The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has finally bowed to the inevitable: neonicotinoid pesticides are, it says, contributing to the bee deaths attributed to colony collapse disorder (CCD). But its proposed restrictions aren’t the end of the story.

Busy bees

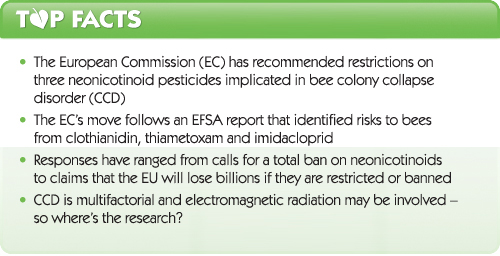

2013 has already been a busy year for bees – European Union (EU) bees, at least. On 31st January, the European Commission (EC) presented a proposal to EU Member States that will, if adopted, significantly limit the use of three neonicotinoid pesticides strongly suspected of being involved in bee colony collapse disorder (CCD). If implemented, the EC’s proposals will not only restrict clothianidin, thiametoxam and imidacloprid to crops that don’t attract bees and winter cereals, but also ban outright the sale and use of seeds treated with ‘plant protection compounds’ containing these pesticides.

How did we get here?

The EC’s move, described as, “Ambitious but proportionate” by recently appointed Commissioner Tonio Borg, can be traced back to two papers published in the journal Science in 2012, authored by Mickaël Henry et al and Penelope R Whitehorn et al. The research reported in the papers indicated that certain neonicotinoid pesticides had adverse effects on bumblebee foraging success, survival and reproduction, which was alarming enough for the EC to request a scientific statement from EFSA.

EFSA duly obliged on 30th May 2012; its statement confirmed that the pesticide doses used in the Science studies were broadly in line with estimated actual exposures in bees. Following a further EC request, EFSA performed a risk assessment that identified “A number of risks posed to bees by three neonicotinoid insecticides,” namely clothianidin, thiametoxam and imidacloprid.

Predictable responses

Clearly forewarned, the European pesticide industry released its own report on 15th January, the day before EFSA’s risk assessment was published, claiming that, if neonicotinoids were banned or suspended, “Over a 5-year period, the EU could lose €17 billion or more and over 60,000 jobs...”. Representing the other side of the argument, one with which we also concur, Greenpeace and Pesticide Action Network (PAN) Europe urged the Commission to go further and order a full ban. The Green group in the European Parliament joined the call for a ban, pointing to yet another report – this time by the European Environment Agency (EEA) – that concluded, “Imidacloprid seems to be a substance particularly 'fit for the precautionary principle'”.

Is that a bee in the room? No it's an elephant

We fully support any moves that will reduce the amount of pesticides released into the environment, especially if they are damaging to bee health. But the problem with complex issues such as bee decline is the sheer number of factors, many of which may interact with one another, that may operate simultaneously. Factors that may have an influence include weakening genetics and immune response of 'domesticated' bees, pressure from pathogens (disease-causing organisms), climate change, genetically modified organisms—and lest we forget—the possible role of electromagnetic radiation (EMR) from modern, wireless communication devices such as mobile phones. No-one appears to be investigating the effects of electromagnetic radiation (EMR) on bees’ health or navigational abilities.

Time for a paradigm shift in research

EFSA, like most health authorities, seems to be confident that it's found a way of teasing out individual factors that might be harmful or beneficial to either humans or the enviroment. But the evidence needs to be staring them in the face for them to see these effects. That works well with products like pesticides that are overtly toxic to organisms like bees that are very susceptible, but it works less well for more complex interactions such as those associated with GMOs. It also doesn't work well when you are investigating a possible beneficial effect of a food constituent in amongst something as diverse and varied as the human diet. Through the EFSA lens, it's therefore not a great surprise to find the single 'highest food authority in Europe' declaring that GMOs are safe and that most foods and food constituents are not beneficial to human beings.

It's just possible that the decline of bees and the groundbreaking ecological work undertaken by ecologists with specific interests in complex interactions between insects, pathogens, plants and changing environments could be the ticket to evolving more appropriate methods of scientific research for these complex systems.

Comments

your voice counts

07 February 2013 at 5:30 pm

It's a pity we can't go back to the old ways, instead of fighting nature, start to work with it. Allow so called weeds to grow in with the crops and harvest crops by hand.

09 February 2013 at 4:19 pm

I`m in total disbelief that an individual or company could object to the banning of chemicals causing bee colony collapse. Considering the consequences of bee extinction is frightening. This is real psychopathic insanity for the sake of a few bucks.

11 February 2013 at 3:10 pm

Sure, spend time squabbling about who will lose money, while the rest of the bees die. Can we do ANYTHING as a species that is NOT purely money motivated?

16 June 2014 at 7:04 pm

There's definitely been more media attention brought to the alarming rate of the declining bee population. Unfortunately big corps won't do anything as long as the $ rolls in.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences