Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD

Founder, executive & scientific director, ANH-Intl

Scientific director, ANH-USA

It’s a big ask to get people to regain trust in corporates that have perverted the course of our lives – generally for the gain of the few that control them. The banks have done it – yet few have deserted them and resorted to keeping their money under their mattress. Big Tobacco hid the risks of cigarette smoking for over 3 decades – yet 1 to 3 or more in every 10 adults, depending on country, still smoke daily. Big Ag actors, epitomised by Monsanto, have driven a coach and horses through fundamental rights and freedoms, ruling the roost with their own, sick and abusive version of corporate law. But who can afford to go 100% organic? Big Food distorted public health policy on dietary fats by misrepresenting the science, found the bliss-point in ultra-processed foods and made us sick, tired and fat. Yet most still fill their supermarket trolleys on a weekly basis with the processed junk produced by just 10 companies. Big Pharma drugs us into oblivion, literally, marketing its prescription wares aggressively to physicians in full knowledge that the majority don’t work well against our most common complaints while holding their rank as the third biggest killers in most Western societies after heart disease and cancer.

The good, the bad – and us

Twenty years ago, the battle lines were clear. The big corporates – the bad guys – stood on one side of the line. And the good guys, the much smaller ethical businesses that sold wares that made us healthier or made the world a better place, stood firmly on the other side. We then made our choices usually based around how much we cared or how much we knew.

The lines between ethical and unethical corporations are now more blurred. It’s getting ever harder for ‘Citizen Sam’ to determine if a company’s playing the odd card in the ethical game in an attempt to conceal its less ethical activities and improve its image and profitability, or if it’s something more genuine. Big corporates have long had tremendous political power – and even in so-called democratic societies – they have shown great capacity to manipulate the regulatory regime for their benefit at the expense of others. Influencing public opinion via the media and using heavyweight lobbyists are just two common techniques. Full-on coercion may also be involved. Take kids being forced into chemo or radiation against the will of their parents. Or Australia’s ‘No Jab No Pay’ law.

CSR – real or surreal?

As more and more companies become guided by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies, the division between the good and the bad guys is becoming more blurred. Some very large corporations that were not previously well known for giving back to their employees, communities or environment, have got into CSR in a big way – seemingly because it’s good for business. Coca-Cola, General Mills, Proctor & Gamble and Starbuck’s are just a few getting airtime for claimed positive impact on the CSR front.

The unfinished Unilever case study

Then there’s Unilever. Its documentary commitment to its sustainability vision is clear. In my own experience, since Unilever’s acquisition of Pukka Herbs it’s been a hot topic of discussion wherever I go. Many brand devotees are understandably concerned about the buy-out and so they should be. It’s clear that anyone, like me, who had experienced that warm glow from consuming Pukka teas or supplements might be concerned that the acquisition might compromise Pukka’s incredibly strong ethical, environmental and sustainability credentials.

No changes planned at this stage for the ANH-Intl office tea station

All information we’ve received to-date would suggest there is no prospect of any dilution of values at least while the founders, Sebastian Pole and Tim Westwell, remain involved. In fact, there may well be some significant, additional ‘greening’ relating to organic and FairWild certification that goes the other way, back to Unilever. Let’s not be under any illusions. You need only to look at Unilever’s list of brands that include detergents like Surf, Persil and Omo, soaps and shampoos like Dove, Sunsilk and TRESemmé, deodorants like Sure and Rexona, and numerous other ‘non-eco’ brands, to appreciate that ‘greening’ is much needed.

Regulatory burdens

Apart from ethics and sustainability, we also need to look at what benefits companies like Pukka provide to their consumers. The reality is that these companies’ business model isn’t based solely around the premise of sustainability. It’s also based on therapeutics, the bigger mission being to make a genuine difference to people’s health trajectories.

That means operating a business on the infamous regulatory food/medicine borderline, one that is both interpreted and enforced differently in different parts of the world, including in different EU member states.

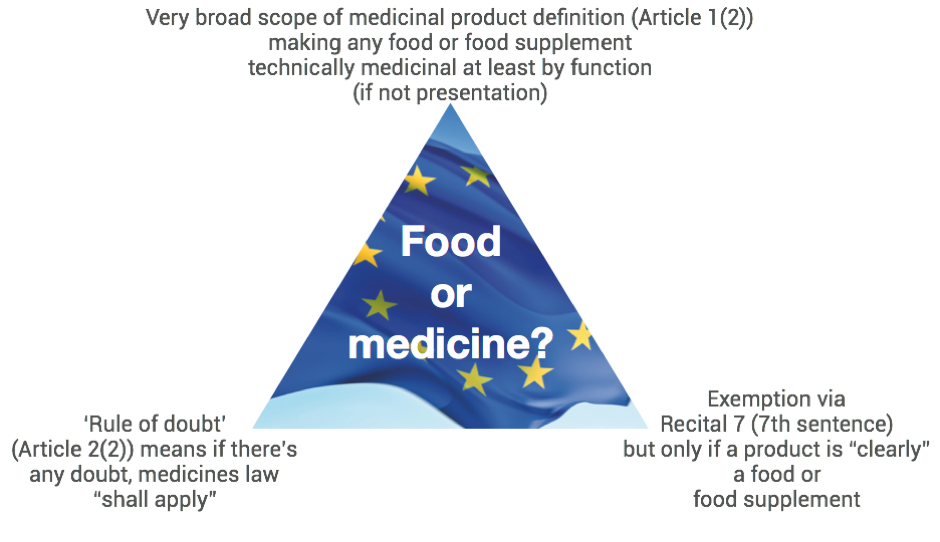

The legal mechanisms in EU law (Directive 2001/83/EC, as amended) that determine case-by-case status of foods or supplements, either as foods/supplements (as per labelling) or as unlicensed, illegal medicines that must be removed from the EU market.

As the body of scientific evidence demonstrating the potent therapeutic function of botanical substances increases, more and more products presently sold as foods or food supplements are likely to be categorised by regulators as drugs, aided by the incredibly broad scope of EU and other drug laws. Looking to the future, it’s increasingly likely, as a group of Italian researchers publishing in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology have just suggested, that a third regulatory category, “beyond the diet but before the drugs to prevent and treat pathological conditions” will be created.

Frankly, small-to-medium-sized businesses simply don’t have the resources to jump through hurdles of this type – this being why ANH has so passionately defended the non-medicinal food/supplement category for the last 16 years. If Unilever’s interest in therapeutic foods and supplements is genuine, might it assist Pukka in negotiating the regulatory hurdles that have already been a significant hindrance to its mission? More particularly, could it become a champion for the sector as a whole? Or would it, like so many big corporates, simply choose to feather its nest while gaining a competitive advantage over those who can’t negotiate their way around the increasing regulatory burdens? Well, it’s probably too early to tell, but I know which of these options I’ll be supporting.

For those not in the know, our consultancy arm, ANH Consultancy has acted in an advisory capacity to Pukka for most its corporate life, one which began in 2001, one year before I founded ANH. Pukka has also been a significant supporter of our campaign and educational work at ANH-Intl. So we know there’s a lot of passion within Pukka to do not only the right thing for the company, its growers, the supply chain – and the environment. But there’s also a deep commitment at all levels of the company to do the right thing by the sector as a whole, knowing that natural health, both practitioner-guided and as self-care, is ultimately the most relevant and sustainable form of medicine for today.

Obviously, the smaller players in the industry will always remain the life-blood of the sector. That’s where innovation, more often than not, is spawned. And rather than being seen as renegades that need to be shut down, driven by a groundswell of grassroots support for wholesome ethics, environmental friendliness and natural therapeutic effects, the smaller innovators are now beginning to influence the offerings of the big corporates.

That’s why Rich Reed, Jon Wright and Adam Balon, the founders of Innocent drinks who sold out to Coca-Cola, set up Jamjar Investments. Like it or not, they saw an opportunity to help other small, promising businesses to build innovative businesses that have a positive impact on people’s lives, much in the way they did with Innocent. Some will question whether the original ideals have been maintained.

But whichever way you look at economic and political power in today’s world, such is the might of the major corporations, I no longer think it’s possible for the small guys to make enough of a difference on their own. THEY are too big, and WE are too small. Goliath needs to change its ways if the world as we know it is to make it through to the end of this century.

Corporate integrity – as well as responsibility

Over the last 20 years I’ve had my sights trained on the notion of ‘corporate integrity’, an idea also picked up by Swiss business ethics researcher Dr Thomas Maak in an article published in the Journal of Business Ethics back in 2008. Maak refers to CSR as a “tortured concept”, one that’s been derailed and which carries a lot of historical baggage – and not good baggage. He proposes transitioning to the concept of ‘corporate integrity’ that incorporates what he calls the 7 C’s of commitment, conduct, content, context, consistency, coherence and continuity. His approach makes a lot of sense to me and it’s designed to sift out those corporates which pay lip service to CSR simply for their own profitability (i.e. most), as opposed to those which have a genuine commitment to positive social and environmental change.

There’s no doubt that big corporates are good at buying out smaller companies with strong ethical credentials. The late Dame Anita Roddick famously sold Body Shop to L’Oreal, and the company’s journey has been far from smooth since, and is now in the hands of Brazilian cosmetic giant Natura. Then there was Innocent and Coca-Cola, with some suggestions Innocent’s influence on the fizzy beverage and food giant has been positive. Let’s not forget Craig Sams’ story with Green & Black’s, Cadbury’s and Kraft. Most recently, we of course have Nestlé’s acquisition of Atrium Innovations, owners of the US’s number 1 practitioner-only and consumer dietary supplement brands, Pure Encapsulations and Garden of Life respectively.

If we use Dr Maak’s 7 C’s lens, I think we’re all in a better position to watch what happens and consider the implications of these acquisitions, including whether Pukka or Unilever are worthy of support, criticism or boycott. Where we can, we should seek to influence the relationship positively. In Unilever’s case, there certainly are multiple signs that the parent company is paying a lot more than lip service to both health and sustainability – but how much of this is down the current leadership of the company? Particularly noteworthy from a health perspective is its sale of its margarine interests including Flora and Bertolli.

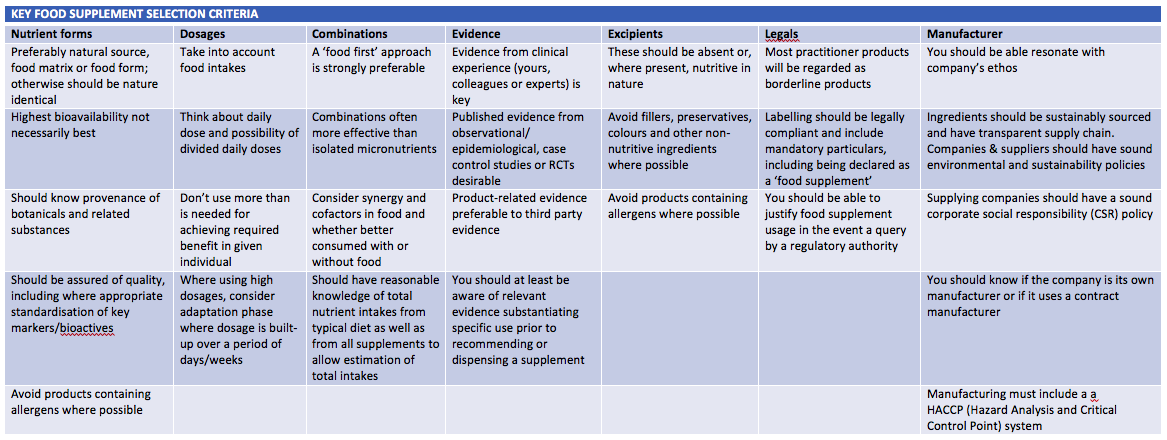

Consumers’ discretion is getting ever more sophisticated. This bottom-up pressure is exactly what’s needed to drive improved standards of ethics and sustainability. By example, following are some of the factors we think consumers should be considering before buying food supplements based on natural products.

Off the rails…

I see it as a good sign that fellow Dutch national, Unilever CEO Paul Polman, is upsetting pillars of big business like Forbes. Forbes’ guest post author Tom Borelli wrote last March:

“At the core of Polman’s problem is his eagerness to put superficial feel good policies ahead of sound business decisions and he is not shy about touting his twisted priorities.

In Polman’s world, “as CEO of Unilever, my personal mission is to galvanize our company to be an effective force for good.”

While Polman seeks approval from global elites and basks in the glory of being called a “sustainability evangelist’” and a world saver for his roles in combating climate change and efforts to address social issues, Unilever has gone off the rails.”

Isn’t that the point? Has Unilever found a railway siding that leads to a place of corporate integrity? Could Pukka assist in any part of this journey?

CEO of Unilever, Paul Polman

It is definitely too early to tell categorically, but being one who is more glass half full than empty, I’m not prepared to be disparaging of the relationship – at least until I see markers that suggest that Pukka’s principles, ethos and passion for sustainability have been disbanded or diluted.

For those of us wanting to see a sea change in corporate social and environmental responsibility that truly is about integrity and making a difference to our lives, our health and the world around us, we need to be prepared to accept there isn’t much time left. The environmental and health challenges we face in the next couple of decades are so grave that unless big corporates change their trajectory now – we, and life as we know it, are doomed.

Time’s seriously running out

If you’re a microbe, an insect, a coral or a tree in a rainforest, that’s probably the best news you could hope to receive. But if you care about humanity and want to support its ingenuity in the face of adversity and its ability to yield a planet capable of supporting many more generations of humans in a world that has many of the qualities and freedoms that so many of us have enjoyed for much of our lives, big things need to change – and fast. And the things that need changing most are linked to how the corporatocracy goes about its business. A destructive, unsustainable ‘business as usual’ approach is no longer an option.

The derailing of big corporates from their destructive trajectories, whether from the inside or the outside, whether voluntarily, unwittingly or deliberately, should now be firmly on all of our corporate sustainability and integrity menus.

As Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr once said: “Many people die with their music still in them. Too often it is because they are always getting ready to live. Before they know it time runs out.”

Let’s not pass on with our music inside of us. Let’s sing out loud, together, from a place of understanding of the complexity and urgency of the issues we face as a global society. And before I get off my soapbox, let me add; while we won’t always agree with each other, let’s do our best to be respectful and maintain our integrity and do what we can to help others, including the corporates, do the same.

Comments

your voice counts

21 February 2018 at 6:53 pm

This is a great blog. It gives real food for thought. I agree 'Big' is often bad but has potential to be a force for good. Lots of prodding from your good self and others in the 'Little' camp should edge them closer to our desired sustainability goals. Keep up the good work! Thank you 😊

23 February 2018 at 2:12 pm

Nice comment, thank you Rachel. R ;-)

21 February 2018 at 7:04 pm

Your report poses the question: "But who can afford to go 100% organic?" Well, the word 'Organic' when used in the context of food standards is a European Trademark, owned by .... Brussels (EU) naturally! Therefore we all need to be PC and display the word Organic complete with the registered 'R' symbol, and to be totally PC, followed by; 'All registered Trademarks acknowledged'.

However, describing anything as 'Organic' is like saying we should all aim for 5-a-day or eat a healthy balanced diet. If a substance contains carbon molecules then it is 'organic' folks! These silly health related slogans have no scientific or legal standard, they are all meaningless and used by the media and professional commentators to 'connect' with the lowest common denominator - i.e. the dumb general public. Certified Organic has been discredited for some time now. The London Health Centre ONLY rely on sight of an independent batch analysis (listing heavy metals, pesticides, toxins etc.) from a leading food safety lab for our raw ingredients and supplements. The proof is always in the printout as we say - never blindly trust a commercially driven Certified Organic organisation if you want to verify exactly what you are about to eat. Concerned about your health? Time to get real!

23 February 2018 at 2:11 pm

I totally agree with your sentiments over the dumbing down of organic standards - but actually Pukka (Sebastian specifically) has been a champion of pushing to stop this. How about organic tea in 'silken' tea bags made from GMO plastic (polylactic acid)? Sebastian was the first to call organic certification bodies on this. I personally am in support of a sustainability standard - that's as much about what you do to the agricultural environment - not just what you leave out of it. Organics is presently just a kind of 'free from' agriculture that doesn't mean soils are being adequately managed, restored or sustained. Best, Rob

21 February 2018 at 7:29 pm

Rob, I am not sure why you suggested this blog might be controversial.

You call it out exactly - it's 5 minutes to midnight - if we don't wake up and take action immediately it will be over. At the very least we need to consume responsibly - both less (much less) and products which don't 'cost the earth'.

Perhaps the only potentially controversial question is whether major corps are capable of holding to the ethics/integrity of the small companies they take over. Time will tell. In the meantime we know for sure that all corps are focused on shareholder pressure for the bottom line. We can disrupt that by changing our buying habits and support movements that take the oxygen out of their profits unless they behave sustainably.

Ultimately the consumer has the power. Our major challenge is making this change before everything we need to survive is produced by a handful of companies who can dictate what is available.

I still believe we can do it but we all need to pull together.

23 February 2018 at 2:05 pm

Absolutely, Carol. I only thought it might be controversial to the degree that some might expect us to support an out and out boycott. Pulling together, as you suggest, has got to be a better option given the specific facts of this acquisition - while moving forward with eyes and ears wide open. Best, Rob

21 February 2018 at 8:06 pm

Thanks Rob. good one.

23 February 2018 at 2:02 pm

Thanks David - looks like 'watchful waiting' might become the norm for us as we continue our journeys towards increased wisdom and enlightenment! Best, Rob

21 February 2018 at 9:04 pm

Nothing is in a vacuum. Nothing in that sense will be 'pure'.

Corporate infrastructures of finance, law, communications and transport effectively manage systems of humans and such systems all operate the optimisation of corporate profit at expense of any other factor that does not impinge on the balance sheet.

Corporate influence owns or effectively controls the regulatory bodies and any other key institutional influence. But corporations are not people so much as legal entities of collective private interests - ie shareholders and appointed executives. But also of cartel interests some of which are relatively in the open, such as the drafting and passing of regulations that operate a canopy of denial to micro and small-scale business - while masking within 'health and safety'. (This of course includes so called 'Trade deals').

Technocracy is an idea and practice of systemic control that requires Big Data as the feedback by which to operate such variables and apparent intangibles as 'people'. Leaks such as in 'Silent weapons for quiet wars' indicate the use of scientific principles for human system control. In this sense science has always had a strand of 'define. predict and control' that masks in beliefs of 'progress' but according to WHO, and by what process of communication or agreement? As you know under certain parameters all rights can be taken away, and of course that means transparency and accountability become at best a circus of narrative control.

Much of law is the law of contract agreements, that are enforceable by law, and I sense there may be ways to use this aspect of the law to make persons behind institutional and corporate fronts accountable - but that is not my area of focus.

I feel to focus in real relationship. In presence and not in narrative identity reactions, and so while I have choice I use it to align in freedom, and in particular to regain the freedom to focus within that which I resonate with as meaningful, worthy and unconflicted in itself. This serves then as the basis from which to see with a different perspective than hopes and fears.

Natural healing is also yielding into and being aligned in our true nature. Every witness to our true nature is a worthy communication, and drawing the curtains on deceits that pass off as true is part of reintegrating, healing and wholeness, now.

Where we choose or accept to be coming from is the determiner of our experience. This requires a much greater honesty than many are yet willing to embrace. They need demonstrable witness to awaken in a like kind. The 'world' offers many examples of hidden or masked agenda, manipulative deceits and willingness to turn a blind eye or not see. This is not unique to the few who manipulate and in some sense predate upon the many. The many accept a degree of unconsciousness in tick boxes and targets running as conditioned identity habits. If we open to a deeper learning, the lessons are not far away!

Responsibility is not guilt - but it may call for owning and facing what we have done instead of outsourcing pain and consequence 'out of mind'.

Awakening responsibility is an individual willingness that extends relationship, rather than a system of incentives that require the sacrifice of individual will to group or collective 'identities'.

If we agree to such an unholy contract, we will have chosen to give away choice to external powers. That has always been the nature of such a pact in a tempt to gain personal power, because of course unless we live from it, we believe we do not have it - and teach ourselves to believe it.

23 February 2018 at 4:58 pm

Some wonderful sentiments and insights here, Brian. As always grateful for your contributions. Best, Rob

21 February 2018 at 11:12 pm

Yes, of course it is better if we hope for the best and create in our minds that Pukka and the other smaller companies will make a dent in their behemoth owners CSR records. But it might as well go the other way. What’s missing is a billionaire entrepreneur with a strong commitment to organics and natural health that can get into a bidding war with the faceless Fortune500 corporates. It would even make business sense to create a real organic ethical corporate empire.

And why can’t the owners resist when they get juicy offers? Did they really spend all their time and energy building an ethical company, so they can cash in and retire for golf on the Bahamas?

And if mega-corporates want to be taken seriously on CSR they should state loud and clear: We are not spending our money on bribing politicians (so called campaign financing and lobbying). They don’t as far as I know.

23 February 2018 at 2:01 pm

Take your point Max - philanthropists and do-gooders with ultra-deep pockets around who are committed to fanning the flames that would initiate the revolution we so badly need are so few and far between. I know most companies struggle to find VCs who understand the issues. Also totally agree that companies need to get a lot clearer about CSR and not just use it to score brownie points while the rest of their business carries on destroying the planet, people's lives, etc. Best, Rob

22 February 2018 at 10:39 am

Apart from the frustrating click-coercion of the sign up box - that is blind to that one is already signed up, there is the design of the site that tends to mean I navigate via the email links. Room for improvement there too.

My comment to the current situation didn't get published as far as my browser shows.

Perhaps seeking to address the issues beneath the symptoms is always met with incomprehension or denial. Why? Because once a struggle has been defined, it operates identity that tends to run on the energy of what it was originally set against.

22 February 2018 at 11:33 am

Hi Brian, thanks as always for taking the time to comment. Your previous comment has been approved and posted to the site. As a general rule the popup will only appear once a month unless you're clearing your cache regularly, in which case it will appear each time you visit the site.

Warm Regards

Melissa

23 February 2018 at 8:13 am

Your best written piece to date. Superb. Says it all. Thank you. I shall be keeping this on my desk as I work towards my Masters degree in Public Health.

Best regards,

Janice

23 February 2018 at 1:38 pm

Thanks Janice - best of luck with your Masters! Best wishes, Rob

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences