Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD, founder, executive and scientific director, ANH-Intl

Coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2, that causes Covid-19 or just plain old ‘coronavirus’ – call it what you like – has taken the world by storm. Humans in every corner of the globe are coming together to ostensibly minimise human tragedy, suffering and hardship linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by the new circulating virus. Unwittingly, some of these efforts, especially if maintained too long or timed incorrectly, might actually be counterproductive to the interests of society. Governments, corporations, transportation companies, schools, the entertainment and sporting sectors – mostly everyone – have accepted that in the absence of a silver, pharmaceutical bullet against this novel viral infective agent, we must accept the cost of the economic impacts caused by our efforts in trying to contain and control transmission.

-

Find related articles, information and videos in our Covid Zone

One positive outcome of the outbreak is the sense of cooperation that has been enabled. Citizens, regardless of geographic borders or background, can contribute, in the words of Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), “to protect themselves, to protect others, whether in the home, the community, the healthcare system, the workplace or the transport system.”

But have health authorities, governments and corporations got enough information and context to be making the decisions they are making, often on our behalf? What are we not being told that we should be told?

Many healthcare professionals working in the natural health or integrative medicine sectors with whom we’ve spoken over the last month or so, like us, feel that context has been sorely missing in the public dialogue on the coronavirus outbreak. As has been comprehensive and relevant advice, especially for older people who are more susceptible, on supporting the immune system (see our separate piece on natural immune support) in the event of infection.

In this special report, released the day after the WHO upgraded the outbreak’s status from epidemic to pandemic, I have attempted to highlight some of the anomalies and problems around the publicly available information, and, just as importantly, identify where key data gaps lie. We hope you’ll find it provides some additional and helpful context to the information that’s being delivered by the mainstream media.

WHO declares pandemic status of Covid-19

Before we kick off proper, if you want to gen up on some basics, albeit from a largely scientific perspective, the following links give you something of a starting point:

- Comparison of Covid-19 and flu by Johns Hopkins

- Key features of Covid-19 outbreak

- Epidemiology and pathogenesis of the Covid-19 outbreak

- Our World in Data – looking at the numbers behind the outbreak

If you already need some light relief, here’s a couple of tidbits of trivia:

- Coronaviruses get their name from the Latin word ‘corona’, which means ‘crown’ or ‘halo’. When you look at them through a 2D transmission electron microscope you see what looks something like a crown comprised of the club-shaped spikes that cover the surface around the virus particles

- Did you know that around 20% of all instances of the common cold are caused by coronaviruses? Unsurprising therefore that most of the symptoms of COVID-19 are something like a common cold

- There’s nothing new about this family of viruses that have co-existed with animals and humans for millennia. This one is called novel because it’s the first time it’s been found in humans. No one can be sure about the origins of the virus, but among the more supported theories is that it jumped from bats to pangolins to humans, where it turned up in the wet market of Wuhan in the Hubei province of China. While the origins remain unclear, there are of course fertile grounds for conspiracy theories. Among them was a view expressed by former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who sent a letter to the United Nations stating the virus was “a new weapon for establishing and/or maintaining [the] political and economic upper hand in the global arena.”

WHO said?

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at the WHO referred to a “sombre moment” as the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 passed 100,000 in 100 countries over the weekend.

As of yesterday, based on data from Johns Hopkins’ Covid-19 tracker, 87% of cases so far have occurred in just 4 countries (China, Italy, Iran and Korea; see Category 1 countries/areas).

According to the WHO, of the 80,000 reported cases in China, 70% have already fully recovered.

Distribution of cases outside Mainland China as of 11 March 2020. Source: Worldometer

Total serious and critical cases as of 11 March 2020. Source: Worldometer

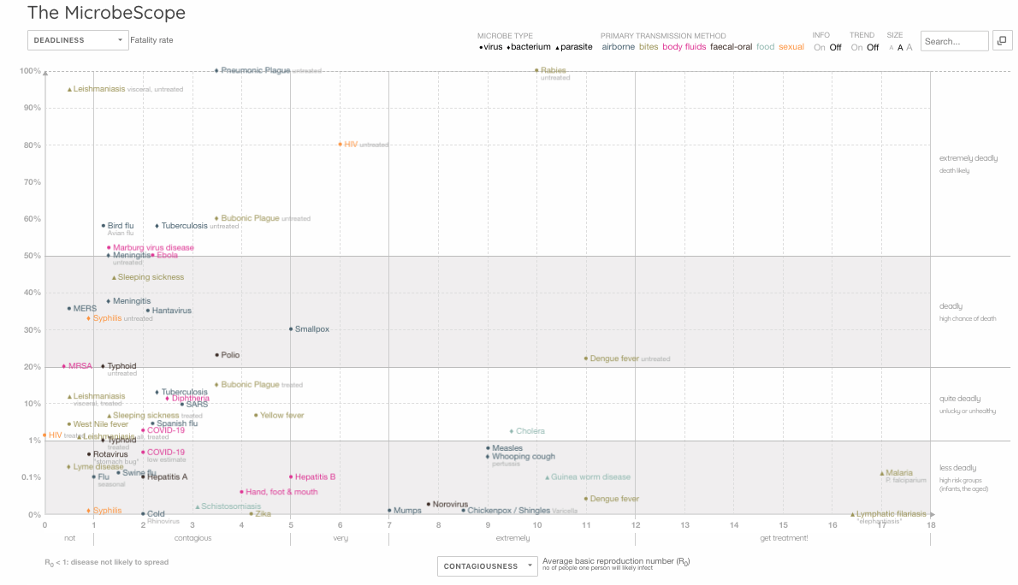

Context by comparison with other infectious diseases

One way of getting context on Covid-19 is to compare the rate of contagiousness (the average basic reproduction number (R0) which is the number of people one person will likely infect) with the case fatality rate (CFR), against other important infectious diseases. This way of looking at the infection makes sense because the Covid-19 outbreak is so recent, while other infectious agents like seasonal flu (caused mostly by influenza A/H1N1 viruses) or ‘swine flu’ (A/H1N1pdm09) have been circulating considerably longer.

One such comparison has been carried out through an interactive graphic called the MicrobeScope (see below) on the Information is Beautiful website. You’ll see data for Covid-19 sitting in the bottom left corner, with moderate contagiousness and relatively low fatality rate (presently around 1-2% of those infected). It’s somewhat higher in Italy (5%), probably because many of those infected have been elderly with comorbidities (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, etc.) so are therefore more susceptible.

You’ll also see, so far, SARS-CoV-2 appears very much less contagious than the mosquito vectored diseases, malaria or dengue fever. It is also much less deadly than tuberculosis, Ebola, meningitis or bird flu, while being slightly more deadly – based on just the first 10 weeks of available data – than seasonal flu.

Link to interactive version of MicrobeScope.

We also need to keep the numbers infected so far in context with those affected by other infectious diseases. Following is a comparison of COVID-19 with 4 other infectious diseases, bearing in mind Covid-19 has reportedly only been circulating for a little over two months:

|

Infectious agent |

Estimated annual new cases |

Estimated related deaths |

Source |

|

Covid-19 |

113,703* |

4,012* |

|

|

Malaria |

228 million |

405,000 |

|

|

Tuberculosis |

~7 million |

1,491,000 |

|

|

Influenza |

3-5 million |

290,000 -650,000 |

|

|

HIV/AIDS |

~1.7 million |

770,000 |

*COVID-19 cases only from 31 December 2019 to 10 March 2020.

Other coronaviruses that caused huge public disturbances, albeit in more geographically limited areas, namely China and the Middle East, were the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) epidemics of 2002 and 2012, respectively. SARS caused just over 8,000 deaths and had a fatality rate of nearly 10% as against MERS with around 2,500 causes and 834 deaths, amounting to 34% fatality rate. These figures demonstrate just how many more people are being affected by COVID-19, but relatively, how much less harmful it appears to be too. That’s not something the mainstream media often reports in its bid to fearmonger.

Another good way of estimating infection potential is to look at the doubling rate.

Here, for ease, I suggest you look at data collated from official WHO figures by Australian investment guru, Damien Klassen on the website Nucleuswealth. It makes sense if you’re wanting people to invest that you know how a virus like Covid-19 can change market values. Looked at this way, things don’t presently look optimistic in South Korea, Italy and Iran.

Health threat

The trouble is, these bald numbers tell us only a part of the picture. They can also be misleading. When trying to size up the nature of the threat caused by the infectious agents and what priorities you should give to containment and mitigation, you really need solid answers to a lot of questions. These include knowing the age, gender and location of those who’ve died, how many people are infected (including those with and without symptoms), how long it took them to die after infection, did the infection really cause the death or was it just associated with it, what was the lag time between infection and death, what is the reproductive rate of the agent and does this change with time, what was the person’s health status at the time of infection regardless of outcomes, what was the nature and severity of any symptoms….I could go on.

There are data on only some of these parameters. Even less of it is in the public domain.

When you look at the daily stats of escalating infection rates, they tell you nothing about whether lots of these people are recovering from mild symptoms of disease, or were they dying slow, painful deaths in an ICU? Or were they at home or in remote rural areas where they couldn’t gain access to medical care?

What degree of trust can you put in official data being supplied to the WHO? Again, as Damien Klassen suggests, some data can be trusted less than others.

And just how many people out there would be positive if sampled and tested, but they haven't been tested because they have no symptoms? Take the case of the cruise ship, the Diamond Princess that was docked in Yokohama, Japan. A whopping 52% of the 621 confirmed cases onboard (322) were found to be asymptomatic – according to Japan’s Ministry of Health.

Also, are the laboratory tests being used rock solid, meaning do all positive tests mean the virus is present, and vice versa? Back to the Diamond Princess, why did one women test negative during the two weeks of testing while under quarantine on the boat, only to then be found positive when she returned home in Japan? A similar discovery was subsequently made in the cases of two Australian men.

As you delve into what little is known, and note the mass of information that isn’t, an interesting story emerges, one that is at odds with the more definitive viewpoints underpinning public health policy that are being blasted at us daily across the airwaves.

The likely high (unknown) numbers of unreported cases of infection in part explains why Dr Anthony Fauci, the head of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in his co-written editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine published on 28 February 2020 that “the case fatality rate may be considerably less than 1%”.

Remember the bird flu pandemic of 2007 caused by the H5N1 virus – or should we say, the human immune reaction to it? At its most virulent, the risk of transmission remained low, relative to many other infectious diseases. The WHO data estimates that the H5N1 avian influenza has killed 53% of those infected between 2003 and 2020, the majority of cases being in just 3 countries, namely Egypt, Indonesia and Vietnam.

However, re-analysis of available data shows that the rate might be closer to 14-33%. This change in fatality rate was linked by the study authors to 3 things: 1) many asymptomatic and mild cases might go unreported, 2) there is common under-reporting by some countries for political reasons, and 3) the virulence, in common with many viral infections, declines over time. All of these concerns apply to Covid-19.

A Chinese study published in The Lancet compared those infected by the novel avian influenza (A/H7N9) which broke out in China in 2013 and the more lethal H5N1 avian influenza virus. It looked at the location and age of infected individuals, among other things. It revealed that the median age of those infected was 62 years for H7N9 and just 26 years for H5N1. In both cases, most of those infected (71-75%) were exposed to poultry.

In Italy, which has seen the highest rate of infection outside of China, the average age of death reported by the country’s national health institute was reported as 81, the majority with underlying health problems and 72% being men.

The WHO continues to uphold the 2% case fatality rate. Prof Neil Ferguson and his team at Imperial College London estimate the case fatality rate (CFR) at half this value, 1% which is close to another assessment by a group of New Zealand experts of a CFR of 1.4% for COVID-19 cases outside China.

But there are problems with all of these estimates. Most of the data we see in peer reviewed papers, being issued by governments and health authorities and in the media are based on confirmed cases provided by national governments to the WHO. This involves cases where there has at least been the matching of viral material taken from nose and throat swabs using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).

Being at the early stage of the outbreak, there are limited data on what is happening at a given period in time. For example, if it takes a susceptible person 4 weeks to die following infection, your case-fatality data will be out of step with your infectivity data, being one month behind. The problem is exacerbated further if you have a relatively long incubation time. While varying views on incubation have been put forward, a study just published by Johns Hopkins suggests around a 5-day incubation, which is somewhat shorter than many had previously believed. However, the study also shows that 97.5% of those infected will show symptoms after 11.5 days, while around 1 in 100 will still likely develop symptoms after 14 days of active monitoring or quarantine. Given the infection capacity of Covid-19 and these figures, it’s not hard to see how easily the virus can spread exponentially.

Economic threat

Herein lies the double-edge sword delivered to us by Covid-19. The more humans enact containment and social distancing and isolation policies in an effort to slow down the contagion of the virus, the less at risk are the most vulnerable members of our society. But also, the greater is the economic impact. The sheer scale of infection makes it a problem.

Very important decision need to be made now, especially in countries in which the virus has arrived, but has yet to become endemic. Policies to ensure social distancing, such as school closures, and probably even more importantly, care home visitations, need to be considered with great care, being informed by all the relevant, available epidemiological data. Given the typical 5-10 day incubation period of the virus and its droplet transmission mechanism, short intense action early one may in fact be preferable to delayed actions that would need to be maintained for longer.

SARS, caused by anther coronavirus, had a significantly higher case fatality rate, but much lower rates of infection. It killed only 813 people in total but caused a 2% fall in GDP in China where all but two cases occurred.

The scale of the current threat means big pledges are being made. The “international community” has asked for US$675 million to help protect states with weaker health systems as part of the WHO Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan.

The Gates Foundation have launched funding to identify COVID-19 treatments in conjunction with Wellcome and Mastercard, with US$125 million being made available.

The UN has released US$15 million from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) to help fund global efforts to contain the Covid-19 virus.

But all this pales into insignificance when you look at the potential impacts on certain industries and economies. One sector that will be hit particularly hard by shutdowns and social isolation policies is the airline industry. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) suggests that as much as US$113 billion might be lost by the airline industry in 2020 alone. While it might be better for the environment, it’s not good for those who benefit from the services provided by the airline industry in linking up the world’s economies.

Back in 2003, SARS cost the world US$40 billion in 6 months. How much more will COVID-19 cost?

Pharma solutions in the pipeline?

No drugs have been proven effective against the virus.

A vaccine is being developed, but Dr. Anthony Fauci (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) said it will likely take 12 months before a vaccine is ready for the public, having clashed with US President Donald Trump who said he wanted the vaccine ready in just 2 months.

Gilead Science’s remdesivir is an antiviral drug originally developed against Ebola, which has found use against infections by Marburg and other RNA-stranded viruses. It is currently being trialled in China. It was administered to a US patient on “compassionate grounds” and the patient, whose condition was worsening prior to the drug being given, recovered quickly.

There is a significant risk that mutations by SARS-CoV-2 could lead to resistance to antiviral agents if they were to be used at scale, as occurred with neuraminidase inhibitors like oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) used against seasonal A(H1N1) viral infections.

Useful videos

Prof Neil Ferguson and Prof Christl Donnely (Imperial College London, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis) on current status of Covid-19, containment, and non-pharmaceutical interventions

Dr Seema Yasmin on COVID-19, personal protection and pandemics

Do’s and Don’ts

IMPORTANT NOTICE

The information below is for informational and educational purposes only, and should not be construed as medical advice. If you are experiencing any symptoms of illness, or consider that you might have been exposed to the coronavirus, follow the advice of your health authority [the UK's NHS advice is fairly detailed and useful wherever you may live]. This will typically mean staying at home and avoiding close contact with other people. Do not go to a GP surgery, pharmacy or hospital and, in the UK, use the NHS 111 coronavirus service to get advice on what to do.

As SARS-CoV-2 is another coronavirus, similar to the type that causes 20% of cases of common cold, the same basic hygiene and sanitation requirements apply and, apart from making sure your immune system is in peak condition to deal with any threats, is your best form of prevention.

The virus is transmitted by droplets or contact.

So, following the CDC non-pharmaceutical advisory makes a lot of sense:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds, and help young children do the same.

- Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when you cough or sneeze, then throw the tissue in the trash.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Avoid close contact, such as kissing, or sharing cups or eating utensils, with sick people.

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as toys and doorknobs.

Add to that the NHS guidance, which has only two items in common with the CDC advice (see brackets):

- (wash your hands with soap and water often – do this for at least 20 seconds)

- always wash your hands when you get home or into work

- use hand sanitiser gel if soap and water are not available

- (cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or your sleeve (not your hands) when you cough or sneeze)

- put used tissues in the bin straight away and wash your hands afterwards

- try to avoid close contact with people who are unwell

The don’ts are clearly spelled out by the NHS: “do not touch your eyes, nose or mouth if your hands are not clean”. So there’s a real possibility that if you use a disposable mask, especially a next-to-useless dust mask, you’ll increase, not decrease your risk of infection.

Taking this advice from the CDC and NHS into account, as well as the overall picture of the threat both from infection and from our efforts to mitigate infection, it’s not difficult to consider many reactions to Covid-19 as an over-reaction.

OK – if we’re talking about a very large public meeting for the over-70s in a country or region with known infection by the virus, stop the meeting. Some golf clubs and Bingo halls might be affected, but it won’t bring economies to a standstill. Otherwise, let people get on with their lives, cognisant of the hygiene and sanitation measures. We must also demand more transparency in the reporting.

So keep an eye on the stats, and we’re finding there’s more relevant data delivered daily by Worldometer than there is by the WHO itself.

What the data so far suggest to us is that the vast majority of people (>97%) will be fine, even with infection. Most people will at most have mild symptoms that are not very different from the closely related common cold. Efforts should be made, just as is the case routinely with flu, to in particular protect the most vulnerable groups, especially older people with underlying conditions.

On balance, at the time of writing, social distancing appears to be the most powerful weapon we have.

Conclusions

Covid-19 has now achieved pandemic status. That label generates fear. Yet the decision is based on geography, not biology. So while some estimates suggest two-thirds of the global population will become infected, for many this might just involve a ‘sniffle and a tickle’ – or be entirely without symptoms.

We shouldn't forget that a new virus using the human species as its host is something entirely natural. We will adjust to it - and this new coronavirus, from wherever it originated, will make its home in many of our bodies, and our immune systems will become more resilient as a result.

As stated by the WHO’s Director-General, Tedros Ghebreyesus, “it would be the first pandemic in history that could be controlled”. More importantly, perhaps being something worth celebrating, this could be achieved largely without pharmaceuticals or vaccines – just human cooperation around containment and control.

The way things are currently looking, in our view, the biggest cost of the pandemic will not be through suffering and illness caused by direct infection. The greatest costs will be the economic and social consequences of our efforts to combat the virus. It is not just drugs that have side effects.

In order to minimise this impact, employers, event managers, transportation companies, health authorities and all those responsible for how those they communicate with behave, need to think things threw very carefully. Careful consideration, not panic or knee-jerking, will be the way forward.

I found myself resonating with the commentary in the BMJ offered by Dr Peter Gøtzsche, expelled co-founder of the Cochrane Collaboration and founder of the Institute for Scientific Freedom in Copenhagen. So, let’s finish with Dr Gøtzsche’s words as he explores the notion of us being potential “victims of mass panic”.

He asks:

“Why all the panic? Is it evidence-based healthcare to close schools and universities, cancel flights and meetings, forbid travel, and to isolate people wherever they happen to fall ill? In Denmark, the government recommends cancellation of events with over 1000 participants. When some organisers crept just below 1000, they were attacked by professors in virology and microbiology. But if it is wrong to invite 990 people, it should also be wrong to invite 980, and so forth. Where does this stop? And should big shopping centres be closed, too?”

Comments

your voice counts

12 March 2020 at 6:18 pm

The media have poured contempt on Chinese trying to avoid the risk by eating Garlic soup yet no mention of the fact that Garlic is only to some degree effective if eaten raw. During the second world war Garlic was known as 'Russian Penicillin' it was all they had. The eating of raw Garlic by those who buried the bodies at the time of the Black death was said to give significant protection, no mention of this now why? Traditionaly in China health workers eat soup made of dry ginger and other herbs that are believed to have at least some protective effect in the face of viral epidemics, this is being reported on line in China now but we hear nothing of this. Why? People are urged to have injections to prevent mumps but is only 70% effective for adults, if a herbal product is only 70% effective the big drug companies would widely broadcast this as a put down . Seems to me the malevolent profit driven agenda of big farm can be seen so often. Try buying iodine in a UK pharmacy once a universal cure all, I could not find any had to buy on line, A Chemist told me with a smile we have patented alternatives to iodine that is why we do not offer it.

13 March 2020 at 10:19 am

Yes Tony - thanks for your comment. The absence of information o fwhat citizens - especially older people - can do to help make their immune systems more robust is startling, yet predictable. We've released another piece yesterday on simple ways in which people can enhance immune resilience.

12 March 2020 at 6:23 pm

Martin Paul predicted this outcome from 5G which IS rolled out in China 130,000 5G antennas South Korea 75,000 America 10, 000

Exposing yourself to EMFs Dirty Electricity and radiation from wireless kills all life!

12 March 2020 at 7:14 pm

While sanitising your hands and not touching your face is the sum total of Gov and NHS advice or wisdom, I am frustrated that no Dr or NHS dietician has come out with even better advice and told every one to build up their immune systems with Vit C and D3. This should our 1st priority given that covid 19 causes inflammation of the respiratory system and both Vit C and Vit D3 are anti-viral.

why wait 12 months for a vaccine when you have a risk free option in front of you.

The latest news is that the uk Gov are willing to infect people with corona virus for a back hander of £3,500 who mad is that.!!

13 March 2020 at 10:29 am

We agree with you Nigel - the medics and health authorities have been incredibly remiss in not giving more science-based advice on immune support. One of the problems is that the relatively few doctors who are informed on such things are always concerned that what they say might be used against them by licensing bodies - and their views might get lost among those of rogues who're trying to seize the opportunity and pedal potions that have no immune modulating effects.

17 March 2020 at 11:35 pm

Yes, Nigel, both Vit C and Vit D3 are anti-viral. But I think is is also very important for EVERYONE to understand that there are, especially now, many bogus voices around who strive to distract the public from the value of vitamin C therapy because there are dark forces behind it all -- Pauling's VALID work with vitamin C supplementation has been "falsified" by data distortions and lies, and he as a person (a double Nobel laureate) has been slandered as some deluded idiot by the criminal medical establishment and its countless quackwatch shills, lackeys, ignoramuses, and trolls for decades and it continues today (read the well referenced scholarly article titled "2 Big Lies: No Vitamin Benefits & Supplements Are Very Dangerous" by a published author of the Orthomolecular Medicine News organization).

But you can't discredit the facts with lies. That only exposes and discredits the liars (see cited reference above).

26 March 2020 at 10:44 pm

I would like to second and underline Nigel and Albert's comments on the long history and medically documented value of IV vitamin C in megadoses, that was actually used in China this year. By merely decreasing the dosage used in a study and or limiting the time the vitamin is used, an author can get the results he wants. Then contact the newsmedia to run the story headline that Vitamin X doe not work-see. But the worst part is the fear/and or ignorance of the media that the FCC will come down on them for being a "public health danger" by reporting a truthful but unorthodox therapy that competes with big pharma products that have bad side effects.

19 March 2020 at 2:31 am

I totally agree. The AMA doen't "recognize any "treatments" other than toxic, sometimes deadly, drugs! Yet, we've known for centures about natural treatments and the NECESSITY for proper nutrition, including supplementation. Yet, NOT a WORD about taking extra C, D, E, selinium, garlic, collodial silver (that always gets boo-hoo'd even though there are NUMEROUS studies on its effectiveness against bacteria and viruses. (I made another batch today). Good luck everyone, don't forget your neighborhood herbalist and homeopath. We'll make it through together, without the AMA/FDA !

13 March 2020 at 10:18 am

Strange times indeed.

We act or react according to our beliefs.

The thing about fear is that it operates as belief but without any conscious evaluation.

The thing with leveraged fear is where what we already fear and believe but haven't truly and consciously reevaluated operates as a consensus reality of social contagion.

No one in mainstream asks real questions or challenges the dictate. Mainstream is the idea of herd immunity of collective compliance and conformity as if the herd is being wisely or indeed expertly guided by the only ones who know.

As a result of my own process of education, both moral and scientific, I don't accept the official and socially reinforced germ theory as valid or complete, but see other causes for the body's episodes of inflammation, detoxification and rebalancing - that are feared and attacked as disease when they are symptom of health activating under duress. The causes I see are more of toxicity of both physical and psychic-emotional nature.

Psychological defences operate forms of dissociation and denial, such that conflict instead of finding resolution, can be diverted and stored in the body - and in the body politic, so as to hold patterns of definition and control whereby energies of attention and funding are diverted to a displacement mapping of a sense of self protection fuelled by both fear and grievance and beneath which are terror and rage along with heartbreak and impotence.

This 'control' agenda runs in our name as the cover story for separation and conflict trauma of which we are mostly set over and against so as to see it Out There rather than address the cause within our own heart and mind - of conscious decision. In that sense it runs as LIKE to a parasite that progressively usurps our own natural functions - such as to invoke the protective power of love as a means to induce self-destructive and loveless sacrifice.

The split mind that runs under narrative control - or identified in 'story' is literally cast out in dramatic polarisations that effectively pre-empt and deny relational dialogue, such that any critical awareness of the narrative structure, is only accepted if promising to reinforce and support it, while all else becomes 'hate-crime', 'denialism', and a socially legitimised target OF hateful denial under claim to moral authority backed by vested interests of state and corporate controls - who also set the propaganda that frames the narrative by every trick of persuasion and deceit. And whose 'mainstream' model of spin becomes an entity or world in itself, set around an insider view that runs knowingly as protection of the system and not of the living.

The idea of systems can be helpful when allowed to serve and support living systems which are of Open Communication and not closed conceptual programming. Control thinking is always closed system of the overriding and substitution of the heart of listening and bring forth from true with-ness that which is truly worthy. There is no truth or love in technologism, nor in the capture of it for private agenda.

That evils or false premise given power leads to its own destruction is the opportunity to disengage from them when they are recognised to run counter to their belief.

There is absolutely no doubt that the idea of contagion operates in the mind as fear or lack-driven identity and response. Going viral for social media or setting the memes and fashions of thinking for narrative framing or social engineering. The hard and precise evidence for physical contagion is less solid - but is so deeply established as to shape the mind to it as established fact.

Toxicology is very much anthropogenic in large part. Toxic debt is part and parcel of 'control agenda' and a false economy that demands the sacrifice of the living to ensure its own systemic sustainability.

Control thinking is released to a true decision rising from honouring and honest communication - within - as without. I am not seeking to add yet another layer of 'demonisation' to an already insane defence complex.

Alignment in health is not the result of 'all the king’s horses and all the king’s men' - but a releasing of toxic psycho-physical baggage to a rising awareness of wholeness of connected being. This is not instead of the modalities or methods of caring, and seeking help in restoring vitality and function, but is the context without which only a management of sickness, conflict or debt can operate in our Name.

Until we can stand in our own 'No!' or 'Thanks - but no thanks!' - we will not uncover the power of a true acceptance and alignment in our being. This 'No' is not reactive, grievance driven or fearful, but honours integrity of being in holding a consciously communicated boundary for the freedom of being ourselves - without denying that freedom to another.

13 March 2020 at 10:38 am

Thanks for this long and considered comment, Brian. We agree with a large part of your thesis. Our interaction between ourselves and billions of microorganisms is not only a completely natural process, it is essential to who we are and what we are. Viruses are part of our inner and outer microbiota. The moment in our history at which a new variant of a virus finds a home in its new, human host species could be viewed as a time for celebration, not one warranting panic. Our immune systems will ultimately strengthen, not weaken, as a result of our exposure. This particular coronavirus has a lot more in common with the coronavirus that's responsible for the common cold than it does to SARS or MERS. We're just acquiring a new kind of cold, and yes, vulnerable, older people will remain vulnerable. Why don't we do more to help them become less vulnerable by helping them to strengthen their immune responses?

14 March 2020 at 4:18 pm

“It may shock you to know that all the world’s bacteria have access to a single gene pool, which has provided an immense resource for adaptation, manifesting an array of breathtaking combinations and re-combinations for three billion years! Any bacterium—at any time—has the ability to use accessory genes, provided by other strains, which permits it to function in ways its own DNA may not cover. The global trading of genes through DNA re-combinations provides for almost endless adaptation possibilities. Therefore, what has been done to one has been done to all. Widespread use of antibacterial agents is both futile and disastrous. Future life sciences and medicine will comprehend the more effective use of agents to stimulate positive adaptation of bacteria resulting in chains of supportive symbiosis. In the presence of love, these positive adaptations naturally occur. In the presence of hatred and fear, negative and resistant strains of bacteria are more likely. Life forms are ever changing, and yet the basic chemistry of life remains the same. Do not cling to forms that are passing, but seek for an understanding of life that embraces and includes all possibilities. This is accomplished through integrating and expanding patterns and relationships. In this way, you will see God as the creative power of life. When I asked that you love one another, I was not just giving you a recipe for human fellowship. This is the doorway to life eternal.”

(The Keys of Jeshua - Glenda Green)

As for a ‘new virus’ - Science has hardly begun to scratch the surface of the complex realm of microbiota.

Currently reading 'Fear of the Invisible' by Janine Roberts - which lifts the curtain somewhat to reveal some of what is presented authoritatively as part of Corporate and Gov PR rather than reveal the process of science in act and its context in terms of insider interests, funding and control of the narrative - perhaps with good intentions.

Science looks at the very very small, indirectly - by means that introduce artefacts or break out of living context in order to 'see' - and then seek to define in terms of linear cause and effect as if each particle has agency - rather than operating a matrix of fluid probabilities - through which a living Field aligns and expresses functional expression.

You end with a question.

Is it rhetorical?

I had written in response but now sense it is a question in terms of a plea. In the same manner as Tessa Jowel made plea in the House of Lords shortly before her death. But to WHO exactly?

Or is WHO the right answer - a globally managed medical model that operates more in terms of a protecting a corporate control against checks and balances of transparency and accountability?

When I say the system cannot afford to let light into closed control system, I am not talking about money or capacity to direct funding support. There is a lack of substance that has to be protected from exposure by all and any means, and this commonly false flags the frailty or unsustainability of toxic consequence to a cover story that can instead become a focus of fear and the attempt to 'deal with' , eradicate, attack or control it. This is no less true of the conflicted-mind seeking to displace its conflict to the body or the world or the 'other'.

If we knew that which we do, we would no longer be able to do it. And would WANT to uncover truth as a basis for finding healing of fear and conflict as a perspective and awakened purpose that naturally aligns compassionately.

In terms of taking your question as a question:

Because (in general terms) our definitions of health and sickness are reversed - with fear and distrust given to life and faith given to medical interventions of life as weakness and conflict that must be managed or it will fail. How could this not conflict us and make as ever more dependent? There are points where life and interventions are one - so it is not just a matter of the forms things take - but of their underlying purpose.

Why do we not extend and embody practical love - as nursing, nutrition and solidarity of support?

Is it not because this has been ruled out by being regulated in as tickboxes and targets to replace teamwork, trust and an espirit de corps?

The system has the disadvantage of being both the answer to a call for help AND the marketing and management of our attempts to evade our responsibilities by seeking panacea for problems that are not actually chemically addressed and this brings all sorts of psychic-emotional expectation and demand into the willingness to pretend or presume to be able to meet - and manage such demands.

Helplessness in the face of the suffering of others is very hard to bear. Where do we begin? When our very system is set up to block any real change - and this can even be found in the regulatory structures of an collective or institutional willingness TO change.

The extension of love is the willingness to recognise and receive it - and this is not something to wait for the idea conditions to arrive. Though we can deceive ourselves, a tangible love is recognisable and workable within the current conditions. Love is the capacity to look on fear so as to look past it. I feel we are collectively learning about love by generating such an experience of its lack or absence. Without love we have nothing - and so I am not using it sentimentally or as manipulative virtue signal - but as the basis of supporting us through even great challenge.

Can we love truth enough to say or act our 'No' to that which we now recognise undermines our integrity or the integrity of others - and in a way that actually supports a social or cultural integrity - rather than coded mores of conflict avoidance?

By withdrawing faith and allegiance from old habits or acquired patterns of thought and behaviour, and learning step by step to grow a new expression. If corruption operates decay and destruction, cultural renewal expresses then will to live - and this is often greatly challenging to who or what we think we ourselves and world to be - so as to need a unified or whole commitment that comes naturally from the experience of health and wholeness.

The virus panic may be used by many agendas, one of which is the intent to re-prime fear based medical management under greater (globally orchestrated) controls that I associate with mandatory 'medical' experimentation on human beings without their informed consent. Which is already documented as part of the way a loveless science seeks control. Fear HAS to seek control, but love is the power of aligned purpose in decision - and this act is the way of undoing fear - and in a sense transforming the energy it took into positive or integrative embodiment.

17 March 2020 at 11:57 pm

China has been conducting clinical trials using high dose IV Vitamin C that helps treat people that are severely affected. China recommends using it to treat COVID 19. South Korea is also using it. It can save lives, but there is no profit for Big Pharma, so I doubt it will be used in the US.

18 March 2020 at 10:59 am

I am not making any firm statements, not being a physician, but I am a critical thinker and believe more people should be thinking critically in life itself. I have questions about this virus that I believe need to be researched and disclosed, if my hunch proves to be correct..

My questions are:

A) If the body's immune cells memorize or recognize bugs they have fought off before, then why is there seemingly a complete absence of herd immunity to this virus?

B) That being the case, why is it so particularly contagious?

C) In fact in absence of lab tests, how do we know the contagion rates accurately? Are the reports accurate?

D) Given all of the above, I ask: Could this virus be genetically engineered?

Conspiracy theory? Come on. We live in the days of genetic engineering, which is being practiced widely on food, clothing materials, and more. It is a big business. Can't we see it, and don't we see it? Once again, come on. Time for a think!

It is only logical during this time, when people love to make a giant profit, that they forgo all ethic and will go to great lengths to make a big buck.

Let's face it, to get into public office requires being bought off from the ground up. Politicians become compromised. They support their patrons. And further, they may even believe the stories they are being told, themselves not thinking critically. They too may think they are doing good. They may be very wrong.

I see a grand manipulation scheme afoot, for profit.

I base this not on conspiracy theory, but on medical facts and questions, above.

To circulate such a virus for any reason at all, let alone for mind control, inducing of fear and huge profits, sickening and killing people in the process, is a violent criminal act, that should be punished by class action lawsuits and jail time. Think how many people are losing work, how the economy is folding, freedom of association and American freedom at large, all are being slashed with a figurative knife. This is not funny and should be taken very seriously, as should also, the virus itself. I never said the virus is not real, did I? Precautions are important, as is supporting general health.

11 April 2020 at 11:10 pm

There is a LOT of SEEMINGLY involved in the reporting of this event.

I recommend the following site - always to a discernment. But in my view it is clear, calm and collected in its drawing attention to qualified but denied voices within the professions associated with the sciences involved.

https://swprs.org/a-swiss-doctor-on-covid-19/

As for D) - all viruses are created by living cells. They are not aliens - and are part of our cellular function as symbiotic LIFE - not self-isolated and locked down rogues - though if conditions break down the integrity of cells and thus intercellular communication, the attempt to 'survive' blind can result in growth or development against the body function. But also in prioritising under stress and challenge the body will sacrifice peripheral functions to maintain vital function - and this manifests disease symptoms too.

Having just read 'Fear of the Invisible' by Janine Roberts - which was a timely and worthy source of documented detective work, I see that even outside the bio-weapon dept - all manner of experimentation is performed on living creatures that involves taking indiscriminate (not really isolated) genetic materials from the sick, injecting and 'passaging' through them and many others to then add to some in vitro cells that have been pre-toxified or stressed and weakened and allowed to recover. If the passaged 'serum' caused these cells to 'sicken' or die - it is taken as a purified virus strain from which to culture for vaccines.

The whistle blowing discovery that an early polio vaccine caused cancer (SV40) was shut down even as it was being launched. The woman was not given any honour or recognition for her public service - but she was later recruited by the military because they were interested in how to give cancer - perhaps under the edict that if it can be done our enemies will otherwise do it to us first and we must therefore develop such means so as to also develop defences.

Just how easy it is to transmit viral infection is questionable in my opinion - but how difficult it is to undermine the belief in infection is the issue of magic and superstition. That information passes between cells is known, why would some operate on it and pass it on and others not - is in my view a matter of the terrain and cellular integrity.

Because I release the virus - and carbon dioxide - from a false flag - means I am more focused in toxicity and loss of cellular integrity - which I hold to be primary immunity - and this operates the same on the human level. Loss of integrity leaves us open to misinterpret or be misguided such as to compound the error by our own 'defences'.

Under conditions of scarcity (which may be artificially contrived by choking back supply), control can be exercised over those made dependent. And under conditions that block the communication and support of love for life - control is sought as substitution - but can never be enough because there is no substitution for love of life no matter how much is stuffed into the hole that operates instead of the wholeness as a basis From which to live.

and A) when the 'infection' is considered to be latent - as in asymptomatic carrier - you have the same scheme as HIV - in which the presence of antibody (via unreliable tests) is consider infection rather than immunity!

That this is a globalist epidemic is hardly hidden - but to date the only new thing is the organised mass panic, and the late critical and often fatal stage (which may not be the same disease) in which oxygen cannot be made by normal breathing. It isn't pneumonia (which is a bacterial effect) and yet it may be made worse by chosen, allowed or dictated treatments rather than nursed by treatments.

The corporate monopolists captured the regulators long ago - but this is a shift from covert to overt control.

I also didn't say the virus is not real - but that our reaction to it may be where the primary danger lies.

the power of the mind is made very obvious under fear, but without the corollary that the same power can as easily operate a positive or integrative reinforcement.

18 March 2020 at 11:09 am

I want to add to my comment: If a bug is said to be a "novel" virus, one that is brand new, how does a brand new virus just very suddenly and magically appear? Don't they usually evolve over eons of time?

Presumably if this was a naturally mutated bug, wouldn't it be recognized and fought off by the body? Again, why is there NO herd immunity to this bug, or so it would appear on a grand global scale?

I find the whole combination of things to be very suspicious.

Again, the illness is very real and I am neither denying nor underplaying that. Precautions are important as is good care if affected, both self care and by a physician, together.

But, is this virus being used for a particular purpose? I think it merits a lot of questioning and probing. Ah, those who want to undermine the cause for preserving their own existence, will fight this tooth and nail. They will mudsling. Eventualyl their lies will come out into the public, given good teamwork by all. IT is time for this game to be lost. Human life and wellbeing are at stake, so is the economy, so are animals, as they all have themselves, openly admitted. Do they want to go hiding the truth and covering it up? All the more proof that ill intentions are afoot and profiteering is at stake. While saviors come cloaked in the guise of righteousness and good cause, as saviors of mankind.

If my hunch that this bug is genetically engineered, w hich I believe evidence may support, then this notion of savior, could be no further from the truth.

And I hate to think this way. Even i don't enjoy this, and even i used to think such things were conspiracy theory> That very invocation is nothing more than a way to deny painful realities that if not faced and dealt with appropriately, may at least potentially, literally and figuratively on both counts, run us to our grave. This is not to be brushed aside or taken lightly, give the true circumstances at hand.

11 April 2020 at 11:58 pm

The choice of words in any PR is crafted. America was 'discovered' by europeans and called the new lands - irrespective it was already there and populated already.

The definition of a virus is a matter for the high priesthoods of inner chambers - but as I understand the novel way of doing this (ebola and Zika preceded CV2 - and this procedure was adopted for HIV after the search for 'this most elusive virus' failed).

A genetic picture is assembled or modelled from multiple fragments of code found in viral matter (that is never totally isolated from other nano biotic fragments such as prions, and of course other viruses - including all those yet to be 'discovered'.

This is then 'cloned' to see it behaves such as to be indeed the sought after and presumed viral 'cause' of a specific disease. (Mono morphism postulated each virus or bacteria is associated with one disease, while polymorphism holds that microbiota can change form to meet different functional needs - not unlike the idea that stem cells can become whatever functional cell is needed by the whole).

The test used to discern traces of the virus then looks for matching lines of code for the defined virus - these are often short sequences or fragments and may be parts of other viruses etc. The test is not quantitative and is often run many times to magnify the result - so as to see the virus from the noise in a manner of speaking. None of this proves the virus - as defined, modelled or believed - actually causes the disease condition. Just as the presence of cholesterol doesn't prove causation of athlesclerosis (damaged and blocked arteries).

In all that I have wrote I have sought a common sense understanding of a subject of infinite complexity - as a ongoing willingness and not a final destination. If believing in bio weaponry undermines my immunity - why would I want to do that? So I put it in brackets with an understanding that such belief given power can destroy a nation without a shot being fired.

All viruses are created by living cells - though this could be in vitro (in a petri dish etc).

On being brought into the cell, the protein shell is take off and the information used or perhaps left unused if not applicable - and why not stay open to a spectrum in which parts of a message may be used and others discarded?

On activating the instructions, intracellular processes are enacted - one of which may be the making of solvents to break up inorganic toxins and excrete them from the cell and eliminate from the body - and other is a re-signalling of created virus to other cells as an alert to toxic environmental exposure or stresses to the maintaining of balance between inner and outer - such is the fundamental or primary responsibility of cell as of self. And so this biosystem operates as an adaptive life support, to rebalance under environmental challenges - and because it operates extremely fast, it offers evolutionary jumps in what is to us a short span of time. In this, natural selection is a symbiotic fit arising from both quantitative and qualitative shifts and not as a selfish gene, made in our own image.

18 March 2020 at 12:45 pm

I hereby correct one poorly worded statement. When I said, to circulate such a virus is a crime that should be punishable by jail time, I meant to release it to the public, from the lab, hatched and cultivated and very possibly, if the evidence proves to be correct, one that is genetically engineered. To criminalize sickness, is itself a sickness and does not belong in our democracy. People could think they are sick with some other illness that they already had pre-existing, that flared up, or...who knows. They could be asymptomatic, not knowing they have it. Do they deserve jail? Should freedom of association be clamped down on...especially, lacking tests to even prove the validity of this widespread pandemic?

Last but not least, we don't need the government to tell us to self-isolate if we are sick. The truth is, that most people with common sense, will do so of their own accord. Carrying an asympomatic virus, is true of any other virus.

And if I understand correctly, it is not the virus itself that is so virulent, but the interactive elements of immunity with that virus, that are the more serious problem. If we keep our immune system in good shape, presumably we are at least in a better position to screen it out in the first place, and to better fight it off if infected. So is the virus itself the huge danger, or is it the interactive elements of immunity/lack thereof, with the virus, the real problem? I ask this as a question, not making a firm statement.

If this virus is genetically engineered, my concern is that there may be a mission afoot to develop vaccines for profit ,based on something we were all misled by fear to accept. If this is a product of genetic engineering, then very sinister matters are afoot. It really merits researching. And they will, guaranteed, buck and resist, deny with all of their worth, titillate, criminalize, point fingers in any way they can, to theoretically win their case. If they do so, it is frankly only more reason to be suspicious. Those who do not have something to hide, don't act in malicious ways. True?

18 March 2020 at 3:08 pm

As an over 70 year old I always take reasonable doses of vitamin D3 and vitamin C to keep colds and flu away in the winter, although it did bother me when we were away in our small motorhome last year when I caught a really bad bug that I felt was leading to pneumonia. I did not take any vitamin C or D with me as it was the edge of summer, so on returning early, I took more than usual of both and it went. Two other guys in our village had it and ended up in hospital. So I am doing the same with the coronavirus and will continue to do so. One thing I read about this virus was the under 15 year old's do not seem to get it, is this correct?.

19 March 2020 at 11:18 am

Hi Trevor

Thanks for your comment. It's great to hear you're using natural therapies to keep yourself well. You may also want to consider adding vitamin A and zinc as well to help suport your immune response. You're right that in general terms children seem to be less affected. This is probably because they're innate immune response is able to very effectively deal with the virus with less of a need for upregulation of the adaptive immune system, the over response of which leads to the severe respiratory illness more commonly seen in older people.

Wishing you all the best. Keep well.

Warm wishes

Melissa

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences