Can we jettison misguided and dangerous recommendations on fat and heart disease – please?

Australian research makes a splash

It’s not often that the mainstream media notices an academic meta-analysis, or study of studies – particularly if it goes against the tide of prevailing dietary advice. But that’s what happened with a recent Australian study, published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ).

Saturated fat: not so bad after all?

The BMJ paper was an update of a previous meta-analysis by the same investigators, looking at the consequences for cardiovascular health of replacing dietary saturated fats (i.e. butter) with polyunsaturated, omega-6 fatty acids (PUFAs). This time around, the group reassessed the results of the Sydney Diet Heart Study (SDHS), a randomized, controlled trial involving 458 patients that compared the rates of cardiovascular disease among subjects who increased the amount of omega-6 PUFAs – specifically, linoleic acid from safflower oil – in their diet with patients who continued their normal diet. As well as reanalyzing the results, the investigators incorporated them into their previous meta-analysis.

The SDHS results were clear: replacing dietary saturated fats with omega-6 PUFAs increased all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and mortality from coronary heart disease. Not only that, but, “An increase of 5% of food energy from [omega-6 PUFAs] predicted 35% and 29% higher risk of cardiovascular death and all cause mortality, respectively”. Similarly, the updated meta-analysis found that increasing dietary omega-6 PUFAs in isolation was associated with increased mortality risk from both coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease overall. And Omega-6’s are the main components of polyunsaturated fats in the Western diet – and they are found in vegetable oils and margarines — the very things we started to eat more of forty or so years ago when we were warned saturated fats would give us heart disease!

By contrast, the SDHS found that when dietary omega-3 PUFAs were increased alongside omega-6 PUFAs, to more closely resemble the 1:1 ratio enjoyed by our ancestors, both coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease risk were reduced.

Time for a new model

According to the prevailing dietary wisdom, this shouldn’t have happened – and the usual suspects are busily trying to pretend that they haven’t, although it’s notable that they can’t present a unified front on this one. Current mainstream recommendations hold fast to the ‘lipid hypothesis’, which proposes that the cholesterol found in saturated fats raises blood cholesterol, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) or ‘bad’ cholesterol. Because the mainstay of the theory is that raised blood LDL-C is a major contributor to atherosclerosis and heart disease, statin drugs can be considered the ‘golden child’ of the lipid hypothesis.

Oxidation is the key

Experts like Dr Dwight Lundell have for some time pointed to oxidation as the true culprit in atherosclerosis and heart disease. According to this alternative theory, dubbed the ‘degenerative hypothesis’, LDL-C only becomes a problem when it becomes oxidised. In fact, LDL-C is a misnomer, since all LDL molecules contain cholesterol. Far from being ‘bad’ in any way, LDL is absolutely vital for life, since the body uses it to transport important nutrients, including cholesterol, from the liver to tissues and organs.

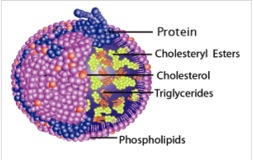

Lipoproteins, such as LDL, consist of a core of fats (triglycerides) and fat-soluble vitamins (Figure 1), surrounded by a phospholipid membrane penetrated by cholesterol molecules. In this way, water-insoluble cholesterol can be transported around the body in water-soluble lipoproteins. Some of the membrane lipids are delicate PUFAs, and these can become oxidised – and toxic – in people who eat a poor diet or don’t exercise, among other factors. Not only is oxidised LDL a sensitive marker for heart disease risk, it is strongly implicated in the development of atherosclerosis.

Figure 1. A lipoprotein molecule

Protecting the heart with saturated fats and antioxidants

Clearly, then, it follows from the degenerative hypothesis that a diet high in antioxidants will protect against LDL oxidation. Integrative medicine practitioner and ‘paleo diet’ advocate Chris Kresser describes the antioxidant glutathione as the ‘bulletproof vest’ that protects against dangerous oxidation. Glutathione-boosting strategies include exercise, cruciferous vegetables, sulphur-containing foods like garlic and onion, nutrients including alpha-lipoic acid, selenium, vitamins B12 and B6, folate and glycine, and botanicals such as milk thistle, cordyceps, gotu kola, and broccoli seed.

Also, since it is the delicate PUFAs in the LDL membrane that become oxidised, a diet high in PUFAs will increase the risk of oxidation, since more PUFAs will be available to be packaged into LDL membrane. This is especially true in modern, Western diets with their high omega-6:omega-3 PUFA ratios. On the other hand, saturated fats may well be protective, since their chemical structure makes them highly resistant to oxidation.

We’ve come a long way, baby

This new thinking is a long way from the theory that arteries are like pipes and cholesterol is sticky gunk that accumulates and eventually blocks them up. As an hormone precursor and constituent of cell membranes, cholesterol is vital to life, as is the crucial transporter LDL. Surely, it can’t be long before the medical establishment – or even dieticians – begins to take notice and catch up.

Comments

your voice counts

19 February 2013 at 3:17 pm

At last, things are starting to move in the right direction. Although the studies included in the meta-analysis are observational, when you bring a number of these types of studies together, they start to offer some useful insights.

I hope that things are going to turn round quickly and people can start to eat real food and regain their health.

17 August 2013 at 1:12 pm

Eye opening stuff. I always thought that a balanced diet with exercise was the best answer. I always had a gut feeling that whipped cream was good for you!

03 September 2014 at 7:25 pm

Meta-analysis? Seriously..? "Oxidation of LDL is the culprit" hardly disproves that excessive intake of saturated fat does not play a large role in increasing LDL. Am I wrong to think that if you have a higher LDL you have a more chances for the LDL to oxidize? You have thousands of holes in your arguement that unfortunately the average person cant spot. Do the world a favor and let more educated people analyse the information.

16 September 2014 at 7:07 pm

Hi Nathan, thanks for commenting. The major point of the article was that saturated fat has not only been unfairly demonised as the prime culprit in cardiovascular disease, but that – according to the degenerative theory – it may also act as a protective agent against oxidative damage to LDL. Interestingly, a newly published report suggests that oxidized LDL may even be beneficial, showing just what a developing field this is: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/09/140904121247.htm. We weren’t aiming to disprove the links between saturated fat intake, cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease. We’ll leave that to experts like Dr Malcolm Kendrick – http://drmalcolmkendrick.org/the-great-cholesterol-con/ – Dr Uffe Ravsnkov – http://www.ravnskov.nu/uffe.htm – Dr Aseem Malhotra – http://anhinternational.org/news/saturated-fat-myth-busted-in-british-medical-journal – or some of the maverick doctors covered in our earlier article – http://anhinternational.org/news/anh-feature-medical-mavericks-and-heart-disease. The first two are featured in the documentary $tatin Nation, which we’d strongly recommend: http://anhinternational.org/news/blowing-the-lid-on-statins-and-the-cholesterol-myth.

22 June 2020 at 10:19 pm

Good for you Nathan, I wiil go as far as saying that questioning everything and believing nothing is your motto life. Does your so called "educated people" fully understand the human body at a molecular level? Presumably not. You have been fed a load of dietry BS through out your entire life and suddendly you are an expert on what is sensible and what is not. Lastly, I will most certainly tell you and your so called educated people that you'll are wrong and yes you'll know absolutely nothing about LDL.

22 April 2015 at 3:24 am

There is so much misinformation and misdirection here, I don't know where to start. I'll just try to keep it simple. The supposed links to "scientific proof" were no such thing and did not prove your point. I agree that saturated fat is not as bad perhaps as has been touted, that doesn't mean it is good or protective. I agree that it is better than polyunsaturated oils and hydrogenated fats, but the truth is that no fats (separated from their source) are healthy. None of the studies have compared either kind of fat to no fat. Of course a diet low in fat and high in sugar and highly refined flour is not healthy but what about a diet low in fat and high in vegetables, whole grains, seeds, nuts and fruits? Doctors with superior results in bringing patients back from the brink who recommend this way of eating are John McDougall, Caldwell Esselstyn, Pam Popper, Neal Barnard, Michael Klaper, Dean Ornish, T. Colin Campbell among others.

15 May 2015 at 2:28 pm

It looks like we have a different view of the existing scientific evidence. You say “the truth is that no fats (separated from their source) are healthy”. Our view is that an extensive body of research on omega-3 fatty acids and growing body of research on medium chain triglycerides suggests otherwise. We agree that the Ornish/Willett type low fat diet has worked for a lot of people, but there is also good evidence that higher fat diets work in others, especially those who are very active, have adapted to fat-burning by reducing their carb intake and engaging in intermittent fasting, and ones who don’t have significant polymorphisms adversely affecting their lipid metabolism. This involves being ‘keto-adapted’ and displaying a state of ‘nutritional ketosis’ (ketone bodies in blood: 0.5 - 3 mmol/L) A useful review is by Volek, Phinney and Noakes, 2014: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17461391.2014.959564?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&;

22 October 2017 at 1:04 pm

Monounsaturated fats are just about as resistant to oxidation as saturated fats, so they are great too. I eat a lot of macadamia nuts for this reason. They are very high in MUFA and are quite low in PUFA.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences