Content Sections

Today being World Diabetes Day we thought it important to draw attention to some of the underlying hormonal imbalances that underpin the spiral of type 2 diabetes. Obesity and its related diseases are one the biggest threats to human health in the modern age and it's facile to say those afflicted simply haven't heard the message to eat less and exercise more. Getting on top of the over-fat epidemic isn't about helping people to feel good or bad about their bodies; body positive or negative. It’s about health and longevity and ensuring that the fabric of society continues in a self-sufficient manner to support future generations. Humans are not built to carry excess fat beyond a certain level designed for energy storage and survival. When they do, there are severe health consequences to bear.

Listen to government and health authority advice and you’ll believe being overweight is all about excess calories and willpower (or the lack thereof!). Available evidence from obesity research disagrees. There is however wide consensus that the causes are myriad and complex and that obesity and its associated diseases are largely preventable. The good news from published and clinical evidence is that for those afflicted, type 2 diabetes can often be reversed altogether assuming collateral damage is not too severe.

Once upon a time, type 2 diabetes was a rare occurrence. Now it threatens to overwhelm health systems globally. In 2017 it’s estimated that 425 million adults globally, aged 20-79 years, were living with diabetes (type 1 and type 2). More shocking are estimates that by 2045 this is set to rise to 625 million. Of these, 90% of all cases of diabetes are type 2 – again, almost entirely preventable.

Speak to most conventional authorities and they’ll tell you the cause is too much sugar in the bloodstream causing insulin resistance. In reality, it’s far from being that simple.

Hormones: drivers of change

Behind visible and internal symptoms created by metabolic disruption lie multiple, upstream, causative factors. Ranging from early and childhood trauma, too much stress, poor sleep, social (and nature) disconnection and exposure to too many environmental toxins, to the ultra-processed, sugar and refined vegetable fat-laden foods that are now ever-present. Designed to hit the 'bliss point', these calorie-dense, sugary, fatty foods speak to our primordial survival hormones, keeping us wanting more and pretending to comfort our unmet needs.

The reasons so many of us are getting fat, sick and tired are not the same for everyone. There may be a genetic and epigenetic element, but our gene expression is in turn greatly affected by our behaviour. That includes what, when and how we eat; when and how we move; when and how we respond to and recover from stress and our environmental toxin burden. And each of these actions drives – and is driven by – our gene expression, our biochemistry and our hormones.

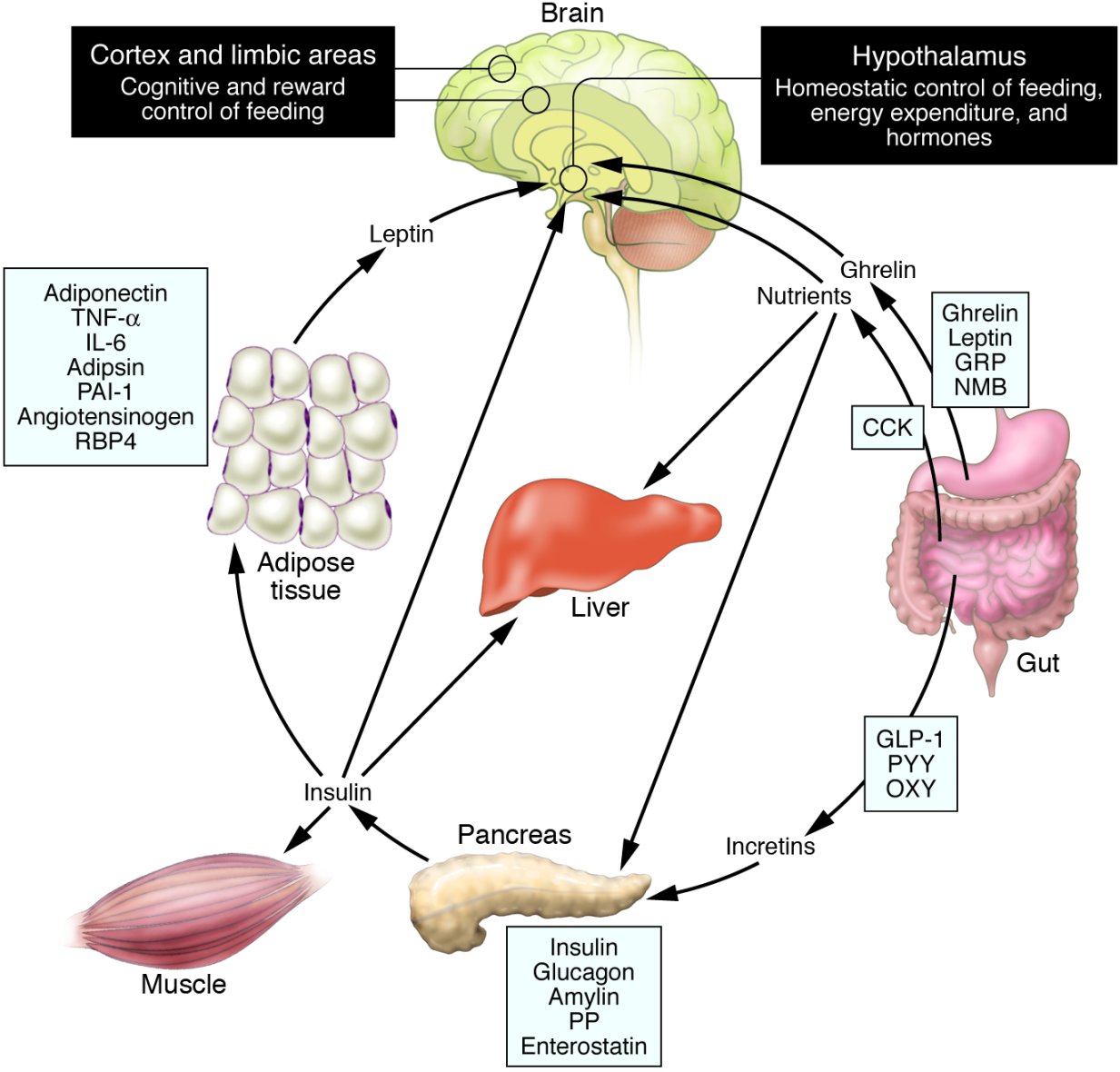

Key hormonal drivers for appetite management

We still have a lot to learn about the hormones that regulate appetite and food intake. Insulin is the key hormone released from the pancreas that determines how much blood sugar will be allowed into cells where it can be used by mitochondria to produce energy. If the sugar is not burned, it's converted to fat. We know the consequences of becoming insulin resistant - our blood sugar starts going up and then it's all downhill towards type 2 diabetes. But insulin also has other effects, with insulin receptors being widely distributed throughout the central nervous system and insulin playing an important role, in particular in concert with glucagon (see below), to regulate blood sugar, as well as energy storage or use.

Our appetite hormones are responsible for telling the brain when to eat and when to stop. These hormones are so intimately involved with our evolutionary development that they can be regarded as primordial drivers. When correct signalling stops working as intended, the dysregulation can predispose you to gaining weight, becoming insulin resistant and heightening your risk of developing type 2 diabetes amongst many other chronic diseases.

- Leptin - is a peptide, but it functions like a hormone. It’s often called the ‘satiety hormone’ and regulates the size of the adipose (fat) deposits in the body. Leptin is part of our survival response as it regulates energy intake and fat stores within a narrow margin. When fat mass decreases, the level of leptin decreases and the appetite is stimulated until fat is regained. There is also a decrease in body temperature and energy expenditure is reduced. When fat deposits increase, so do leptin levels, suppressing appetite until weight loss occurs. Interestingly, leptin also plays a role in puberty as a woman has to have sufficient fat stores if she’s to nourish a foetus and ensure the survival of the human race. When leptin levels are persistently high due to over eating, the leptin receptor becomes ‘deaf’ causing reduced sensitivity to the hormone. The absence of leptin, or the leptin receptor, leads to uncontrolled eating, therefore increasing the risk of obesity.

- Ghrelin – produced mainly by the stomach is commonly known as the ‘hunger hormone’. Whilst it stimulates appetite, increases food intake and promotes fat storage, it also does so much more, and is even involved in cancer development and metastasis.

- Peptide YY (PYY) – is secreted from cells in the GI tract. Released after eating, it helps to induce satiety and reduce appetite. Low levels lead to feelings of hunger and enhance cravings

- Glucagon – works alongside insulin to control levels of glucose in the blood (blood sugar). Glucagon is released to stop blood sugar levels dropping too low (hypoglycaemia), while insulin works to regulate blood sugar from becoming too high

- Adiponectin – like leptin, is also secreted by fat cells. It plays a role in the regulation of blood glucose and helps burn fat for energy. Low levels of adiponectin have been implicated in the development of obesity and insulin resistance.

Schematic illustration of peptides secreted by the gut and adipose tissue (fat) that control energy balance.

Source: Fig 1 taken from Revisiting leptin’s role in obesity and weight loss (Ahima RS, 2008)

Leptin - resistance is futile

You would think the more fat cells a person has, the more leptin is produced and the less the desire to eat. But in the same way that insulin signalling becomes ‘muted’, the same is true of leptin - and the body becomes leptin resistant. Even with a hefty load of fuel on-board (as food or stored fat) , the brain doesn’t get a clear signal and in turn thinks the body is starving.

The body ignores this 'ample food on-board' message and the brain sends out messages to:

- Eat more to top up our reserves so we don’t starve, and

- Conserve energy, by becoming more sedentary

Hence the leptin resistant individual is unable to eat less and exercise more, despite the repeated calls from governments and health authorities that this is the way to solve the metabolic crisis facing us. In fact, the words ‘leptin’ or ‘hormone’ don’t appear even once in the UK’s new prevention plan which Rob Verkerk PhD pulls apart in his Founder’s Blog today. For the avoidance of doubt, eating more and exercising less is not the only root cause of weight gain, but it is a direct consequence of leptin resistance and disrupted hormones which are implicated in obesity and the development of type 2 diabetes.

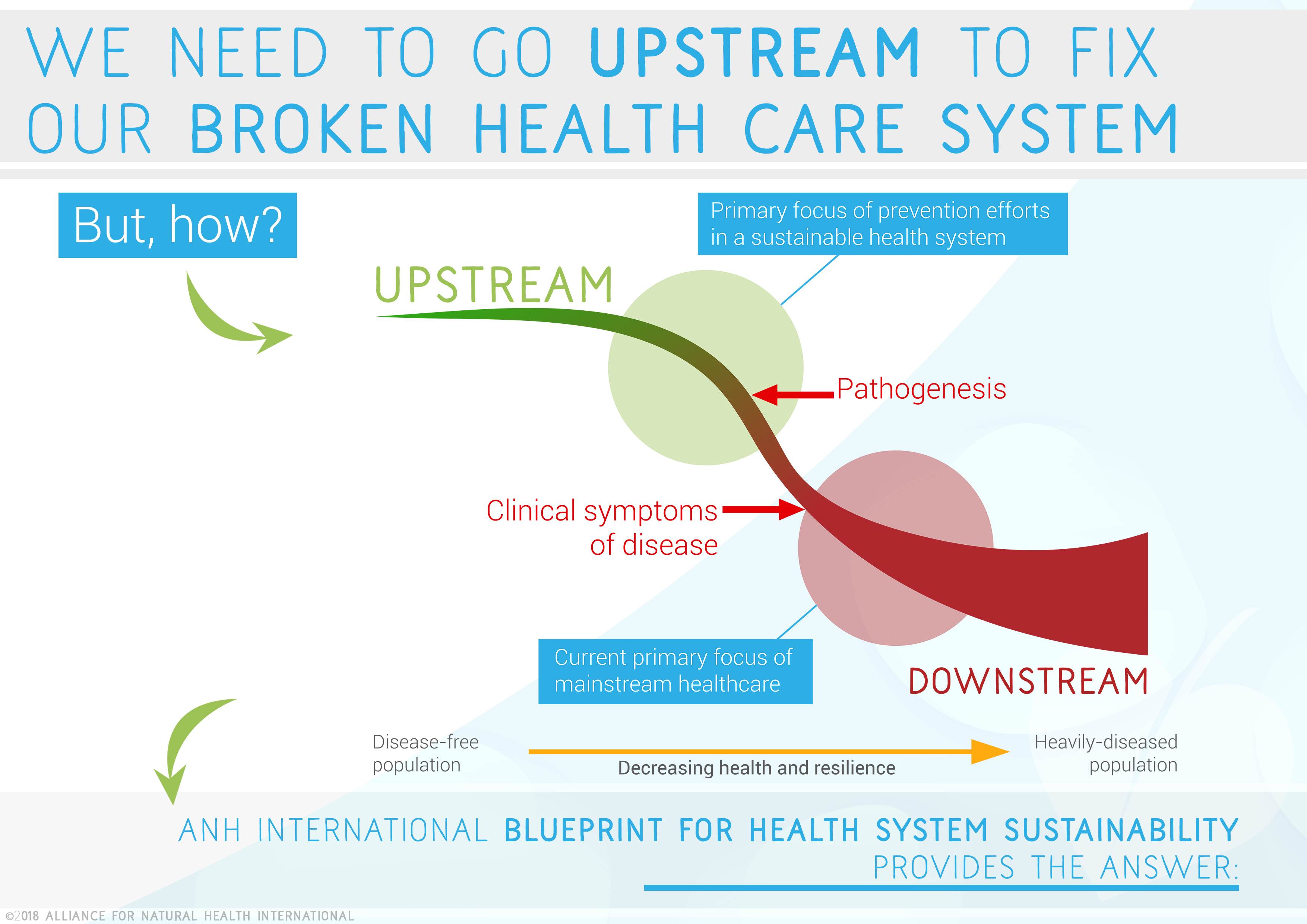

The drug-free fix

The fix is not merely down to diet alone. The fix is about recognising that there are multiple upstream causes that have created a situation in which metabolic dysregulation has occurred. Whilst a diet closer to our evolutionary origins will certainly help, it won’t address the emotional/psychological wounds that may have contributed. Hence, any strategy for truly addressing our metabolic (obesity, type 2 diabetes, chronic disease) crisis must address the upstream causes that have caused the downstream effects. The causes, of the causes, of the causes, that are way upstream in the past.

Source: ANH-Intl "A Blueprint for Health System Sustainability in the UK" (2018) [In press]

More information to get you started on your journey to leaving calorie counting behind forever:

- Firstly, forget calorie counting and low fat diets

- The 5 magic bullets to reset your metabolic programme

- Why calorie counting just doesn’t work and how we should eat to become metabolically resilient

- ANH-Intl Food4Health guidelines for adults and children to help you eat in a more evolutionary-rational way for health creation and disease prevention.

- Watch the Obesity Fix: Part 1 and 2 below:

Comments

your voice counts

15 November 2018 at 5:00 am

..Whilst a diet closer to our evolutionary origins.. back to the Mainstream's nonsensical chimp to Lucy which magically: lost a vertebrae to walk upright, lost 50% of muscle strength, changed body hair location, started to sweat instead of pant and could no longer swallow and breathe at the same time. Lucy then we are informed travellled 10s of 1000s of Kms to become Oriental with different body proportions, writing, culture and psyche, and.. Indian, Scandinavian etc.

Why not admit that humankind ib this Dern Universe is billions of years old and that all humans on Earth today come fro the far reaches of this Universe? Data from theyfly.com.. for the open minded.

And why is there no mention of the fact that diabetes 2 is reversed in 2 weeks with a zero grain and zero diet?

Looking forward to my comment being deleted as usual. Thanks. Dr V.

15 November 2018 at 8:21 pm

Please will someone in a position of influence (politics/medicine/healthcare) shout from the roof-tops the real and underlying cause of diabetes 2 and pre-diabetes. It is the ancient illness that we will sadly never find a cure for - it's called Ignorance & Apathy! As mentioned in our previous post, only the consumer has the power to reduce these shocking statistics. It may surprise some of you to learn that in the UK today, around 25% of ALL households do not have a working smoke alarm! And how many news stories do we need to read that children have died in their beds from a fire. This is madness! Why is this comparatively wealthy and well educated Nation of ours so stupid?

17 November 2018 at 3:36 am

Hi Thomas - yes - it's interesting that the theory that humans have been 'engineered' in some way by ET life has not become more widely accepted given the various elements of evidence available. Religion and political control have something to do with that. Just like avoiding telling the public at large that type 2 diabetes is fully reversible in most instances. We have written extensively on the subject, and are engaged in a lot of direct education on the subject. I'm in Asia as I write this, lecturing on that very subject. I'm not aware of any of your comments being deleted, but will ask my team. There's generally only two types of comments we won't publish: those that are commercial in nature and seek to advertise products or services (we are a non-profit), and those that are disrespectful of others. Thanks for the links to Billy Meier's site - some interesting stuff that echoes many spiritual and progressive teachings throughout the ages. Best, Rob

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences