

These are defined as “a legal document that represent the environmental action made, where it took place, who developed it, under what methodologies, and that has been certified following a specific system”. In the UK, they are regulated by the Environment Act 2021 which is a new framework for environmental protection that sets binding targets for air and water quality, biodiversity and waste reduction, establishing the Office for Environmental Protection as the new environmental watchdog. Part 6, Art 101 of the Act states that “a person who is entitled to carry out the development of any land may purchase a credit from the Secretary of State for the purpose of meeting the biodiversity gain objective”.

With an estimated financial investment of $711 billion annually needed to preserve and protect nature, these credits aim to ‘fill that gap’ by requiring individuals and firms to invest in environmental projects that aim to foster biodiversity. While biodiversity credit protagonists are keen to suggest that investing in biodiversity credits shouldn’t be confused with biodiversity offsetting, it’s hard to see how biodiversity credits won’t encourage a corporate interest to give, on one hand, the impression of its deep concern for our planetary and wildlife woes through its support of targeted, stakeholder-appproved biodiversity projects, while, on the other hand, it’s business as usual. That means doing what businesses have done for decades: pollute and decimate the environment. We have a name for this kind of trade off and it’s called greenwashing.

Will biodiversity credits truly feed into the actions needed to recover biodiversity losses and rebuild nature’s equilibrium?

Exactly how biodiversity credits will work remains unclear. With carbon credits, these can be quantified using metrics based around greenhouse gas equivalencies (CO2 equivalents). But biodiversity can’t be measured as easily or assessed using a limited clutch of metrics. A net positive biodiversity outcome — while being the objective — assumes some kind of universal currency or metric that has yet to be agreed, even by nature’s new corporate investors.

The WEF states a biodiversity credit system “should deliver measurable ecological outcomes and long-term certainty to investors and biodiversity custodians.” That’s a lot easier said than done.

You’ll appreciate the complexity of the task when you soak up the formal definition of biodiversity as proposed by the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), this being the legal instrument, ratified by 194 nations, that has been appointed as the ultimate custodian and arbiter for "the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources". The CBD defines biodiversity as follows: “the variability among living organisms from all sources, including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”.

The emergence of this biodiversity credit system appears ever more like yet another way of commodifying nature, creating a scarcity mindset, and creating opportunities for investors, in what Jeff Conant, writer and activist, calls “the continued enslavement of nature”. It is also another opportunity for companies to greenwash and boast about their ESG credentials.

Apart from the fact that the biodiversity credit system is currently being built by those who are set to gain from it, these credits focus ever more attention on technological ‘fixes’. Nature has no inherent requirement for technology – in fact, the majority of its sufferance comes from technology and exploitation by humans.

Nature, like the human body itself, has remarkable powers of self-healing if provided with the right environment, one that minimises interference by humans and our species’ technology. Let’s remind ourselves of the way wind farms and electric vehicles have been presented to the public as the ultimate renewable solution to fossil fuel scarcity and pollution – and now re-assess what environmental challenges wind turbines and battery technologies present to our planet (see here and here). The 17 UN Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) that are part of the centralised, UN-controlled mission towards social and environmental responsibility have actually been the driver of altogether new social and environmental problems linked to the quadrupling of demand for minerals (notably cobalt, nickel and lithium) used in battery technology, the processing of which is heavily centralised in China. The lesson we seem incapable of learning is a simple one: new technology, new set of problems.

Our desire to so often look to technology to solve problems that we have created, often through the use of new technologies, is part of the process that continues to separate us ever further from nature. Technology can play very little part in restoring wetlands, rebuilding the biological capacity of soils, or re-establishing rainforests or coral reefs. Biodiversity credits run the risk of creating new technological and economic systems, like decarbonisation technologies, that cannot guarantee the recovery of biodiversity. They will also provide new opportunities and markets for businesses keen to offset the harms they have induced on biodiversity or other aspects of the environment. As we said earlier: what they give with one hand, they will take with another.

Also don’t think that carbon and biodiversity credits are not linked: the plan seems to be to promote the stacking and bundling of carbon and biodiversity credits to the corporate sector. This will have the effect of diluting attention on the biodiversity crisis and the ongoing, human-induced sixth mass extinction. Not only that, it will be just what’s needed to keep everyone’s focus on the UN centralised, SDG control agenda and Net Zero plan.

What can we do?

The fate of our planet, and all the life forms with which we are inter-dependent, lies in our hands, hearts and minds.

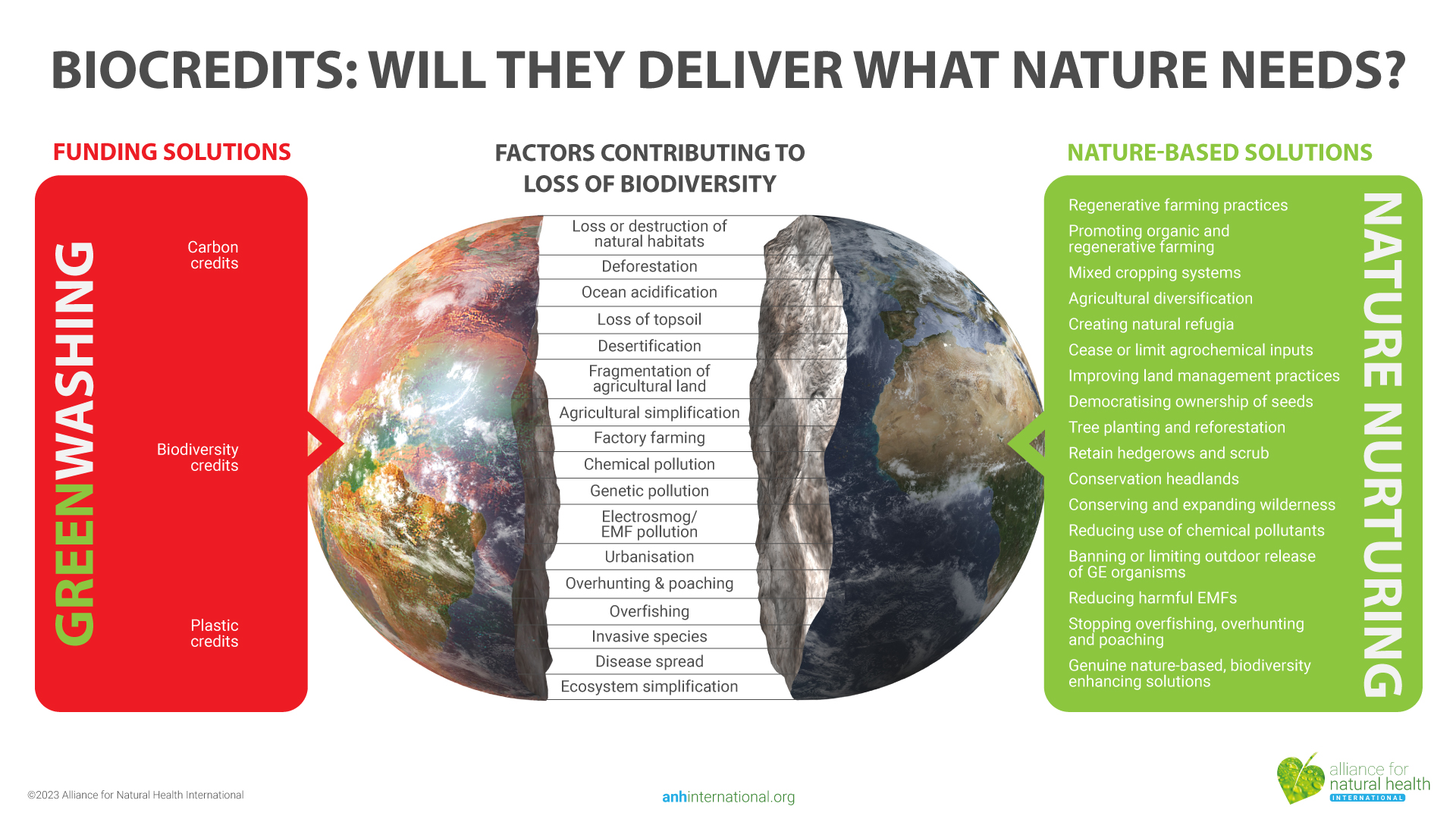

The right side of our infographic (above) offers 17 strategies (not SDGs!) that can help reverse biodiversity losses, these being listed below:

- Regenerative farming practices

- Promoting organic and regenerative farming

- Mixed cropping systems

- Agricultural diversification

- Creating natural refugia

- Cease or limit agrochemical inputs

- Improving land management practices

- Democratising ownership of seeds

- Tree planting and reforestation

- Retain hedgerows and scrub

- Conservation headlands

- Conserving and expanding wilderness

- Reducing use of chemical pollutants

- Banning or limiting outdoor release of GE organisms

- Reducing exposure to harmful EMFs

- Stopping overfishing, overhunting and poaching

- Genuine nature-based, biodiversity enhancing solutions (this is a catchall for the many other solutions not listed above)

In addition to supporting these approaches, there are some practical things that we can do as individuals, as well as collectively, in order to re-kindle our relationship with nature and be instrumental in allowing the regeneration of our land, air and waters, while minimising the damage incurred through our activities:

- Support local and regional environmental and regenerative agricultural initiatives

- Build biodiversity in our own communities by growing insect-friendly plants, planting native trees and shrubs, reducing food waste and shopping locally where possible

- Engage in citizen science projects that monitor biodiversity

- Support local conservation initiatives through financial or practical support, especially those where we know most funding goes directly to the conservation effort rather than being lost in a bureaucracy

- Bring pressure to bear on governments to put the health of the environment before the interests of the corporations, governments and global non-governmental organisations

- Reduce our food dependency on supermarkets which support industrial agriculture and buy instead from farmers markets, the ‘farm gate’ or organic box schemes that support local or regional regenerative farming

- Campaign against the use of agrochemicals and other environmental contaminants such as PFAS, and opt for organic, pesticide-free produce where possible

- Support research investigating the non-thermal effects on biological systems, as recommended by the Bioinitiative Report

- Join and support campaigns for a new rationale for safety standards applicable to technologies and devices that emit anthropogenic EMFs

- Share information to educate others on the impact of chemicals and anthropogenic EMFs on nature and the environment.

Ultimately the solution comes from us: what choices the majority of the people on the planet make. Sustained grassroots action is needed to avert the destruction being wrought by the corporatocracies that have assumed global control of the world. Much more incontrovertible than the climate change issue, the loss of biodiversity – this sixth mass extinction – represents not only one of the greatest threats to the viability of biological systems on our planet, it is also one of the most significant existential threats to our own species, at least in its current form.

Let’s help our troubled planet, and the trillions of beings with which we share this space and time, repair, rejuvenate and reinvigorate. Let’s also be hyper-aware of, and cautious of, the corporate greenwashing and environmental tokenism that will inevitably haunt the ongoing development of a global biodiversity credit system.

>>> If you’re not already signed up for the ANH International weekly newsletter, sign up for free now using the SUBSCRIBE button at the top of our website – or better still – become a Pathfinder member and join the ANH-Intl tribe to enjoy benefits unique to our members.

>> Feel free to republish - just follow our Alliance for Natural Health International Re-publishing Guidelines

>>> Return to ANH International homepage

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences