Content Sections

Since, according to our governments, we’re all meant to be tightening our belts in the collective interests of society, where does healthcare fit into the picture? According to new research, natural and integrated medicine have important roles to play in reducing bloated national healthcare budgets.

Huge costs of healthcare

Thanks to global economic turmoil, citizens are being asked, or rather coerced, into stiff ‘austerity’ measures by their supposedly cash-strapped governments. Predictable results have ensued. However, healthcare costs remain as high as ever. For example, in 2010, the USA spent 17.9% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare; from a GDP of $13.24 trillion, that’s around $2,369,960,000,000 or $8,362 per US citizen. France, which has one of the best healthcare systems in the world, spent 11.9% of its $2.56 trillion GDP on healthcare in the same year: $304,640,000,000 or $3,130 per citizen. However that money is spent, and whether managed by government, the private sector or citizens themselves, those are enormous figures. Any serious assault on state spending must take healthcare into account, so can non-mainstream healthcare modalities – many of which are focused on disease prevention, and can be expected to reduce healthcare service utilisation – contribute to cutting healthcare budgets?

Systematic review of CAM cost-effectiveness

New research indicates that they can. Researchers including Professor Claudia Witt of Berlin’s Charité University have taken the most comprehensive look yet at the economic performance of what they term complementary and integrative medicine (CIM), and identified several clinical areas where money could be saved by using CIM alongside standard medical care.

The authors point out that previous studies with similar goals to their own contained significant flaws, most notably inadequate search strategies that failed to locate all, or even the majority, of economic evaluations of CIM. Their solution, which expanded on a definition chosen by the Cochrane Collaboration, searched six electronic databases and employed 50 search terms, identified 338 economic evaluations of CIM – utterly eclipsing previous efforts, which identified between 34 and 56 such evaluations. The authors classified 114 of these as ‘full economic evaluations’, meaning that they, “Compared the costs (inputs) and consequences (economic, clinical and/or humanistic outcomes) of two or more therapeutic alternatives applied to the same patient population”.

Cost savings identified

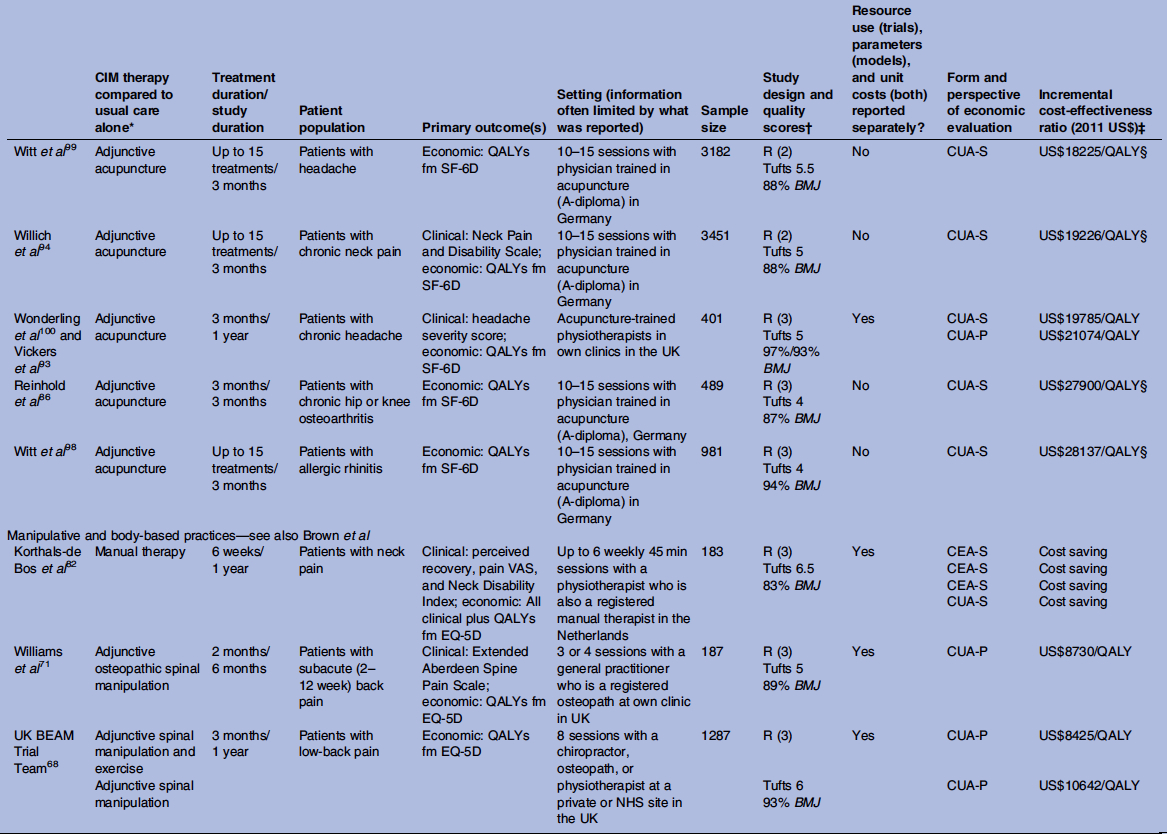

Importantly, the results of 22 of the 31 highest-quality studies identified by the authors could be applied to clinical settings beyond those used in each individual study – a property known as ‘generalisability’. The 31 high-quality studies included a total of 56 comparisons between usual medical care and CIM – and, of these, 16 (29%) showed that additional CIM therapy had better health outcomes and lower costs than usual care alone. Specifically, cost savings were observed for acupuncture both alone and in combination, manual therapy, various forms of dietary supplementation, tai chi and naturopathic care. Some sample results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. A sample of the results of economic evaluations of CIM (taken from Herman PM et al. BMJ Open 2012;2: e001046).

Conclusions

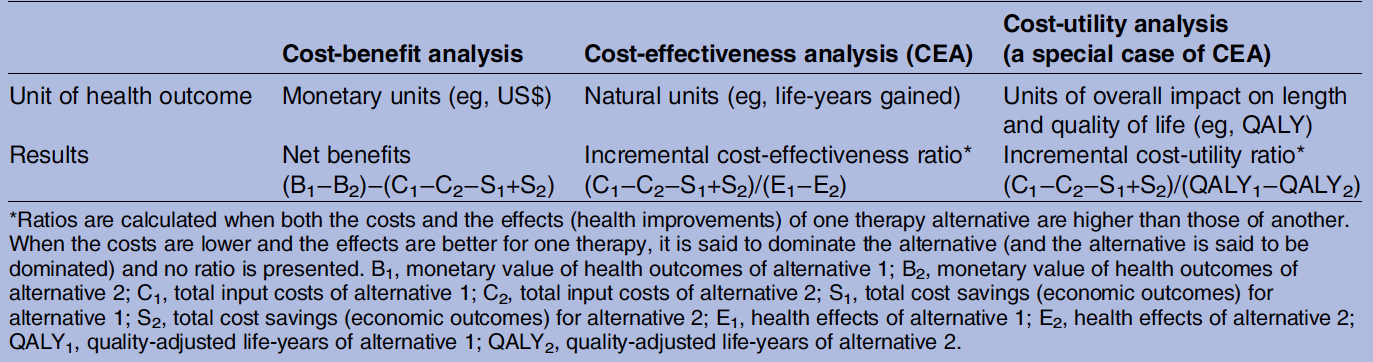

These are encouraging results not just for natural and integrated medicine, but for society as a whole. Not only did CIM provide cost savings in nearly 30% of high-quality comparisons with standard care, but the same was also true for 18% of cost-utility analyses (CUAs) – the most rigorous form of cost assessment (Table 2).

Table 2. Types of full economic evaluation CIM (taken from Herman PM et al. BMJ Open 2012;2: e001046).

Compare this with a 9% cost-saving figure obtained in a review of 1,433 CUAs across all medicine, and it’s clear that increasing the everyday use of natural and integrated medicine has the potential to reduce pressure on overloaded health budgets. And because of the high degree of generalisability of the studies in question, the cost-saving potential of these modalities should be considered in other settings.

The authors make several recommendations for future work, most pertinently that future studies must consider that most patients use more than one CIM modality. It will be interesting to see whether use of multiple modalities increases the cost savings above those achieved with single therapies. In fact, the greatest cost savings associated with CIM may be related to its preventive capability – since regular users may be far less likely to require the services of national health systems – and urgent research should be performed in this direction as well. Researchers must prioritise the development and implementation of high-quality economic evaluations into a greater range of non-mainstream healthcare modalities; there is not a single high-quality study of the economic benefits of any herbal interventions, for example. But for now, we hope that policymakers worldwide will take heed of these results by making natural and integrated modalities more widely accessible in their national health programmes.

Comments

your voice counts

05 December 2012 at 10:12 pm

I am attempting to interest the NHS (UK) in saving about £30 billion on treating type 2 diabetes with diet "only" because it is well known that treating this condition with insulin is criminally negligent.

Yet, the person responsible in this government agency is so trained by the pharmaceutical industry, that she is trying to wear me down, in the hope that I will get frustrated and giver up.

What a shambles this is. The Chancellor is desperate to save money as the country faces a massive debt which they are finding very difficult to pay off, but will not go against the pharmaceutical industry and stop the incompetent treatment of type 2 diabetics with insulin.

I don't wonder why the average citizen is hosed off with politicians - DO YOU ?

06 December 2012 at 12:42 am

Has lack of any pharmaceutical substance ever been proven with the gold standard of research? No. Yet hundreds of thousands of people who are suffering signs of chronic nutrient deficiency are treated as if suffering from PPD ( petroleum product deficiency ) every day. To bring a metabolism that is sending out an SOS back to homeostasis with the help of fresh juices and nutrients would lift the burden of health care costs substantially. But this would mean falling stocks and we are led to believe this eqals the end of time. That's why the high priests of health care go on treating people like lube requiring machinery.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences