A large number of UK herbalists have long hoped that their push for statutory regulation (SR) of their profession would give them a more secure footing in the healthcare system, give the public more confidence in herbalism and would also improve herbalists’ access to unlicensed manufactured herbal products.

But after a little over four years since the UK Health minister Andrew Lansley announced his promise to grant SR to UK herbalists, the rug appears to have been firmly pulled from under foot.

Lead author of the report, entitled “Report on the Regulation of Herbal Medicines and Practitioners”, was UK Deputy Chief Medical Officer, Professor David Walker. The report was prepared after discussions held by the Herbal Medicines and Practitioners Working Group, co-chaired by Prof Walker and David Tredinnick MP.

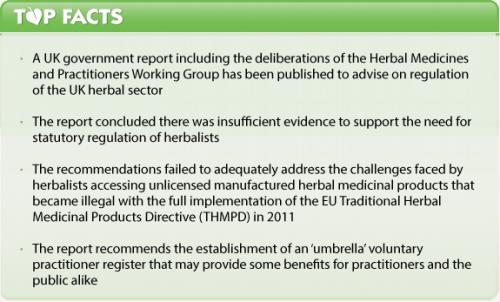

In short, a plethora of obstacles have been used by Prof Walker and his team to provide a blockade against SR for herbalists. Among the main reasons cited were: insufficient evidence of safety and efficacy, complications in EU and UK law, and government policy in the form of the current government’s ‘Enabling Excellence’ command paper. All of this and more has been used to say ‘no’ to SR and a ‘possible maybe’ to voluntary self-regulation, assuming more of the right kind of data are accumulated. That of course might be years away.

About the report

The report is intended to advise the UK government on how to regulate the sector. The Working Group had brought together representatives from the main herbal traditions, the Herbal Medicines Advisory Committee (HMAC), the Department of Health and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), to assist “in examining the options for regulation of herbal products and practitioners in the light of the new European legislation”.

‘No evidence’ to support need for SR

One of the main aims of the Working Group was to examine the feasibility of UK herbal practitioner regulation on a statutory or voluntarily self-regulated basis. Despite the prior government promise back in February 2011 to deliver SR, Professor Walker concluded that “despite strong calls by many for statutory regulation, there is not yet a credible scientific evidence base to demonstrate risk from both products and practitioners which would support this step”. In addition, he said that the “limited evidence of effectiveness of herbal medicines in improving health outcomes” makes it difficult to establish the necessary good practice boundaries. Instead, he recommended that the sector organisations develop an ‘umbrella’ voluntary register, and collaborate on collecting safety data, developing standards, establishing an ‘academic infrastructure’ for research and training. In due course, he added, the voluntary register could seek accreditation from the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA). Meanwhile, he recommended that the government should support further research “in order for an evidence based decision to be made about the level of assurance required to ensure public protection”. Many, but not all, herbalists have long argued that public protection is best served by the immediate statutory regulation of their profession.

Non-Western herbal traditions remain in limbo

The other key aim of the Working Group was to explore ways of ensuring legal access to the widest possible range of herbal products for UK practitioners of all traditions. UK practitioner access to unlicensed, manufactured herbal medicinal products ceased when the herbal exemption for their use (under Section 12(2) of the 1968 Medicines Act) was revoked on 1st May 2011, at the time of full implementation of the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (THMPD) (2004/24/EC).

Although something of a technicality, Professor Walker incorrectly states in his report that the THMPD “effectively banned the importation and sale of large-scale manufactured herbal medicine products…..[which] severely limited the scope of some herbal practitioners to continue practising, particularly those from the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurvedic traditions.” Technically, the THMPD is an optional simplified registration scheme for compliant herbal medicines. It was the UK government’s decision to revoke Section 12(2) of the 1968 Medicines Act that actually caused this loss of freedom.

Also ignored in this report, is the zealous and current efforts by the UK medicines regulator, the MHRA, to challenge products with long histories of use as food supplements when they have been awarded licenses under the THMPD scheme. This is despite, in many cases, long histories of their sale in the UK and elswehere in the EU, as food supplements.

UK government recommends a ‘more proportionate way forward’

Professor Walker does however recognise in his report that the THMPD is actually not suitable for non-Western herbal traditions practicing in Europe, including Ayurveda and TCM, traditions for which it was originally intended. Let’s not forget this fatal problem was recognised even by the European Commission as early as 2008, yet it also has been unable to deliver any kind of a solution as yet.

Professor Walker’s report offers no quick fixes for herbalists’ access to herbs, either. He acknowledges that many herbal products fall outside the scope of the THMPD, and that there are those who have “called” for a challenge of the directive. He suggests that in the longer term “the UK government may wish to invite the European Commission to review the operation of the Herbal Directive” but this my prove somewhat awkward given the central role played by the MHRA in developing the final form of the THMPD.

In the meantime, his key recommendations include that “the government should consider the feasibility of a systematic review of herbal ingredients, drawing on existing legal frameworks with a view to amending current lists of known potent or toxic herbs, where sufficient safety concerns are raised”, that the MHRA, Department of Health and/or other relevant government agencies “should review the food lists currently in development and consider whether these could be used to assist the UK’s assessment of the status of herbal products”, and that the government “should consider further the idea of a system that would allow small scale assembly of products off-site on a named patient basis using a ‘dispensary’ type approach”. It comes as no surprise really that the UK government, doubtless under pressure from EC institutions, the media, skeptics, and in the run-up to a general election, would do anything other than further drag its feet on herbal issues.

Could food supplements be the saviour?

Professor Walker also considered the various debates held by the working group on whether a more permissive UK stance on food supplements may provide herbalists with greater access to products. This is after all is a common approach in many other EU member states, hence the development of the PlantLIBRA project and increasing interest in the draft BELFRIT list.

But, again, the door is closed on this option almost as quickly as it is opened. Prof Walker argues that food supplements is not a category of much relevance to herbalists given most products herbalists are interested in using would “clearly fall under the definition of a medicinal product.” He fails to say that any food ingredient with therapeutic properties would equally be classified as a medicine given the bizarrely broad scope of the definition.

Other options

The off-site dispensary approach alluded to as a possible recommendation for further investigation could present one herbalists with significantly more options to access products and it potentially parallels the compounding pharmacy model used widely in the USA. But the report also makes clear there would need to be a lot of work to find a proper legal foothold for such an approach, that didn’t conflict with EU laws or existing services offered by existing UK pharmacies.

EU medicines law no help to herbalists

The UK government had earlier also dashed herbalist hopes that Article 5.1 of the EU Human Medicinal Products Directive (2001/83/EC) would provide an exemption for their use of unlicensed herbal medicinal products, as ‘authorised health-care professionals’, through SR. This clause was to allow ‘special’ prescribing of unlicensed medicines to named patients, by medical doctors and pharmacists. But a European Court of Justice (ECJ) judgment in a European Commission (EC) against Poland made it clear that Article 5.1 is to be strictly interpreted and applied only in exceptional circumstances.

That leaves UK herbalists where they've been for years, with the rather weakly worded exemption in Regulation 3(6) of the 2012 Human Medicines Regulations that in turn replaced Section 12(1) of the 1968 Medicines Act.

Where to from here?

The report is simply advice, so no action can be taken until a government acts. What's for sure, is that even with all recommendations accepted, there will simply be agreement to do more work to eveluate the 'best' way of further regulating herbalism. Alternatively, it could be seen to be playing a political game: on one hand the herbal sector gets to feel it's being listened to, and on the other hand, mainstream medical interests that have long been down on herbalism needn't worry that herbalism will be granted a seat at the top table of healthcare.

We'll keep you posted as and when there are actions on this issue which might be relevant.

Previous articles on these UK herbal issues:

Stop the UK government doing a U-turn on herbal medicine promise

UK herbalist regulation: Statutory, voluntary or the status quo?

Progress for UK herbal practitioners: Do the best things come to those who wait?

Comments

your voice counts

09 April 2015 at 12:46 pm

I like all the herbal medicines but myself in south africa have been victimized & abused by so many many corrupt health shops & so on & because of the present outbreak of bad natural health shops & docs , almost every herb here has been infected with horrific black-magic & then they spy on you at home , then the taste & swallow of the herbs are raped & abused by these mafia syndicate telepathic spies ;& their new philosophy is that one must be made sick to have remedies or clays .& they do use grips . many people are already 100% super super healthy & use remedies to maintain & enjoy .....& as well any herb now has no effect at all & it is really a terror nightmare ; & still no move has been made to make protections for the products & nice codes of conduct etc. & can foresee this getting worse in the near future. it is like living with trauma shell shock every move you make alone at home is being watched & interfered with harassed. & obviously also the big pharma want now to own the herbs & have all the money . but of the herb people were really ethical , at least this battle could be better won by the right side .

10 April 2015 at 11:24 pm

In South Africa the government opened professional registers for Phytotherpists. The results have been tragic for all involved. Elitism among those few who were registered has resulted in them shunning and attempting to ban and censor non medical herbalists. Promises of integrating Phytotherapy into the NHS turned out to be empty promises.

I believe that although UK Medical Herbalists will be saddened by this report, it's probably a blessing in disguise. Once National Health Departments take CAM professions under their banner (control), they make sure the fundamental health tradition and paradigms are discarded and replaced with biomedical systems, resulting in practitioners becoming body mechanics and symptomatic medicine pushers.

11 April 2015 at 12:31 am

Robert Scott

Where do we go from here?

I’m going to address this subject a little obliquely as I think this is probably the best way to engage the creative thinking process.

Several years ago, I was asked to address a support group of DHS claimants who had found themselves so psychologically and emotionally damaged that they were effectively like shipwrecks washed up on the beach of life. The support group was run by a councillor who promoted rather than resolved their identity of victimhood. I am sure that every experienced therapist will have come across patients who have fallen foul of this sort of experience.

I gave my talk on the scene of “why am I here”. The format of the talk was to investigate the meaning of each of those 4 words.

1. Why – is it because I am a victim who has no choice or control of my life, or is it because I have purpose and direction and this is part of my plan?

2. Am-this aspect investigated the nature of being and the reality of life from the perspective of Descartes.

3. I-this addressed the nature of the individual identity and touched on areas of spiritual awareness.

4. Here-this investigated the concepts of the place where the individual is found themselves within their own lives, the nature and purpose of their Incarnation and of course why were they sat in this room listening to me.

The results of this talk led to the majority of the group waking up and taking control over their own lives. Realising that they were not victims but the masters of their own destiny, they left the group (which subsequently collapsed) and were able to get on with their lives.

When you come to contemplate the subject of the way forward, you 1st have to evaluate 4 basic concepts. The 1st one is to establish exactly where you are now. The 2nd one is to evaluate whether or not it is where you want to be. The 3rd one is to establish exactly where you want to be if you’re not already there. The 4th one is to establish how you intend getting there. You cannot establish a direction of travel before 1st discovering where you actually are and the rest depends on why you are there, hence the relevance of my starting comments.

Herbal medicine, like many other therapies, stands in the category of complementary and alternative medicine. The failed quest for statutory regulation must confront the National Institute with something of a crisis of identity. Up to now, their sense of direction has been effectively based on the identity of complementary medicine, seeking validation from association with and acceptance by an organisation based on allopathic practice. Seeking validation of this nature must demean their sense of self-worth, which in turn, from a psychological point of view, would de-skill them as confident practitioners. The belief that they are in some way be hindered in their practice, without the approval of the HPC is a scandalous lie, of which they seriously need to be disabused.

In my humble opinion, they should no longer pursue the self-limiting image of complementary therapists but take on the mantle of alternative therapists, offering an effective and dynamic alternative to the toxic offerings of the pharmaceutical industry.

The current situation has placed them at the crossroads. These 2 choices offer them the choice of direction and the way forward is the method by which they choose to get there.

There is of course the saying that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”! If herbalists decide that their role is already to offer a dynamic and effective alternative to toxic pharmaceutical drugs, then they are already exactly where they need to be and all they need is the self- validation and belief in what they are doing, with the same passion that originally brought them to study herbal medicine in the 1st place.

We all stand in the here and now, not some mythical future. Being here and now, it is our job to deal with it as best we can under the guidance of our personal truth. By doing this we transform the here and now rather than discard it in pursuit of some ill-conceived green grass on the other side of an imaginary fence.

Several years ago, a then director of the EHTPA told me that the nature of traditional herbal medicine does not academically belong under the heading of “science”. Instead, it should be taught under the heading of “humanities.” This would allow the inclusion of its energetics, spiritual aspects and life force of the herb involved. This is a subject that I have raised with government on many occasions over the past few years. It is for this very reason that the pursuit of HPC regulation, with the limiting qualification of a science degree, automatically involved a major threat to the future teaching and subsequent practice of all genuine traditional medicine, be it Western, Chinese, Ayurvedic, Unani Tibb or indeed any other tradition from around the world.

Bearing all this in mind, I think the message that needs to be brought to the wold of herbal medicine is that they need to rediscover the original nature of herbal medicine, so that they become better equipped to practice it and to wake up and recognise why they are doing it in the 1st place. After all, if they really are so besotted with the world of allopathic medicine, they would have been more true to themselves if they had trained as conventional doctors.

I perfectly understand that some individuals may find my thoughts and opinions unacceptably challenging, while others hopefully will feel that I’m speaking to their hearts.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences