Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD, executive & scientific director, ANH-Intl

A staggering, nearly 200,000 people (191,740 to be precise) in the UK submitted responses to a consultation run by the UK’s Department of Health & Social Care, headed by the Health Secretary Matt Hancock. This torrent of responses was made during a deliberately narrow window, from 28 August to 18 September. The consultation clearly piqued people's interest, asking the public and stakeholders for views on the Government's proposed changes to UK medicines law to prepare the way for mass vaccination against Covid-19 disease and flu.

Ask and ignore

The majority of consultations get a light sprinkling of responses, typically a lot fewer than 100, often less than 20. So it’s important to get some sense of the numbers of people who saw fit to respond within this very narrow 3-week time frame. The one-fifth of a million who responded represents 0.4%, or 400 in every 100,000, of the adult population. That’s nearly 5 times all the adults who have died with (not of) Covid in the UK since the pandemic broke in March, based on official figures.

It’s also about the same case rate that the Government has declared for the UK hotspot of Liverpool – but imagine this same density spread over the entire four countries of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. We’d like to think that our ‘Say it Now, Don’t Regret it Later’ campaign had something to do with this. It was, after all, the most visible campaign alongside that of the journalist-run Mirror Project.

Last Friday (16th October), the Government released a press release saying it had “analysed the responses and considered the feedback received” . Every one of them? Somehow, we doubt it. According to the Department of Health and Social Care, It included 188,040 completed responses received through the GOV.UK page and 3,700 responses received by email.

The day before this announcement, the new regulation, entitled The Human Medicines (Coronavirus and Influenza) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 was put before Parliament without a whiff of publicity. The Government argued it was urgently needed as cases of infection of both flu and Covid start ramping up.

Given the scale of the response, you’d expect the Government to be listening keenly. So what did the Department of Health officials and our elected executive authority do with these responses? The answer: nothing. Zilch, Nada. They went ahead as if no one had objected.

Suspend democracy

But drafting legislation is one thing – getting it through Parliament is another. Unfortunately, not in this case, at this time. It turns out that democracy gets suspended when it’s likely to get in the way. Two factors work together to give the Government sweeping authoritarian powers. The first is the World Health Organization’s cavernous and controversial definition of a ‘pandemic’ that no longer requires severity or deaths to describe it. The second is the UK-specific, recently renewed Coronavirus Act 2020 that swept through Parliament almost unopposed, 330 for and only 24 against.

These two things hand the Government powers that have been described as “the biggest restriction on civil liberties in a generation”. They mean that dialogue between different scientific factions, the need to justify and be accountable for measures that decimate lives, livelihoods, education and the economy, are entirely optional.

In the case of the changes to the medicines regulations to prepare the way for mass vaccination – it was obviously decided it was best to push it into law through the back door, especially given the scale of public sentiment that we expect would have largely opposed the changes.

As the Hansard report shows, Matt Hancock’s Under Secretary of State for Health& Social Care, Jo Churchill MP, tabled the draft regulation in a written statement on 16th October – and it went flying through. No questions, no discussion, no petitions.

Breed more distrust

The real bombshells in the amended medicines law are tucked away in the legal language of the regulations. Our four top picks are as follows:

- No attempt to enforce higher levels of transparency to compensate for abbreviated testing time. The history of vaccine development is not one that is synonymous with data transparency or lack of bias. We have argued before this is a major reason why ‘vaccine confidence’ is declining, not increasing, in many regions. So how about amending the medicines regulations to overcome such issues – especially given the Covid vaccine project has been positioned as a cooperative exercise intended for the public good, including massive funding by taxpayers? We’re not so sure, especially given the lack of any attempt in the amendments to make vaccine trial data more transparent, an approach we’ve been pushing since we wrote an open letter to the UK Health Secretary in late April. A letter that remains unanswered despite reminders.

- Vaccine company reps, as originally proposed, will become the most likely ‘objective bystander’ in any court cases concerning civil liability. While manufacturers have had immunity from civil liability since 1987 if the vaccine is found to cause damage or injury to a vaccinated person, this immunity applies only if there is no evidence of negligence or defectiveness in the vaccine. Understandably, what exactly represents negligence or defectivity could end up being a key battleground for anyone trying to pursue a case for damages. It then becomes a matter of opinion to be judged by the courts. Bearing this in mind, whoever is to be the ‘reasonable person’ who will represent the view of the legally appointed ‘objective bystander’ becomes all-important.

In our own response, we strenuously advocated that such so-called ‘reasonable persons’ should not be tied to the vaccine or pharma industry as they then couldn’t possibly be objective or independent. They would be more like a ‘vested interest bystander’ than an ‘objective bystander’. As a nod to the dismay that we are sure most responses would have reflected, the Government removed reference to the pharmaceutical industry. The reference now is to a person with 'relevant expertise in the subject matter of the breach’. Different words, same thing. We’re not impressed by this kind of lip service, Mr Hancock. - Drug and vaccine advertising is re-legitimised. This change will allow direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs or vaccines for the first time in the UK (or existing members of the European Union) in over half a century. This will be applied to one or more unlicensed Covid-19 vaccines, vaccines for which the true safety and effectiveness will likely still be unclear because of the unprecedented expedition of the roll-out. One thing is to get the numbers required to conduct Phase I, II and III clinical trials within a concertinaed time frame, all of which gives the Government justification to say that while the vaccine is ‘unregistered’ it is not ‘untested’. But it’s quite another thing to not have sufficient passage of time (years, not months) to be able to observe the possible manifestation of longer term effects (e.g. certain autoimmune, nervous system and other systemic effects) that have shown up with other vaccines only after years of post-licensure surveillance.

Anybody can become a vaccinator as long as they’re supervised by an “experienced vaccinator”. Leaked documents reported in The Sun newspaper suggest vaccinators will be “trainee nurses, physios and paramedics” who are anticipated to deliver “tens of thousands” of vaccinations every day in five mass vaccination centres in the UK. On top of that there will be hundreds of mobile units operated by GPs and pharmacists which will deliver vaccines to the vulnerable and care homes. The military, in turn, will apparently be involved in the massive logistical operation of delivering vaccines to the centres and mobile units under the correct storage conditions that for some vaccines could be as low as minus 80 degrees Celsius. For the UK, the widely anticipated pre-Christmas roll-out assumes the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, based on an engineered, replication-deficient chimpanzee viral vector, sails through its Phase III trials and gets green lighted by the UK medicines regulator, the MHRA.

But contrary to news reports that talk about nurses, paramedics, physios, pharmacists and doctors being the vaccinators, the amended, post-consultation and final text of the Regulation doesn’t require vaccinators to have any background in the healthcare professions. This is presumably to keep options open for all eventualities, which may include shortages of healthcare professionals. But imagine how vaccinators with no healthcare background or training would respond if asked questions about the effectiveness, safety or contents of a vaccine? What if the military were called in for this particular duty? Would military personnel, who are more used to firing weapons designed to kill or maim, really be able to deliver the new generation of synthetic biology vaccines safely, painlessly and with sufficient knowledge that would allow them to legally support informed consent? Or are we just asking too much?

Let’s revisit the Magna Carta

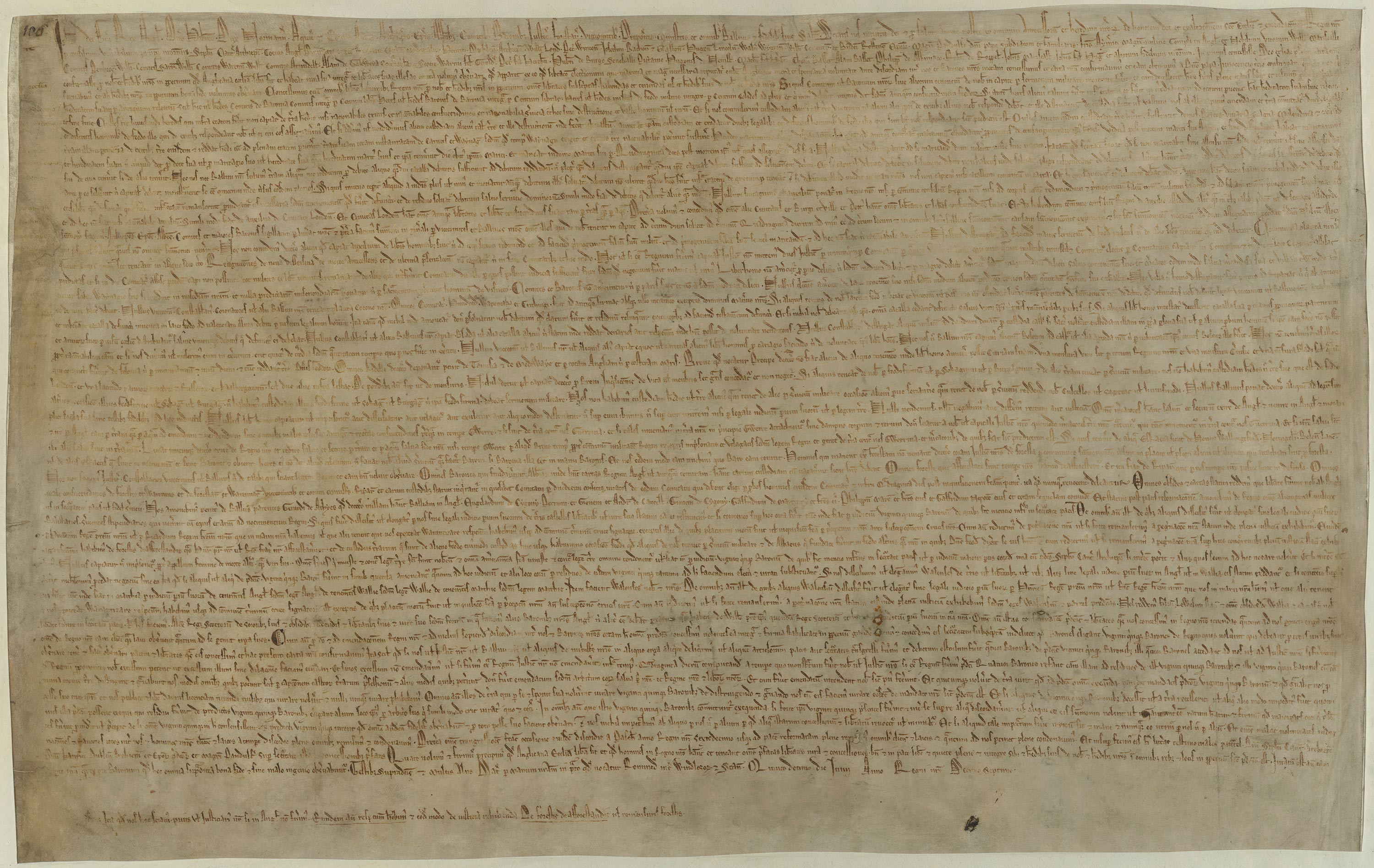

It was around 800 years ago that the Magna Carta Libertatum (Latin for the “Great Charter of Freedoms”) was signed as a royal charter by the unpopular King John at Runnymede, near Windsor, in 1215. Despite its rocky history and subsequent revisions, that culminated in it being integrated by Edward I into English statutory law in 1297, the Magna Carta is widely viewed as the foundation of an English (albeit unwritten) constitution, protection of the rights of the public and the basis of the emerging democratic process in the developing English Parliament.

Magna Carta 1215. Source: British Library

We are now at a critical time in history where government powers in relation to civil liberties need to be reviewed or the consequences could be traumatic and affect generations to come. Such reviews are likely to be accelerated by legal challenges, such as that of Simon Dolan’s now at appeal.

This requires dialogue with the public and due parliamentary process. An authoritarian Government supported by a mainstream media that acts as a propaganda mouthpiece for Government, coupled with widespread censorship of debate by social media platforms, and the suspension of parliamentary process – all factors that are very much in play today – set the seeds for deep social instability. It’s not good enough for the current Government to say ‘we can do as we like because we got in with a huge majority’.

Revisiting governmental powers over civil liberties, including our rights to the respect for private and family lives (Article 8, the Human Rights Act 1998) and freedom of expression (Article 10, the Human Rights Act 1998) — through the historical lens of the Magna Carta — would be a good start.

We await with bated breath the results of the appeal by entrepreneur Simon Dolan against the disproportionate response by the UK Government in its lockdown measures. Will there be a future legal challenge over the UK’s mass vaccination programme? We now some senior lawyers who are keeping a sharp eye on this. More in due course.

But let's not give up on Parliamentarians yet - Desmond Swayne MP - is one of very few who currently gets our full support for his views on coronavirus disproportionality!

Sir Desmond Swayne MP calls out "herd stupidity" and coronavirus fearmongering in Parliament (22 October 2020)

>>> Back to Covid: Adapt Don't Fight campaign

Comments

your voice counts

23 October 2020 at 4:16 pm

Brilliant observations by Desmond Swayne. I wish, however, he and people in general would take on board the scientific fact that viruses (including this one) are not contagious and CANNOT be transmitted by people. The key to the whole "pandemic" is environmental (air) pollution, which triggers the virus. The latter is a genetic expression with the sole function of adjusting the human microbiome in response to stresses caused to the environment by man-made air pollution in the form of toxins, herbicides, insecticides, pesticides, glyphosate, plastic in all its forms, formaldehyde, radiation etc. In other words, this virus in common with all other viruses is benign and represents our last line of defence. The "side effects" of the virus are caused by the toxins with which it binds when removing these from the human body which, of course, means that air pollution is the problem and nothing else. This also explains the new outbreaks of "infections"; they are not caused by interpersonal contact but by air pollution. This can easily be verified by testing the air quality in virus hotspots. The above is the truth based on state of the art science and, of course, means that the previous and current government measures, which are based on the absurd and totally discredited "Germ Theory" (an invention of the charlatan and fraudster Louis Pasteur) could not be more inappropriate and dangerous. Simply nothing makes sense about this so-called "pandemic".

25 October 2020 at 12:11 am

But surely if Covid-19 (and some other viruses) can be transmitted by droplets coming from the infected person's respiratory system, then it can be transmitted by kissing. It is in saliva, after all. Air pollution particles may carry the virus, and thus increase the chances of catching it in more polluted areas. It has been suggested that it may be carried in moist air from sewage as well. It can also be transmitted via surfaces then hands to faces and into the mouth or respiratory system, hence the gloves and the handwashing precautions. But perhaps someone could explain the pathological and cellular biological processes of this very different view of how this and other viruses function - it would be helpful.

25 October 2020 at 4:38 pm

Viruses cannot be transmitted by droplets or kissing. No virus can travel from one person to another person, i.e. viruses are peculiar to each person and cannot function in another person. Mucous (droplets) neutralises viruses and makes their transfer impossible. Viruses are everywhere, i.e. in the air, in water and also in sewage, but that does not mean they are dangerous. They bind with certain environmental toxins found in humans and work to eliminate these. They are the last line of defence and take over when the fungi and bacteria tasked with the removal of toxins are overwhelmed by these. In other words, they are benign and should not be suppressed. We should only deal with the "side effects" of this process, and in this conjunction it is important to identify the type of pollutant involved. For example, if it is a carbon particulate called PM 2.5 then cyanide is involved (the reason why many victims turn blue) and an immediate treatment for cyanide poisoning is required, which is easy and virtually always successful. Failing that the patient may die. The problem is never the virus but always the toxin with which it binds. I can provide you with the scientific papers or, otherwise, go on the Internet and watch the interviews with Dr. Zach Bush, the most brilliant medical scientist and doctor on the planet. You will find illuminating.

24 October 2020 at 9:21 am

Copied from Farcebook...

Wise words from the wonderful Miriam Margolyes;

“The United Kingdom has fallen. There has been a right wing coup in this country... . And nobody noticed. We did not notice because it was years in the making. We did not notice because when it came, it came in a blonde wig and a mask of buffoonery. We did not notice because it lied to us and hid its true intent. We did not notice because the foreign manipulation was hidden from us and continues to be hidden from us. We did not notice, because the lies when they were discovered were hidden by more lies, until lack of truth became normal and acceptable. We didn't notice because it appealed to our basest nature. It cried racist, it cried xenophobe, it falsified a threat to our way of life and blamed others. We did not notice because we accepted all the promises and lies and now we cannot admit to our gullibility.

Make no mistake it has been moving steadily and stealthily. Have you not noticed how Parliament has been emasculated and how decisions are now taken by a few in a closed room? Have you noticed how the judiciary is being sidelined? Have you noticed how the media are controlled & access to news is restricted? The BBC merely mouths faceless government sources and the papers howl racist xenophobic and government-fed lies?

Have you noticed how the police, under cover of COVID, are being encouraged gradually to interfere more and more in our lives? Have you noticed how we are being encouraged to report 'unsocial behaviour' in our neighbour's? Have you noticed how the impartial Civil Service is being packed with yes men and government cronies? Committee after committee is rigged with government-friendly sympathisers.

Even now a review of the Armed Services is underway. Have you noticed how every means of objection or complaint is being stealthily closed? Have you noticed the intention to lower food standards, animal & environmental standards and abandon the guarantees of our basic human rights? Have you noticed how measures trumpeted as keeping foreigners out, actually make it harder for US to leave? Finally have you noticed how the government is engineering circumstances under which everyone's lives will be so much harder and under which we will have so much more to worry about than complain about our government?

Meanwhile the rape and asset- stripping of the country has already begun, with million-pound contracts awarded to cronies with no apparent expertise, siphoning money from the public purse to the private pocket and delivering nothing.

It may already be too late but surely the time has come to cry enough! To stand up against the lies, the manipulation, the takeover of our Society. This government does not govern for the people; this government is governing for itself. It has become an enemy of the people, its actions are treasonous. Surely it is time to demand better, time to TAKE BACK CONTROL.”

24 October 2020 at 7:56 pm

2 years ago Hancock praised the fourth industrial revolution and its designer, Klaus Schwab (yes, the man behind World Economic Forum and this Great Reset event we now experience): https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-4th-industrial-revolution

Democracy is not suspended - it won't come back. Virus is only an excuse. Welcome to the new normal.

14 November 2020 at 3:13 pm

Apsolutly spot on.

25 October 2020 at 12:14 am

Quite a lot of people noticed this quite a while ago, but their voices were dismissed as being those of paranoid conspiracy theorists. Or they were just no listened to. And there were in particular all those politicians of all parties who failed to make the legal changes so desperately needed to secure our democracy, for decades. The real question is - where is the powerful upsurging pro-democracy movement?

10 November 2020 at 1:03 pm

Apart from Simon Dolan’s courageous court case, criminal prosecution of every MP is underway, spearheaded by Michael O’Bernicia. Each is being charged with fraud, treason and genocide. He has also instigated Magna Carta 2020.

https://www.thebernician.net/private-criminal-prosecution-of-parliament-top-legal-team-engaged/

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences