By Rob Verkerk PhD, executive & scientific director

You’ve just got back from your run, cycle ride or gym workout. You know you need to recover. Does that involve feet up in front of the TV? Or perhaps a protein shake? Or is there more? What’s active recovery? We know recovery is important, but do we know what’s involved in a recovery process that might take 5 or 10 times longer than the activity — and associated trauma — that created the need for recovery?

In this piece, based on a presentation I gave at Elite Sports Expo at ExCel in London, last Thursday, we give you a snapshot of some of the latest views on recovery.

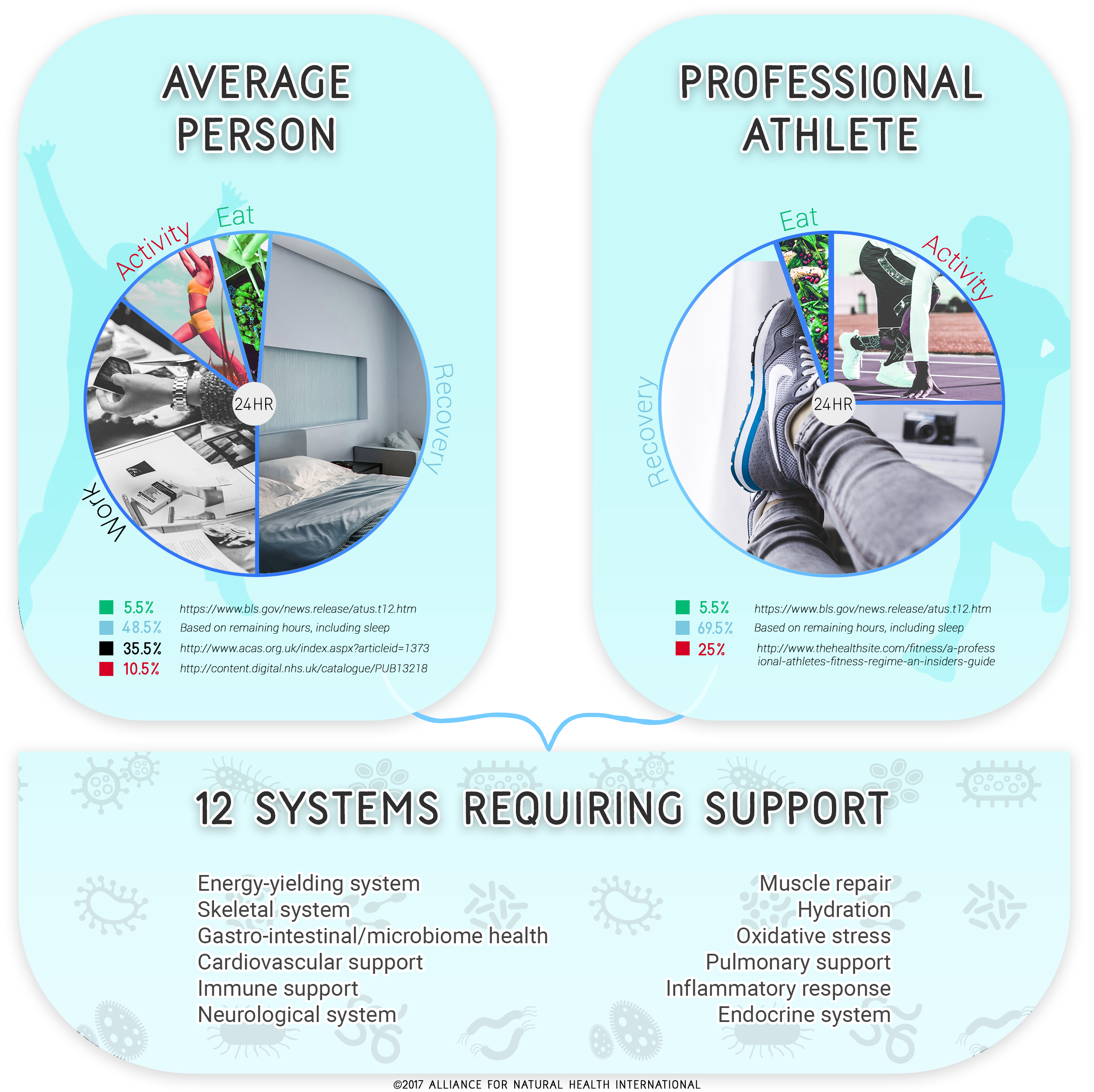

Even professional athletes spend a lot more time recovering than training. Optimal recovery after a training session or an athletic event involves a lot more than just taking a protein shake, sleeping or sitting with your legs up. While all of these can help, to be most effective, we need to make sure we cater for 12 different systems in our bodies. These are shown in the infographic below:

Key elements of the recovery process are:

- Counteracting muscle fibre damage. Damage to muscle fibres and tissue triggers a super-compensation mechanism controlled by hormones and signalling chemicals (kinases) in the body that in turn stimulates increased protein synthesis and growth of muscles, allowing the body to better adapt to the exertion. For athletes or anyone trying to build athletic potential, muscles need a daily protein intake of around the 1.2-1.6g/kg body weight range (i.e. 84-112g for a 70kg adult). This protein should include at least 5g of three amino acids, the branched-chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine and valine in a ratio of 2:1:1. It should not be heavily heat damaged (e.g. chargrilled meats), it should comprise modest amounts of red meat at most, and it can include lectin-free or low-lectin vegetarian proteins such as pea, including supplemental forms. There’s been a lot of research done on timing of protein and carbohydrate intake post-training. Depending on the individual and the intensity and duration of activity, the protein can be taken in isolation, ideally within a 30 minute window of finishing the training or activity, either without or with carbohydrates, in the case of the latter using a 4:1 ratio of complex carbs (e.g. sweet potato, brown rice) to protein, to allow glycogen (stored glucose reserves in muscle and liver) to be repleted.

- Counteracting oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is the result of increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) – also referred to as free radicals – that is not sufficiently counteracted or quenched by the body’s antioxidant system. The effects of free radicals are both positive and negative; they create stimuli which upregulate the immune system, as well as negative effects, such as damage to cell membranes, DNA and the oxidation of proteins and lipids. That means active people need to do what they can to optimise their antioxidant system, which has two main parts; the endogenous (internal) system that includes enzymes such as glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase, and the dietary/nutritional antioxidants that include vitamins A, C and E and selenium along with a wide array of ingredients in fruits and vegetables, herbs and spices. Among the most potent botanical antioxidants are polyphenol- and proanthocyanidin-rich fruits and grape seeds (easier to find these days as an extract in supplemental form), quercetin in citrus peel, and green tea. These need to be taken cautiously just after exercise as too high an intake of dietary antioxidants can blunt the response of our endogenous systems. Some hours after exercise, consuming generous amounts of dietary antioxidants is of course very beneficial.

- Supporting a healthy inflammatory response. Inflammation underpins all chronic diseases and is well understood as being harmful if it’s sustained and persistent, being the ‘common soil’ of multi-factorial, chronic diseases like cancer, heart disease, diabetes, obesity and depression. However, a well-managed, short-term (acute) inflammatory response increases blood flow to areas that need repair, helps fight infection and speeds the healing of damaged tissues. A healthy inflammatory response is aided by a diverse range of nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, but also benefits from adaptogenic herbs like ashwagandha, ginseng (Panax or Siberian) and Rhodiola, as well as anti-inflammatory herbs, including Boswellia serrata and curcuminoids and related compounds in turmeric. Curcuminoids in supplemental form are poorly absorbed in the gut in supplements, unless combined with bioavailability enhancers such volatile oils of turmeric rhizome, black pepper extracts, liposomes, phospholipids and/or cyclodextrin.

- Over-training can lead to immune suppression. Over-training syndrome (OTS) is very closely related to the inflammatory response, as inflammation is the first response to exercise-induced trauma that aims to re-establish normal function and repair. This process leads to an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (chemical messengers that control the immune system) and if an athlete doesn’t get enough time to recover between bouts of exercise, the pro-inflammatory immune cytokines over-power the anti-inflammatory ones, leading to a suppression of the immune system. The ABEL-Sport Overtraining Test by Knight Scientific, in Plymouth, UK is a very useful test being used by leading professional athetes, keen amateurs and Olympians to ensure they're not over-training on the lead up to major events. Apart from adequate periods of rest, that vary according to the severity and duration of the exertion and associated trauma to the body, it is necessary to ensure there are sufficient nutrients in the system that are supportive of the immune system, including zinc, vitamin C and dietary nucleotides.

In supporting all 12 body systems, it is essential that a diverse, plant-based diet, rich in phytonutrients is consumed. Find out more by reading articles in our Food4Health campaign and why you should ‘eat a rainbow’ every day!

Take-homes

- Exercise of moderate to high intensity induces trauma on the body from which you must recover before you proceed to the next round of activity if you want to improve your athletic potential, strength, endurance and resilience.

- Recovery can be passive or active, or better still, a combination of both. Movement of the body is still possible and is beneficial (e.g. lymph) and can include gentle walking, swimming, cycling, rebounding, etc.

- Determine the amount of recovery time needed post training or event according to the extent of the exercise-induced trauma and your current level of fitness. Many wearable devices (e.g. Suunto, Garmin, Polar) calculate this for you after each round of training based on standard algorithms and given levels of fitness and heart rate.

- Consume a plant-based, moderately high protein diet, such as that based on the Food4Health guidelines.

- Avoid protein supplements that induce inflammatory reactions or bloating, e.g. dairy-based (whey concentrate, casein) proteins.

- Consider remedial, sports massage to support repair of muscle fibres.

- Supplement with additional protein, amino acids and supplementary nutrients and botanicals to support the 12 body systems that are most in need following moderate to high intensity physical or endurance activity.

- Be aware of the risk of immune suppression and lack of athletic development from overtraining syndrome, which will require longer periods of rest post-training, less intense or shorter duration training and, more than likely, additional nutrients to improve recovery and resilience.

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences