Content Sections

How many times in your life have you known something wasn’t good for you and just gone ahead and done it anyway? Whether it was the food you’ve eaten, your choice of drinks, activity (or otherwise) or a relationship. We’ve all experienced what it’s like to proceed with potentially self-destructive behaviours in spite of being fully aware of the warning bells going off in our heads. It’s as if there’s an internal driver demanding that an action be taken despite the consequences.

We all know what that feels like. But it seems that some people are better at veering from the precipice, learning from previous actions and making better choices. Others, it seems, are hardwired to self-sabotaging behaviours and appear powerless to choose a new road regardless of the information in front of them.

This is the very situation we find ourselves in with regard to current global obesity, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and preventable cancers – the four biggest killers in the Western and industrialised world.

Knowing what’s good for us, even having a desire to do what’s good for us, appears to be powerless if internal emotional (and psychological) drivers are demanding salve for different, hidden and distant wounds.

Owning our needs

Our immediate physical needs are easy to recognise and acknowledge. We need air to breath, food to eat, water to drink and sleep to rejuvenate if we are to survive. Without these few basic needs the human race would not still be here.

But what of our emotional and psychological needs? They may be less easy to acknowledge, but they are just as powerful drivers of our health and wellbeing and they must also be satisfied if we are to flourish and be healthy as a species. Our emotional and psychological needs are inexorably linked to our biology too, meaning that if they are not satisfied, they are very likely to contribute to disease down the line. That means health care needs to be focusing a lot more on aspects such as purpose and meaning in life, social connection, connection with nature and clarity of mind that have so far not been prioritised in mainstream medicine.

Human Givens

The Human Givens approach is one of several guided approaches that focuses on re-establishing psycho-social balance within an individual. It originated out of the research by its founders, psychotherapists, Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrell over 20 years ago. The approach provides a holistic, scientific framework for understanding the way that individuals and society work.

The Human Givens framework encompasses the latest scientific understandings from neurobiology and psychology, as well as ancient wisdom and original new insights.

According to the Human Givens Institute, our 9 emotional needs are as follows:

- Security — safe territory and an environment which allows us to develop fully

- Attention (to give and receive it) — a form of nutrition

- Sense of autonomy and control — having volition to make responsible choices

- Emotional intimacy — to know that at least one other person accepts us totally for who we are, “warts 'n' all”

- Feeling part of a wider community

- Privacy — opportunity to reflect and consolidate experience

- Sense of status within social groupings

- Sense of competence and achievement

- Meaning and purpose — which come from being stretched in what we do and think.

How many of your needs are being met at this point in time? If you’re a parent, how many are you helping to facilitate in your children?

Research published in 2014 looked at the association of childhood trauma with inflammation (the common ‘thread’ that links all chronic diseases) in adulthood. The work concluded that men and women may experience trauma differently but share many vulnerabilities which can lead to elevated health risks. And specifically, that emotional eating may be an important target for intervention in people who have suffered childhood trauma.

Our emotional – physical landscape

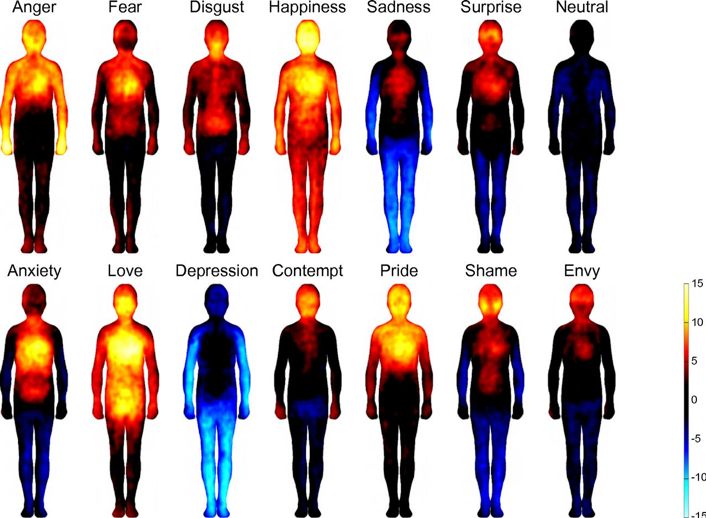

Emotions are not merely thoughts confined to the mind. We experience them in our bodies, which is why they’re ‘psychobiological’, i.e. they drive our biology. Emotions are direct, often visceral, feelings in the body. The stronger the emotion, the stronger the feeling. The heart-racing blush of new love; the ‘butterflies’ in the stomach with anxiety; the palm-tingling, sweating, dry-mouth facing an audience for the first time; the rush of nausea when feeling disgusted, are all familiar sensations for us. And of course, the intensity of the fight or flight response to fear or fright. We are so emotionally fine-tuned that we also use somatic language to describe events in our lives – feeling heartbroken, quivering with excitement, having a gut feeling about something or being sick to the pit of one’s stomach.

Bodily topography of basic (Upper) and nonbasic (Lower) emotions associated with words. The body maps show regions whose activation increased (warm colors) or decreased (cool colors) when feeling each emotion. (P < 0.05 FDR corrected; t > 1.94). The colorbar indicates the t-statistic range.

Source: Fig 1 from Bodily maps of emotions (Nummenmaa et al, 2014)

Wired by trauma – the survivor’s edge

Early childhood/life trauma creates a chronic sense of internal stress and fear that accompanies one throughout life. Because of the way the brain develops, trauma (even during gestation), hardwires a person for ‘survival stress’. This in turn can lead to ways of seeking ‘comfort’ in different guises, particularly food, as an antidote for the unnamed fear inside.

Trauma is transgenerational too, which is why epigenetics – the impact of environment and lifestyle on your genes – is so important in understanding which are the most appropriate interventions in health care delivery.

Indeed, stress, at any time of life, can cause imbalances in neural wiring which, at the cognitive level, affects comprehension, decision making, anxiety and mood. This imbalance drives changes in the body’s physiology via neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune and metabolic changes. If the stress is short term, these changes are temporary. But, if the stress response fails to resolve and the behavioural and metabolic changes persist, appropriate intervention is needed to prevent the creation of disease. Instead of addressing the emotional element downstream, the upstream symptoms are more usually treated and often with drugs alone. These generally only treat the symptoms and often have side effects, sometimes serious.

It’s all in your head

Rarely does the mainstream medical community make the connection between our emotional health and our physical health when it comes to addressing metabolic imbalance or chronic disease. Instead, too often, when a clear cause and effect relationship can’t be established, patients visiting their GPs are told that their symptoms are psychosomatic and made to feel like they’re time wasting. The Guardian published an edited extract from “It’s All In Your Head”, by neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan, which perfectly illustrates how powerful our mind/body connection is.

It’s not just mainstream healthcare that’s guilty of separating our bodies from our emotions. When it comes to diet and lifestyle, public policy and health advice presupposes that everyone is unencumbered by emotion and able to act on the education they receive. When they don’t, a great deal of time, effort and money is spent on finding new, usually more hi-tech, ways to trigger that all important hot button. But what if we’re actually seeing an epidemic of emotional pain and not an epidemic of chronic disease? We know the current reductionist healthcare model isn’t working in the area of chronic diseases, but how will any health system ever be effective if it doesn’t start to prioritise approaches that address emotional health before it manifests into a plethora of downstream diseases?

Creating a positive space for behaviour change

Food being so integral to our survival, as well as to our earliest memories of comfort, love and security, is particularly wired to emotion. Many of us turn to food as an antidote to stress and challenging emotions, or to cope with something unpleasant in our lives. Conversely, many children are still rewarded with sweet treats setting up habits of a lifetime as they’re also associated with happy memories.

As a species built for famine and not for feast, our DNA is hardwired to indulge when we are faced with abundance in order that we had stored fat for the lean times. It’s how we survived through evolution. The challenge for us now is that we’re surrounded by abundance, yet our genes keep telling us to indulge. But emotional and ‘survival’ hunger are not sated by food.

Dealing with emotional and psychological health is covered in our soon-to-be-released blueprint for a sustainable health system. In conventional, mainstream healthcare there is rarely time to hand-hold people with complex conditions sufficiently or to support them in overcoming the emotional or psychological blocks that may exist. Without addressing these blocks, or emotional health, effective behaviour change may never be possible.

Within our blueprint, and because we recognise the potential of the human body to re-establish balance, our model includes what we describe as the ‘biological terrain’ – 12 distinct, modifiable, sub-zones of health. Firmly embedded in the biological terrain are the essential aspects of emotional health.

Now please take a breather for your emotional health. Walk in the forest, connect to nature, scrunch your toes in the sand at the beach or hug someone you care about. Our emotional needs are of paramount importance too.

Comments

your voice counts

01 November 2018 at 1:08 am

Really good to read your article Meleni. This psychological area of wellness is often so ignored. I have just got back from the APS Congress in Sydney - only one presentation (out of about 8 breakout rooms over 4 days) on the connection between chronic health and mental health. But at least, there was one presentation ... and then there is dental health. Slowly, slowly ...

01 November 2018 at 4:02 pm

Wow Cate, that's really surprising and somewhat disturbing. I'd have thought they'd be all over it. You don't have to be in practice for very long to see how unmet needs drive behaviour patterns and ultimately health and wellbeing. When your heart and your head are in sync and feeling happy, everything else just seems to fall into place more easily. As long as more of us keep chipping away...

Thanks for the reminder on dental health, it's something we've not focused on much and we really ought to.

Best

Meleni

01 November 2018 at 10:38 am

It is well know anyway that the interest of the medical is not to get people into health so don't blame them anyway.

The medical do the interest of the big pharma so it is up to the individual to give the power and empower themselves

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences