Last week, 107 St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) products were pulled from online retailer, Amazon UK. The justifications given included use of unauthorised medicinal claims, unauthorised health claims and suggestions that the products may be damaging to consumers’ health.

However, it has become clear that in many instances, none of these justifications apply. There appear to be other drivers motivating the bust, these working directly against public freedom of choice for herbal food supplements with long histories of safe use.

The drive to remove the products appears to be largely a protectionist measure, protecting UK-based companies that have licensed herbal products as herbal medicines under the EU’s traditional herbal registration (THR) scheme. It also drives a coach and horses through the principle, supported widely elsewhere in Europe — including by the European Commission itself — of a liberalised ‘dual regime’ for THRs and herbal food supplements, in which both categories of products co-exist, side by side, in the EU marketplace.

The UK medicines regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), justified its approach saying, “We continue to warn people that herbal medicines not certified with a THR (Traditional Herbal Registration) logo and purchased from websites, particularly websites based overseas, cannot be guaranteed to meet standards of safe herbal medicines.”

St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum); the latest target of UK medicines regulators

Online trade news portal Nutraingredients broke the story on 5th March. A follow-up story on 9th March reflected the contrasting views presented by ANH’s Rob Verkerk and Schwabe’s Dick Middleton. The latter, also chair of the British Herbal Medicine Association, is one of the strongest proponents of the THR scheme free of competition from herbal food supplements based on the same herbal species.

In correspondence between Nutraingredients, the Health Food Manufacturers Association, and ANH, it is clear that some of the products have been wrongly considered as illegal based on claims. Of a list of four examples of supposedly “unauthorised medicinal claims on the products labels”, half could not be regarded as medicinal claims. Specifically, the mood enhancement claims, such as “to maintain a healthy emotional outlook” and “helps support a positive mental outlook” cannot, in our view, be considered as medicinal by presentation according to the definition laid down in EU medicines law. Such mood enhancement claims are in fact carefully worded health claims that are as yet not non-authorised by the European Commission or most national food regulators. Products forced off the market included those from leading US dietary supplement manufacturers Nature’s Way and Source Naturals.

Food medicine borderline

In the EU, the borderline between what is considered a food or food supplement, and what is a medicine, has long been somewhat opaque legally, although this is offset to quite a large extent by case law precedents set by the European Court of Justice (see below).

Food supplements are defined under the EU Food Supplements Directive (2002/46/EC) as “and which are concentrated sources of nutrients or other substances with a nutritional or physiological effect….”.

By contrast, there are two limbs to the definition of medicinal products under EU law (Directive 2001/83/EC, as amended). The first limb, often referred to as the ‘presentation limb’, classifies as a medicine, “Any substance or combination of substance presented as having properties for treating or preventing disease in human beings.” This is the limb that makes any claim suggesting a therapeutic treatment or disease prevention claim as medicinal. Such claims are therefore absolutely off limits for food supplements sold in the EU. It is this presentation limb, in the case of some of the St John’s wort products forced off Amazon UK, that appears not to have been transgressed, hence our grave concerns about the MHRA, and the HFMA, over-stepping the legal mark.

The second limb of the medicines definition, often referred to as the ‘functional limb’, has such a broad scope that it is technically breached by all foods and food supplements. It reads as follows, “Any substance or combination of substances which may be used in or administered to human beings either with a view to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action, or to making a medical diagnosis.”

This broad scope of definition is not unusual in EU law if there is a strong consumer protection concern, as there is with pharmaceuticals. The EU medicines law regime was first instigated in 1965 after the thalidomide tragedy and since this time it has been tweaked several times. It is the 2004 revision which extended the type of action from merely a pharmacological one, to ones including immunological or metabolic actions, the functional limb was broadened dramatically. This definition effectively hands regulators a ‘loaded gun’ to treat any food or food supplement product as a medicine—arbitrarily.

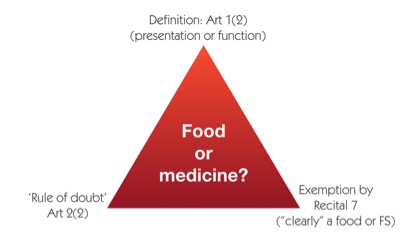

The limiting provision is given in the seventh recital (preamble) to the medicines directive (Fig. 1). It proposes that foods, food supplements, cosmetics and medical devices that are “clearly” such, should not be considered as medicines. However, the ‘rule of doubt’ also applies (Article 2.2), suggesting that where there in cases of doubt as to in which category a product should be classified, it should be regarded as medicinal. We sometimes think of this provision as the ‘medicinal supremacy’ clause in EU law.

Fig. 1. Legal mechanisms in EU law determining food or medicinal classification

Given the incredibly broad scope of EU medicines law, the European Court of Justice, as the highest legal authority on how national regulators should act, has provided clarification via numerous judgments.

Based on interpretation of relevant European case law, industry consensus guidance published in 2006 in the Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism (Coppert et al, Ann Nutr Metab 2006; 50: 538–554), mutual recognition provisions and recent work of the EU-funded PlantLIBRA project, the MHRA’s actions against many of the St John’s work products, cannot be justified.

Endangering consumers?

St John’s wort has an extremely good safety record, even by the standards of Edzard Ernst. It is a European native plant and has a very long history of use as a tea prepared from the leaves and flowering tops to enhance mood and support good quality sleep. The rich polyphenol content of extracts mean they have high antioxidant potential and liver protective effects at recommended levels of food supplement usage (typically around 300 mg extract including up to 700 mcg hypericin a day). However, very high levels of intake, and for extended periods of time, may be associated with side effects including liver damage, especially when associated with alcohol and drug abuse.

St John's wort’s primary action is by inhibiting serotonin uptake by acting as a mild monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MOAI). Therefore, according to commonly accepted practices, it is appropriate that warnings are included on labels. These include avoiding use in sensitive groups (e.g. pregnant women), highlighting risks of contraindications with other medications such as MOAIs and selective serotonin reuptake inihibitor (SSRI) antidepressants where these are appropriate, ensure dosages are not exceeded, and that products are only for short-term use.

However, the MAOI activity in St. John's Wort, in usual doses, especially those associated with food supplements, is not sufficient to trigger negative interactions with tyramine containing foods such as red wine and cheese.

EFSA has determined that the highest intakes consumed in herbal teas based on St John’s wort in the Netherlands may be around 1500 mcg hypericin/day, although typically the dosages would be around half this amount.

ANH therefore strongly supports the continued availability of St John’s wort as a food supplement on the basis that medicinal claims are not made, that quality controls are in line with good manufacturing practices for foods, that hypericin and/or hyperforin levels are determined (and hypericin does not exceed 1500 mcg/day), and that appropriate warnings are carried on labels and associated marketing.

Such products are proven to be many times less dangerous than SSRI and MAOI drugs, and help large numbers of people to maintain healthy emotional states without the requirements for medicines.

Mood enhancement vs treatment of depression

The primary intended use for St John’s wort food supplements has been to support the maintenance of positive emotional mood states. Such an intended use must be differentiated from products used specifically for treatment of clinical depression that is the sole domain of licensed medicines.

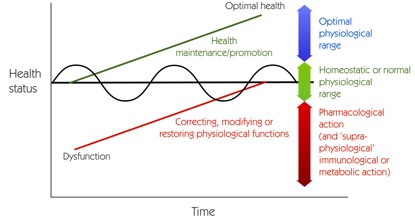

Key to understanding what is and isn’t viewed as medicinal by virtue of a pharmacological action, is a recognition that there are always fluctuations in health status, even when associated with normal, healthy physiology (Fig 2). This is after all the basis of homeostasis. The European Food Safety Authority has established such a precedent by accepting that people with specific conditions may represent appropriate study groups for scientific studies aiming to substantiate health, as opposed to medicinal, claims. EFSA’s 2011 guidance on the scientific requirements for health claims related to gut and immune function, states, “Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) patients or subgroups of IBS patients with constipation are generally considered an appropriate study group to substantiate claims on bowel function intended for the general population (adults and children).”

With this in mind, it is utterly reasonable that scientific studies of subjects suffering minor depression or anxiety, as is the case with many clinical studies evaluating the effects of St John’s wort, are considered as an appropriate basis for substantiating mood enhancement health claims for food supplements containing St John’s wort.

Moreover, because evaluation of health claims for botanicals and related substances have yet to be evaluated and are considered “pending” after being put on hold by the European Commission in September 2010.

This means, under the terms of the transitional measures within Article 28 of the EU Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation (1924/2006), that national rules for claims apply to those claims that were already in legal use prior to the entry into force of the regulation on 1 July 2007. This provision is certainly applicable in the case for non-medicinal, mood enhancement claims for St John’s wort in countries like the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands, among many others.

Foods, food supplements and lifestyle choices are among the many ways that people can manage their own health status and it is absolutely fitting that consumers should be empowered to do this, with access to a diverse range of products, including food supplements.

Fig 2. Separating medicinal actions from normal physiology in terms of the parameters given in the EU medicines definition (Article 1.2, Directive 2001/83/EC, as amended)

The scientific underpinnings for this come from consensus, including from the Cochrane Collaboration’s review of 29 studies in 2009, that St John’s wort is effective for alleviating symptoms of minor depression. Cochrane summarises that there are no significant safety concerns with St John’s wort extracts per se (“side effects [being] usually minor and uncommon”), however it notes that “the effects of other drugs might be significantly compromised.” This is much more likely to be the case with high dose extracts used as medicines, as opposed to lower dose products more commonly sold as food supplements.

Slippery slope

The challenge against St John’s wort represents part of an ongoing campaign by the UK’s MHRA, generally aided by complaints made by certain trade associations, to attack herbal food supplements without adequate legal justification. Challenges against milk thistle, Echinacea, black cohosh, agnus castus and other herbs have also been made by the UK regulator, the former having been most successfully defended thus far.

Where the claims are clearly not medicinal claims, as in the case with some of the St John’s wort products removed from Amazon UK, the MHRA has no jurisdiction given it is limited to products that are medicinal. In the UK, trading standards and the Department of Health have jurisdiction over food supplements and health claims made on foods and food supplements.

Responding to the recent attack, ANH executive director Rob Verkerk said,

“It is essential in our view that manufacturers don’t simply cave to the demands of the regulators that are often worded to instill fear despite them not necessarily having a legal basis. In cases where there is some doubt as to the categorisation of products as supplements or medicines, there is a statutory procedure that can be used to defend a company’s position for selling botanical food supplements. Companies owe use of this procedure to their customers whenever it’s feasible so that consumer freedom of choice is maintained.”

Further information and actions

- More information on the UK statutory procedure is contained in the MHRA’s Guide to What is a Medicinal Product.

- Consumers no longer able to access products or food supplements manufacturers or suppliers facing challenges by regulators may wish to contact ANH Europe’s office ([email protected]; +44 (0)1306 646 600) for further information.

- Herbal food supplement manufacturers, EU-wide, should come together to agree a maximum daily limit for an agreed active ingredient (hypericin and/or hyperforin). Such a limit of 700 mcg/day has already been set in Belgium for food supplements containing St John’s wort and although possibly over-cautious, it could act as a useful starting point. ANH Europe is currently engaged in discussions with several manufacturers and would be interested in hearing from others with concerns about regulatory action against their products. Please contact [email protected]; +44 (0)1306 646 600.

Comments

your voice counts

11 March 2015 at 11:16 pm

The harder these fools push the faster they will force the revolution to happen ...

My patients say they've allowed their bodies to eliminate all traces of cancer with RSO ... I refuse to hide that fact ... And as its stated in a testimonial ... It's not my words and I didn't say 'cure' but I will imply that fact very strongly because it is a fact benificial for people to know.

Another benificial fact to know is that all disease is the same thing - chronic inflammation. Everyone knows this industry is pressed to invent new names for inflammation in different parts of the body to make an industry run by intellects making health confusing for the layman ... When in reality health is simple. that's the truth!

Their attempts to suppress information and people finding out about how much of a big joke the health system is will only backfire faster than if they did nothing ... Good luck system ... But your carving out your own demise

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences