By Robert Verkerk PhD Executive and scientific director, ANH-Intl

A husband and wife pairing, both psychoanalysts, were among the first Westerners to tell doctors, initially in the UK, that the effect of any drug would pale into insignificance when compared to the effect of a good doctor. Michael and Enid Balint (pronounced Bah-lint, given Michael originally hailed from Hungary) started researching the doctor-patient relationship in the 1950s. In 1957, Michael Balint published a book that still remains on the general reading list of UK general practitioners. Unfortunately, we’ve found that some medical students are encouraged not to read it. One notable irony is that the book is even more relevant today than it was when it was first published.

In his book, Balint, who passed away in 1970, tells his readers:

“By far the most frequent drug used in general practice was the doctor himself. It was not the bottle of medicine or the box of pills that mattered but the way the doctor gave them to his patient.”

Fortunately, the Balint Society in the UK, and the International Balint Federation, remain in homage to Michael and Enid Balint’s mission. These organisations work to directly help doctors, usually via small groups, to better understand how they can in turn help their patients. They also help to coordinate research, especially on the emotional aspects of the doctor-patient relationship.

A variety of researchers and doctors have picked up the pieces to better understand the doctor-patient relationship since the Balint era.

Dave Rakel and Ted Kaptchuk

Among these is Dr David Rakel, who began his medical career working as a rural family practice physician out of his hometown in Driggs, Idaho, USA. His daily practice involved delivering womb-to-tomb medicine, dealing with conditions as varied as lacerated limbs caused by agricultural machinery through to chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer and Alzheimer’s. Dave Rakel soon began to realise that his main weapon against disease — pharmaceuticals — was not delivering the best outcomes for his patients.

Many practitioners already using non-conventional methods will know David Rakel as co-author, along with his father (Robert), of Integrative Medicine, now in its second edition. It’s one of the classic textbooks on the subject, and it’s intended to empower both the clinician and the patient. In the video, Rakel somewhat mischievously asserts that the ultimate purpose of the book is to put clinicians out of business!

Drs Rakel, father and son, talk about their latest edition of Integrative Medicine (now available in electronic and print form)

However, readers may be less familiar with Rakel’s research, some of which has been funded by none other than the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

From his current position as Director of the University of Wisconsin (UW) Integrative Medicine faculty, Dr Rakel demonstrates that the way we see the world, how we carry ourselves, our emotional state, our social connection within our communities, and our movement and exercise are among the key factors that influence self-healing: the most powerful influence on any disease.

If you'd like to understand more about what you can do to improve your health using fewer drugs or supplements, we suggest you consider trading an episode of your favourite TV programme for a one-hour lecture by Dr Rakel. Apart from the fact that you might well get an overwhelming sense to say to yourself, “I wish he was my doctor!”, there are numerous ‘pearls’ within his lecture that can easily be incorporated into your everyday life.

Dr Rakel lecture (2008): The Science of Perception: How We See the World Can Make Us Healthy or Sick!

The role of empathy

Dave Rakel and others have established that empathy offered by the practitioner is a key factor in self-healing. For example, the immune response following infection by the common cold is significantly reduced if a patient experiences a strongly empathic practitioner.

Another significant researcher on the subject is Dr Ted Kaptchuk, of Harvard Medical School. He’s particularly well known for his work on deconstructing the placebo effect.

Kaptchuk, and members of his group at Harvard, have undertaken many studies, the sum of which points to the non-specific factors around a given intervention often being considerably more important than the intervention itself.

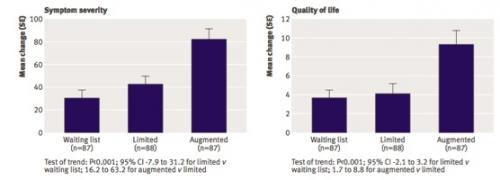

In one study, Kaptchuk and his team found a 62% improvement in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms during interactions in which sham (fake) acupuncture was delivered alongside ‘augmented’ clinical visits with the practitioner. These visits allowed time for the practitioner to focus on bringing warmth, attention and confidence to the interaction, as well as applying ‘dummy’ acupuncture needles. It’s worth noting that this practice in itself has been criticised. ‘Limited’ visits, consisting of sham acupuncture and limited practitioner interaction, yielded a considerably lower 44% reduction in symptoms. Patients under observation on a waiting list (the ‘control’ group) improved symptoms by just 28% over the 6-week ‘cross-over’ trial.

As pictures are worth a thousand words, following are some of the graphs from the study, showing the clinician effect as clear as can be. Put simply, more quality time spent with the patient — in other words, more empathy — equates to both reduced symptoms and improved quality of life.

Some findings from Kaptchuk et al’s IBS study published in the British Medical Journal in 2008

Ted Kaptchuk discusses the placebo effect for MIT Media Lab

So – is empathy being taught in medical schools?

The answer is generally: No! And neither is the science about empathy and its key role often taught. Even more disturbing, it emerges that empathy is actually ‘taught out’ of medical students over the duration of their training.

Bruce Newton PhD, Professor of Neurobiology and Developmental Sciences and Educational Development at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and colleagues published an important study of this in 2008. Not only did the authors find that empathy among medical students declined, especially after the first and third years, but students with differing empathic tendencies also selected quite different specialisms.

Bottom line

It’s a strange old world. We’ve known for years that the role of the practitioner is very important, in many cases more important than the treatment itself, and we now even have scientific proof.

Yet, not only do our medical students get taught little or nothing about it during their time at medical school, we also find that any empathic qualities that they might possess during Fresher’s week appear to be largely beaten out of them by the time they graduate.

We have truly become over-reliant on technological fixes —and until we start to appreciate the complexity of self-healing mechanisms and their interaction with key influences in the surrounding environment, optimised healthcare, as opposed to disease management, will be held back.

Voltaire, echoing in his typically satirical manner what has been known in traditional systems of medicine for millennia, probably said it best when he wrote, “It is the physician’s job to amuse the patient while nature cures the disease.”

Comments

your voice counts

18 July 2013 at 4:42 am

This is indeed true. Some patients do not really want to take any medications due to the undesirable side effects. This holds true especially to those who are experiencing psychological crises. The human intervention of counselling was found out to be more effective than therapeutic medications.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences