Content Sections

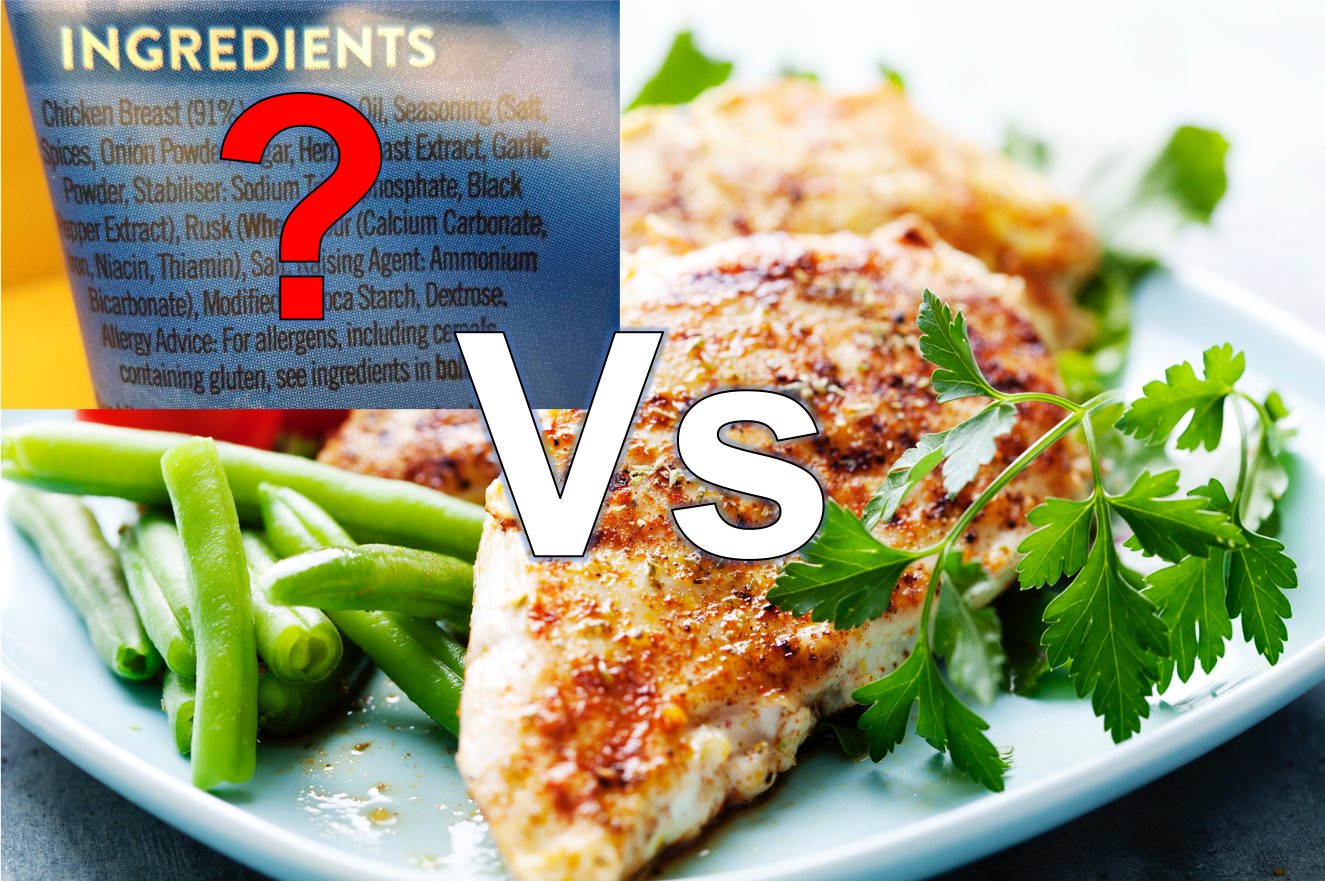

We, the public, increasingly don’t like ingredients lists on foods that look like a stocklist in a chemical factory. Survey after survey, whether in Europe or the USA, tell us this. You can see the changes on the supermarket shelves too. Heightened concerns over plastics has also generated a trend for plastic-free loose fruit and veg, with the UK’s Morrisons supermarket trialling plastic-free aisles in 60 of its stores and even Iceland, known for its frozen foods, is running trials.

But is the trend for food manufacturers to only list ingredients that the buying public recognises all good – at least for consumers? Are there loopholes that less scrupulous players can exploit? What are the implications for the food industry? Where might the trend lead?

Save the date: Clean Label 2019 webinar

These are all issues that will undoubtedly be picked up in the Clean Label 2019 webinar being organised by Food Navigator on 24th September, in which our founder, Rob Verkerk is participating as one of four experts along with Food Navigator journalist, Oliver Morrison.

If this subject whets your appetite, register for the free webinar now. If you missed it the webinar is now available on demand until 24 December 2019.

As a warm-up, let’s look to some of the issues that we think are important as this trend gathers steam, both good and bad.

Positive trends

There are some very powerful trends that are moving in parallel with ‘clean labelling’. These include stronger demand (and supply) of plant-based foods, especially vegan offerings. That’s being pushed along by global, scientific concerns about the sustainability of the food supply, not all of it being entirely scientifically rational.

Getting nasties or unknowns out of foods is par for the course with clean labelling. That means there’s a strong push to get rid of technological aids along with their corresponding E numbers, and replace them with known ingredients that replace at least some of those functions. For example, you’re more likely to see benzoate preservatives replaced with natural ones like ascorbic acid (vitamin C) or tocopherol (vitamin E). Synthetic nitrites and nitrates that have for so long been used to preserve processed meats sold in supermarkets, and likely contribute to their potential carcinogenicity, are rightly losing favour too. Alternatives include celery or chard powders that are rich in natural nitrates and naturally-cured products (yes, the way our great grandparents did it!).

Sustainability has definitely gone mainstream, with a strong push for sustainably produced foods, with ever higher requirements for transparency, as well as metrics that support the claims. Sustainability of course isn’t restricted just to reducing untoward environmental impacts, it also considers the two other pillars of sustainability, social and economic impacts. That interest drives ever greater demand for certification schemes like FairTrade and FairWild, as well as certifications like B Corp for ethical businesses.

While organic continues to grow, there is still a sense among some that organic foods are too expensive for those with tighter household budgets. This paves the way for increased demand for farming methods that not only don’t damage the environment, but actually enhance it. Pesticide-free foods and wildlife-friendly food products are two growing categories in this space.

There’s also a continued push for new, nutrient-dense ingredients – these may help to deliver a greater diversity of nutrients into modern populations that are suffering the ravages of the dietary simplification that has accompanied the globalisation of our food supply. Anyone for more seaweed, mushrooms – or even jackfruit?

Some concerns

If the clean labelling trend gets more people to get healthier, it’s got the thumbs up from us. But if all the hype around so-called clean labelled products makes people drift away from wholesome, unpackaged, natural foods and cooking from scratch, not so much.

No discussion is complete without at least a mention of meat analogues or alternatives, like the Impossible Burger, now available in Burger King’s in the US in the form of the Impossible Whopper, advertised as 100% Whopper, 0% beef. It’s journey to Europe given its reliance on heme made by GM yeast is not going to be so easy both from a regulatory and consumer acceptance point of view. So Burger King and its ilk are considering other options. If you’re into fast food outlets, and you want 100% plant-based, there’s the McVegan, made with Nestle's Incredible Burger that’s debuted in some McDonald's locations in Germany, Finland and Sweden.

But, in the case of the Impossible Burger and other foods made with cell-based technologies, could you really call these ‘meat analogues’ clean foods if they’re produced using GM tech and have no track record of long-term safety in our food supply? But could it be better for the environment? These are big questions that don’t have answers that are as straightforward as some might imagine.

There’s also the matter of the degree of food processing – something that’s important for those who continue to be reliant on manufactured food products, rather than on unpackaged, whole foods without barcodes. Highly processed foods may not only have an inferior nutritional profile and be deficient in health-generating compounds, the carbohydrates in them may be so mechanically or chemically processed they contribute to elevated blood sugar spikes and therefore diabetes and obesity risk. A Scottish study showed that people in urban areas are more reliant on highly processed foods. What about encouraging the food industry to use the NOVA classification system for the degree of food processing?

A loophole that concerns us at ANH is around what constitutes ‘natural’, that has limited definitions certainly in EU food law, linked to very specific products, notably mineral waters. If you see a product with “Natural Flavours Vanilla” on the label, think again if you thought this flavour originated from a vanilla pod, let alone from Madagascar! Cloves provide a plentiful supply of vanillin, the main compound responsible for vanilla’s flavour, but equally, it could also be a nature-identical form of vanillin produced in a chemical factory. Not exactly what the average health and environmentally conscious consumer might think.

Then there’s the chemicals that have been added to ‘free from’ foods like xanthan gum, that continues to be linked to digestive complaints, a characteristic that has been long known. Increasing plant food intakes may also lead to increased exposure to anti-nutritional factors such as lectins that can be particularly abundant in certain foods, such as legumes, that the likes of Dr Stephen Gundry have consistently suggested may seriously interfere with long-term health.

What about provenance? We all like to know where our food comes from, right? Well, for multi-ingredient foods, the country of origin marked on the label tells you where the food was made, but it tells you nothing about from where all the ingredients in it are sourced? Time for more transparency and traceability? Therein lies another major plus for organic certification.

A final point worth considering is the order of ingredients, even on a supposed ‘clean food’ label. Labelling laws require that ingredients are listed in descending order of weight. If a manufacturer doesn’t tell you how much of each ingredient, how do you really know anything about its overall micronutritional profile (macronutrients will of course be listed on the Nutrition Information panel)?

Want to find out more?

- If you want to delve in more to this fast-changing subject, sign up for the online Food Navigator webinar on 24 September (If you missed it the webinar is now available on demand until 24 December 2019)

- Learn about ANH’s Food4Health campaign

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences