In its own words, the European Union’s (EU’s) Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation (NHCR; No. 1924/2006) is designed to ensure a, “High level of consumer protection” (Article 1.1). But approving an unscientific health claim for fructose, as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) did recently, protects nothing but Big Food’s profits. And, by ushering in an inevitable flood of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) products with ‘healthy’ labels, EFSA’s decision is a clear danger to public health.

Fructose under the radar

It attracted little attention at the time, but European Commission Regulation No. 536/2013, published in the Official Journal of the European Union in June 2013, could have enormous repercussions.

Following an EFSA opinion that dates back to 2011, Regulation No. 536/2013 authorises a health claim for fructose. If the manufacturer replaces 30% or more of the glucose or sucrose in its product with fructose, it can place a health claim on the product stating that it reduces blood-sugar spikes after eating.

What’s the problem?

It would be difficult not to see Big Food’s fingerprints all over this decision. The inevitable consequence will be a flood of high-fructose products appearing on the EU market, all proudly proclaiming their health benefits. And if the term ‘high fructose’ rings a bell or sends chills down your spine, there’s good reason – high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is wreaking havoc with the health of the US public in several ways:

- According to US Department of Agriculture figures, US citizens have vastly increased their HFCS intake since the 1970s, after the beverage companies in particular switched to a sweetener based on highly abundant corn. Notably, this period saw skyrocketing US rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes

- HFCS is implicated in the increased incidence of both obesity and type 2 diabetes

- HFCS is frequently contaminated with mercury and other, unknown, substances

- Since nearly 90% of US corn is genetically modified (GM), HFCS derived from it is highly likely to contain GM material. This presents numerous associated health risks.

How fructose affects your body

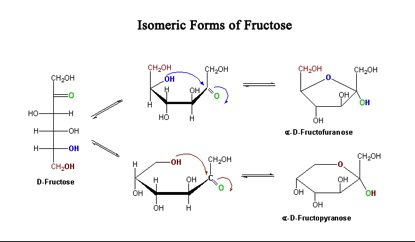

Fructose is a so-called ‘simple’ sugar, or monosaccharide, consisting of molecules containing six carbon atoms. Fructose is an alternative molecular form, or isomer, of glucose (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The isomeric forms of fructose.

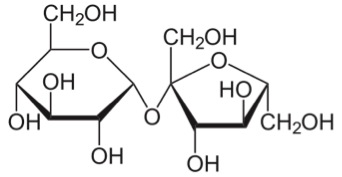

Sucrose, or standard cane sugar, is a disaccharide consisting of one molecule of fructose and one molecule of glucose (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The molecular structure of sucrose.

The obvious differences in molecular structure between sucrose and fructose explain their differing biochemistry:

- Free fructose does not directly stimulate the insulin response, although intriguing research in mice suggests the existence of an indirect mechanism. Insulin release is normally triggered by the ingestion of glucose, and prompts cells to absorb glucose so that it can be utilised as an energy source

- Fructose is easily metabolised to fat: Fructose is taken into cells via an insulin-independent mechanism, where it is eventually metabolised to phospholipids, triacylglycerols and fatty acids. Both triacylglycerols and fatty acids are fat precursors. Furthermore, fructose metabolism in the liver favours lipogenesis (fat production)

- Fructose-rich diets cause insulin resistance, impairing cholesterol homeostasis and increasing the risk of metabolic syndrome or ‘syndrome X’

- Fructose increases serum uric acid levels, resulting in an elevated risk of gout in men

- Fructose has similar bodily effects to alcohol, including liver toxicity and addiction

- Fructose may produce less feelings of satiety and fullness compared with glucose, possibly through contrasting patterns of cerebral blood flow stimulation

- Fructose may affect satiety via other mechanisms, such as leptin resistance.

Specific problems with HFCS

Glucose and fructose occur in a 50:50 ratio in sucrose and are tightly bound together via a glycosidic chemical bond. In HFCS, glucose and fructose exist in different ratios according to the intended application, with fructose present in proportions ranging from 42% to 90%. However, glucose and fructose are not chemically bound in HFCS – meaning they are absorbed more rapidly into the bloodstream. Not only does this cause insulin levels to spike following HFCS consumption, but research by Dr Bruce Ames has shown that absorption of free fructose from HFCS requires the gut lining to utilise extra molecules of ATP, the body’s primary fuel source. This eventually reduces the integrity of gut lining and causes ‘leaky gut’, the ultimate source of many chronic and autoimmune conditions.

The evolutionary perspective

On balance, the current and emerging evidence indicates that overconsumption of fructose – especially free fructose in the form of high quantities of HFCS – is a health disaster. This impression is compounded by the fact that humans possess multiple metabolic pathways to utilise glucose, while comparatively few exist for fructose. From an evolutionary perspective, in our ancestral past, we would indeed have eaten fructose – but only in small amounts and at specific times, when we came across fruit-bearing plants at the appropriate season for them to carry ripe fruit.

Of course, the fruits themselves – the ‘fructose carriers’ – have an important part to play in maintaining our health and vitality. Obtaining a limited amount of fructose by eating fruits is an entirely different matter to, say, drinking a can of soft drink loaded with HFCS. Not only is fructose absorption buffered by the fibre also present in the fruit, but the fruit’s enormous variety of co-existing phytonutrients, vitamins and minerals help the body to use the fructose appropriately. By comparison with eating fruit, drinking a can of fizzy pop is like landing a military jet on an aircraft carrier at sea, entirely alone, without the help of the hundreds of support staff normally on hand: highly liable to end in tears.

EFSA keeping its friends happy

All of which brings us back full circle as regards EFSA’s approval of a health claim for fructose. Experts have already lined up to condemn the decision. One of these experts, Prof Robert Lustig, blasted EFSA’s reasoning before coming to an unequivocal conclusion: “It is clear that this recommendation is scientifically bogus. Nutritional policy should be based on science – not pseudoscience”.

It’s hard to disagree. EFSA dismissed the evidence cited in its scientific opinion that fructose, “Induce[s] dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance and increased visceral adiposity in healthy and in hyperinsulinaemic insulin-resistant subjects,” by pointing to a single paper on glycaemic index (GI) dating from 2006. As Prof Lustig explains, GI is largely irrelevant when discussing fructose. Even more conveniently for Big Food, EFSA considered a tiny fraction – 11 references – of the available literature on fructose metabolism.

Rising to the challenge?

We believe, if there was the will and the necessary funds, that there are sufficient grounds to challenge this decision legally. Recital 22 of the NHCR states clearly that, “Health claims should only be authorised for use in the Community after a scientific assessment of the highest possible standard.” We’d be delighted to speak with any individuals or companies who might wish to entertain such a challenge.

And are we alone in noting a discrepancy between approval of the fructose health claim and the European Parliament’s recent rejection of a carbohydrate-related health claim over fears of increased sugar consumption? It seems that there is a desire from certain Big Food players to try to get EU citizens to consume ever increasing amounts of fructose in processed foods, especially in the form of HFCS. And it would be an odd twist of this were to happen while our US counterparts actually begin to cut down their consumption. Was that the idea all along?

Public education is everything – so we are relying on your help, dear reader, to share this story as widely as you can.

ANH-Europe Food4Health campaign page

Comments

your voice counts

23 October 2013 at 10:43 pm

"life-style" disease = fructose disease

This is going to be the major medical paradigm shift of the 21st century.

Fructose is found in sucrose (table sugar, 50% fructose), High Fructose Corn Syrup (55-90% fructose), and as free fructose mainly in fruit juices.

Fructose is the only molecule whose consumption rose by 6000% since 1700.

It is the single common thread that connects the dots of all the "life-style" diseases.

If you know of any "life-style" disease without a biochemically causal link to fructose, let me know. There is none.

I do not consider lung and skin cancer as systemic life-style diseases, as they are based on the more specific habits of smoking and sun-bathing.

However, based on the research by Dr. Cantley, I do consider all cancers of insulin-regulated cells as life-style diseases. This includes e.g. prostate, pancreatic and breast cancer.

And I surely consider obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis and related cardiovascular diseases, ADHD, Alzheimer, Parkinson, rheumaoid arthritis and probably multiple sclerosis as life-style diseases. That is, as *fructose diseases*.

This is why the EU "health claim" for fructose is really a health claim for the devil.

24 October 2013 at 5:54 pm

Since humans possess the digestive enzyme sucrase - every time sucrose in ingested it is broken down into glucose and fructose molecules - thus freeing the fructose molecules. Yes, HFCS should be avoided since it is a more concentrated source of fructose, but sucrose should be avoided as well.

26 October 2013 at 2:47 pm

Yes, be very careful everyone of high fructose. I was buying what I thought was a fairly natural strawberry flavoured yoghourt, until I started noticing it was giving me heartburn, after I had eaten it before bedtime. All the ingredients looked fine and I noticed the high fructose, not realising how nasty it was. After buying the yoghourt a second time and having the same reaction, almost being sick after eating it, I realised it must be the high fructose. I researched and found it must be the culprit.

Since this ingredient is probably present in a myriad of different foods and drinks, it pays more than ever to check out all ingredients on the label.

Needless to say, I no longer buy that yoghourt and find it is better to buy a healthy natural plain yoghourt and add your own fruit or a top quality (home made if possible) strawberry or raspberry jam to it. This is a much more delicious and nutritious fruit yoghourt, very simple to make.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences