Rob Verkerk PhD Executive and scientific director

On the back of a study published last week in Cell Reports led by Prof Stephen Simpson at Sydney University, various media, such as the Sydney Morning Herald and Medical News Today have used the opportunity to lambast so-called carb-free or low carb diets. This – excuse the pun – feeds directly into a growing, media-supported movement, against low-carb aficionados, epitomised by a recent article in the UK’s Daily Mail.

Is the low-carb attack justified?

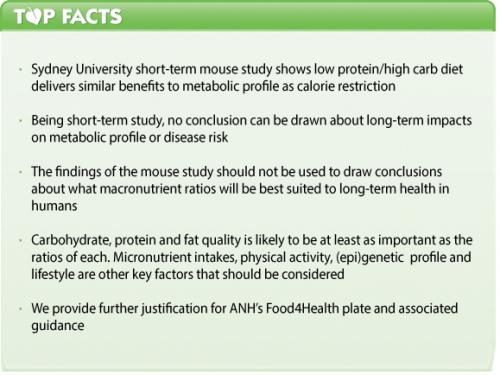

There are a few key points that emerge from the Cell Reports study. These are:

- It’s a short-term (8 week) study on mice, not human

- It aimed to find out how 3 different ratios of protein to carb (5%, 33% and 60% protein respectively, with fat remaining constant at 20%) altered several key metabolic parameters when freely available (ad libitum conditions) as compared with in calorie restricted conditions (40% fewer calories)

- The three different protein to carb ratio diets contained the same level of calories given that only protein and carbs were manipulated, and each delivers the same caloric value (4 kcal/g)

- Among the main results were: calorie restricted mice gained less weight (and unsurprisingly ate less food) than those in ad libitum conditions; the metabolic profile of the high carb/low protein group in ad libitum conditions was better than the high protein group, and on par with the calorie restricted group

- The high carb/low protein group expended more energy, consistent with our understanding that high caloric intake induces thermogenesis

- The experiment didn’t evaluate effects of different qualities of protein, carbs and fat

- The 5% protein level equates to just 25g a day for a human, based on a 2000 kcal/day diet - that's less than half the amount viewed as the human protein requirement as determined by the FAO/WHO

Based on the findings, we consider that media hype using this study to push people away from low carbohydrate diets and back to high carb ones is not justified. Worse, it could serve to push many people back to the low fat/ high simple carb eating habits that have been a major driver of the current type 2 diabetes and obesity epidemic.

What should we take away from this study?

- The study provides some useful information on short-term effects of different protein/carb ratios in ad libitum vs calorie restricted conditions, but it is equally possible that if the quality of protein, carbs and fats were manipulated, or micronutrient levels altered, different results would be achieved

- Conclusions about the long-term effect of the high carb/low protein regime cannot be drawn from this study, the duration of which equates to the equivalent of around 6 years of human life. Extrapolating any of the results to humans should be made cautiously owing to considerable and important differences in metabolic profile, pathogenesis and life history

- The low protein/high carb diet that yielded a metabolic profile (blood glucose, insulin, insulin resistance and blood lipids) on par with a diet with 40% restricted calories had such a low protein level (5%) that has been demonstrated elsewhere to be insufficient for long-term health, or during life stages or times of high protein need, such as reproduction or under immune challenge

- The apparent value of high carb intakes cannot be translated to mean either that high carb intakes, or low protein intakes, are beneficial in themselves. This is because numerous other factors may affect the metabolic profile, especially in the longer-term. These include: the composition and quality of the three macronutrient groups; the availability of specific micronutrients that drive nutrient-sensing systems such as mTOR, AMPK and SIRT, and; the type, duration and intensity of physical activity

- The 5% protein level in the high carb offering, even based on internationally recognised authorities such as FAO/WHO, does not provide enough protein for essential human functions, especially not during life stages or under conditions when the requirement is known to be higher than average e.g. peruods of rapid growth, during pregancy, after intense/endurance exercise, under immune challenge, for the elderly.

Should you change the way you eat?

There is nothing in the Cell Reports study that we believe should alter the guidelines we have given as part of the Food4Health Plate that we publicised earlier this year.

Critical to any interpretation of what high or low carbs means is the quality of the carbohydrates, and of course, quality applies equally to proteins and fats. There is a real danger that the study could be misinterpreted so as to give a green light to go all-out consumption of simple, starchy carbs and sugars. It is widely recognised that this over-consumption of high glycaemic carbs is at the route of today’s type 2 diabetes and obesity epidemic, alongside insufficient physical activity.

Also, reducing or removing gluten-containing grains, or even all grains from the diet, doesn’t mean that carbohydrate intake will be low. The Food4Health plate, which recommends veggies at about 40% by volume, and fruits at 10% volume, contributes to around 40% of all energy from carbs, even though gluten-free grains comprise only 10% of the plate. That’s because vegetables and fruits are themselves largely carbohydrate – as well as being fantastic delivery systems for phytonutrients, some of which are crucial modulators of metabolic, endocrine and immune function.

Some dieticians argue that removal of entire food groups is either difficult or dangerous, and that high carbohydrate diets are ideal, especially if carbohydrates are derived from wholegrains.

Over-processing is a problem for sure, as it removes valuable fibre and micronutrients. But a combination of over-cooking and over-processing can turn a food that is labelled as wholegrain into one that has a glycaemic index higher than white rice or pasta! To understand this better, we strongly recommend you use the GI Calculator developed by Dr Jennie Brand-Miller’s Human Nutrition Unit, School of Molecular Bioscience at University of Sydney to inform your choice of low glycaemic carbs.

The Food4Health plate proposes gluten-free grains and carbohydrate sources only. This is because a large sector of the population, possibly 50% or more, have some degree of sensitivity to wheat or gluten, some of which may not have clinical manifestations for years.

Finally, don’t forget that factors such as meal frequency and physical activity (type, duration and frequency) are at least as important as macronutrient and micronutrient composition in affecting your metabolism, vigour and overall health. Because we are all different — phenotypically, genetically and epigenetically — and we have different lifestyles, there isn’t going to be one plan that will work for all people. But simple and generalised guidelines, such as leaving at least 5 hours between meals, avoiding snacking, and exercising at least an hour a day, can go a long way towards establishing metabolic equilibrium in the majority of people.

Comments

your voice counts

25 June 2015 at 8:57 pm

All you really need to dismiss this study as having any relevance to humans is the fact that the research was on mice.

Anyone with a little knowledge of rodents, and of the fact that findings in non-humans translate to findings in humans with an average predictability of a coin-toss, will not waste time reading or reporting animal studies.

In the case of rodents, surely it is well-known that their natural diet is high in carbs. Therefore that is the diet that is healthy for them.

Your human studies are generally informative and interesting - best to stick to those!

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences