By Timi Ellinas, ANH-Intl strategic alliance coordinator and Rob Verkerk PhD, founder, executive & scientific director

The public, governments and nutritionists the world over must be getting the message: a low-fat diet, the staple recommendation for three decades are out of vogue. They’re part of the problem, not the solution. A meta-analysis involving 68,000 adults just published In The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology journal has added credence to the value of diets higher in healthy fats. It confirms that low-fat diets simply don’t help weight loss and our fight against obesity.

There’s controversy over some high fat diets, such as Atkins-type ones, and the Mediterranean diet, along with its implicit nod to moderation, manages to maintain itself at or near the top of the list of the healthiest diet around, being good both for the heart and the mind – as well as for a long life.

The question is, with all of the nutritional knowledge garnered over the last two millennia, should we just plump for the traditional Mediterranean diet, or does it have its limitations? Are there elements that make it less healthy, or can it be adjusted to improve it further?

The Ancient Greeks had an intimate understanding of the concept of food as medicine. They took the debate to the agora, where philosophers and physicians alike considered the topic in depth. They saw nutrition as so much more than mere sustenance and considered what, when and how to eat with great reverence, recognising that the diet was a precondition for the wellness of both body and mind. Diet was used for disease prevention and specific foods were given as medicine in cases of disease.

In the 5th Century BC, the physician Hippocrates, after whom the ‘Hippocratic oath’ taken by all doctors is named, wrote a treatise on the role of nutrition and diet in the treatment of disease. In his collection of medical works, the Corpus Hippocraticum, Hippocrates emphasises the importance of diet in nosology and therapeutics. Many other famous Greek physicians from the ensuing centuries, such as Erasistratus, also discuss the significance of diet for good health..

Plato’s concepts of a healthy diet are as relevant today as they were then, but it has taken nigh on 2,500 years to have them backed by scientific evidence.

MedDiet to Modern Diets

We understand now that the health of a population has a lot to do with the interaction between our genetics and environment, nutrition being probably the most intimate aspect of our exposure to our environment. Our species’ genetic profile has not altered significantly over the past 10,000 years or more, but major changes have occurred to the quality and quantity of our food supply, and of course to our physical activity profile and energy expenditure.

As we succumb increasingly to so-called lifestyle diseases, there has been growing interest in a return to traditional eating practices and lifestyles, as well as attempting to validate them scientifically.

A useful review by Dr Artemis Simopoulos, a nutritional advisor to the US government, characterised the deleterious changes in our diets as follows:

- Increase in energy intake and decrease in energy expenditure

- Increase in saturated fat, omega-6 (n-6) fatty acids and trans fatty acids and a decrease in omega-3 (n-3) fatty acid intake

- Decrease in complex carbohydrates and fibre intake

- Increase in cereal grains and a decrease in fruit and vegetable intake

- Decrease in protein, antioxidant and calcium intake

Cretan diet – the model variant of the MedDiet

The 1950s diet of the Greek island of Crete has been widely upheld since the work by Professor Ancel Keys and colleagues in the Seven Countries Study as among the healthiest in the world. Rural Cretan residents were found to have the lowest rates of cardiovascular disease, followed next by the Japanese. Cretans were found to live around 50% longer than contrasting Northern European populations.

Among the key beneficial nutrients in the Cretan diet are:

- Antioxidants – especially resveratrol from wine and polyphenols (principally tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol) from locally-produced unrefined, cold-pressed olive oil

- Anti-inflammatory nutrients among which n-3 fatty acids, oleic acid [(n-9) fatty acid], vitamins B6, B12, C and E, some of which have been shown to be associated with lower risk of cancer, including breast cancer, as well as folate and phenolic compounds

- Relatively high levels of the mineral selenium

- A balanced (e.g. 1 to 2:1) ratio of n-6 to n-3 essential fatty acids (EFAs), rich in short-chain, n-3, α-linolenic acid (ALA) found in purslane and long-chain n-3 fish-derived fatty acids, namely eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)

- High fibre intake from vegetables and fruit

The Cretan diet of the 1950s was found to be comprised of an abundance of fruits and vegetables (including wild plants such as dandelion leaves, artichokes, nettles etc.), nuts, low cereal intake (more sourdough bread and less pasta), locally-sourced olive oil as the principle fat, more fermented dairy as cheese and yogurt rather than as milk, more fish and less red meat and finally wine in moderation with meals..

You don’t need a time machine to get yourself back to Crete in the 1950s to experience the benefits of this diet. The pioneering Lyon Diet Heart Study managed a variation of it with considerable success. Dr Michel de Lorgeril’s group found that not only was the modified Cretan diet palatable to the local population but it continued to provide a cardioprotective and cancer preventative effect. Also, this dietary pattern had a lower environmental footprint thanks to its higher consumption of plant-based foods over animal ones, when compared with typical Western diets.

The good stuff

Oleic acid

Olive oil is high in the monounsaturated fatty acid oleic acid [18:1, (n-9)] existing in its triglyceride form, which humans cannot produce and therefore obtain from diet. The high monounsaturated fat intake has been correlated to lower coronary heart disease (CHD) rates. It has been well documented that such a dietary model decreases low-density lipoprotein (LDL-) cholesterol. It has also been demonstrated that oleic acid plays a role in hypotension. In a study conducted by Teres et al, it was determined that high concentrations of oleic acid in olive oil accounted for its hypotensive effect. Increased levels of oleic acid intake were directly correlated to greater oleic acid presence in cell membranes, which through a cascade of events, finally modulate G protein signaling and directly lead to a reduction in blood pressure. Furthermore, oleic acid has also been shown to express anti-inflammatory activities. Reyes et al, found that in the presence of oleic acid, the gene expression of anti-inflammatory macrophages was increased. Macrophages are immune cells that are critical in modulating inflammation and can be polarised to promote or inhibit it, but also have an important role in the removal of excess fatty-acids.

Polyphenols are secondary metabolites of plants and are generally involved in ultraviolet radiation protection, and fight oxidative stress and aggression by pathogens; they are commonly known as antioxidants. In the traditional MedDiet these compounds are readily found in high quality olive oils (unrefined, extra virgin) as well as in wine.

In addition to their protective role in age-related diseases, polyphenols also have robust anti-inflammatory properties. Studies have shown that the oleocanthal, a phenol compound, behaves analogously to ibuprofen, revealing a positive effect in the protection against strokes. Like other molecules in this group there have been significant correlations to the presence of polyphenols in the human diet and reduced risk of CVDs, hypertension, LDL-cholesterol and certain cancer types.

The n-6 to n-3 fatty acid ratio

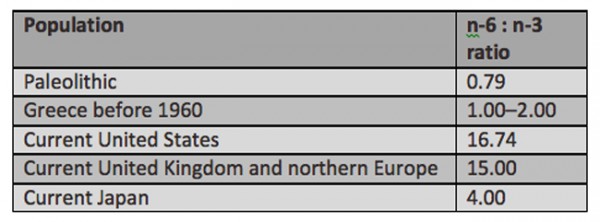

One of the main functions of EFA in the body is as a precursor for eicosanoids, which are mediators of inflammation and cellular growth. Research has expressed the importance of the right balance [(n-6) to (n-3)] amid the EFA classes rather than the absolute level. The traditional MedDiet was a source of this favourable (n-6) to (n-3) ratio and was calculated to be between 2:1 and 1:1, near to that of the Paleolithic diet (Table 1). The ratio of (n-6) to (n-3) fatty acids during evolution was 8 times less than it is today, with a lower value of (n-6) fatty acids (i.e. 2-1:1 versus 16.74:1, respectively). This ratio plays an important role for appropriate growth and development but also in the prevention and management of CHD, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, arthritis and possibly cancer.

Table 1: Ratios of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids in various populations

Source: Simopoulos, A. J. Nutr. 2001; 131 (11): 3065S-3073S.

In humans, both these types of essential fatty acids are metabolised to longer chain fatty acids, increasing the chain length and degree of unsaturation. (n-6) and (n-3) fatty acids compete for the desaturation enzymes, delta-5 and delta-6 desaturases, but the enzymes favour (n-3) to (n-6). Conversely, increased levels of (n-6) fatty acids in the diet, found in western diets, interfere or slow down the metabolism of LNA to EPA and DHA, which have been shown to decrease the expression of inflammatory markers that have been associated to CVDs and other systemic diseases.

The not so good stuff

It’s important to not be religious about traditional diets. Even the classical MedDiet has its limitations. It’s just that the benefits for most people outweigh the risks, so the health outcomes for those adhering to the diet are greater than those who consume a standard western diet. The current status of nutritional research suggests there are four common components of the classic MedDiet that might present health challenges for some, and this may lead to chronic diseases in the longer-term.

Gluten. Wheat isn’t a big player in the Cretan MedDiet, and the overall gluten concentration is low, although it is still enough to stimulate inflammatory responses. When wheat is consumed it’s in sourdough brea where the lactobacilli are able to substantially reduce the gluten. Unlike the Italian diet, pasta is not a big feature of the diet. The central, structural protein complex in wheat is gluten, making up around 80% of protein within the wheat grains. Gluten is further broken down to glutenins and gliadins, which are best examples of food-derived pathogenesis and separately have been identified in a host of illnesses, such as inflammatory disease that include, ulcerative colitis, asthma, baker’s asthma, rhinitis, contact urticarial, chronic fatigue syndrome and has even been linked to depression. Again, as we described a similar case for legumes, wheat also contains lectins that can bind to enzymes and a number of cell types and damage tissue and organs. Daily consumption of wheat and wheat products, as well as other cereal grains is not advised as its contribution to chronic inflammation and autoimmune disease manifestation is well documented.

Lectins. Legumes are important components of the classical MedDiet and a plethora of recipes for lentils, chickpeas and other beans have been created as a result. The beneficial effects of legumes come especially from the proteins, vitamins, minerals and phytoestrogens they contain. But they may also contain particular lectins called phytohaemaglutinin, that are toxic, inflammatory and resistant to digestive enzymes in higher doses. They can only be destroyed by long periods of cooking or fermentation.

Lectins can stimulate an immune system response creating hypersensitivity and can damage the intestinal lining and increase gut permeability, leading to 'leaky gut'.

Phytates, specifically phytic acid, have the strong ability to chelate minerals, including zinc, producing insoluble salts, and interfering with their absorption in the body. Phytates in cereal-containing foods are among the most important reason for zinc deficiency, which leads to compromised immune systems. They bind non-specifically with several proteins, carbohydrates and can interact with enzymes by inhibiting them. It has also been shown that phytates inhibit some important enzymes like, trypsin, pepsin amylase and glucosidase – all involved in digestion.

Dairy. While sheep and goat’s milk (especially when grass-fed) are nutritionally superior to cow’s milk, the debate continues as to whether dairy products are an essential pre-requisite to the diet. The Harvard Healthy Eating Plate is entirely dairy-free, based on a recognition that dairy intolerance is very common. As we’ve discussed in a previous article, there is more and more evidence linking dairy to several types of cancers, digestive problems and chronic inflammation. It is also a potential risk factor for various autoimmune diseases, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, obesity and heart disease. Some types of milk, such as sheep’s or goat’s milk may be less inflammatory than modern-day cow’s milk, and fermented dairy, in the form of cheeses and yoghurts may not only reduce lactose but provide additional support for the gut microbiome.

Not only have contemporary, modern, industrialised, western lifestyles moved us a long way from traditional, healthy dietary patterns, there has also been a significant decrease in the MedDiet compliance in Mediterranean countries in recent decades. There is a clear parallel trend between a higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, CVDs and cancer on a global scale and the changes that have occurred in modern day dietary patterns.

We are at a turning point of in our understanding of health, with increasing recognition that it is the result of an interplay between our genes and our environment, with the diet being a crucial part of this. We can gain a lot by studying our past, while we refine our understanding with the best of our current scientific knowledge. We need new models of healthy diets that fit contemporary cultures. Therein lies our own interest in what we call a “NeoMedDiet”, that takes the best of the old and couples it with the best of the new. It’s about recognising food as information and allowing our genes to recalibrate and reboot.

“For there ought to be no other secondary task to hinder the work of supplying the body with its proper exercise and nourishment”

- Plato (‘Laws', 807D. Platonic Dialogues).

We’ll back Plato on this every step of the way!

- Among the principles held in such esteem for so long, and now validated by modern science, that most of us can readily incorporate into our everyday diets are:

- Eat in moderation

- Try to balance your n-6 and n-3 ratio as close as you can to a healthy 2:1 ratio

- Consume a wide variety of different coloured fruit and veg, especially the latter, preferably locally sourced and pesticide-free, and try to include plenty of as-wild-as-you-can green plants

- Eat a little more oily fish and less meat

- Use unfiltered, cold pressed extra virgin olive oil plentifully as a healthy source of fat in your diet, and minimise its use for frying given it gets damaged by heat. This healing oil is best consumed raw

- Get some nuts into your diet and your salads

- Minimise or eliminate grains

- If you know or think you have any dairy intolerance, drop it!

You shouldn’t be surprised if this is looking rather like the ANH Food4Health plate! But there’s more that can be done to take the best elements out of a classical Mediterranean diet and make it relevant to our fast-paced contemporary lifestyles. We refer to this approach as the NeoMedDiet, and it combines readily available modern foods, while yielding profound health benefits. Watch this space!

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences