While governments, dieticians and even many nutritionists still remain firmly bound to the “eat little and often” bandwagon, an increasing body of evidence is emerging suggesting the exact opposite gives most of us our best chance of long, healthy lifespans. The latest addition is a comprehensive study just published in the journal Cell Stem Cell from a group led by Prof Valter Longo – the gerontologist and cell biologist who has been at the forefront of research in this field.

The practical implications of Longo et al’s research can be summed in just three words: eat less food! What’s more, it’s clear that one of the essential steps to optimum health is simple, available to everyone and kind to your wallet. Here’s our quick guide to incorporating the latest research on fasting into your own lifestyle.

Longo lays it out

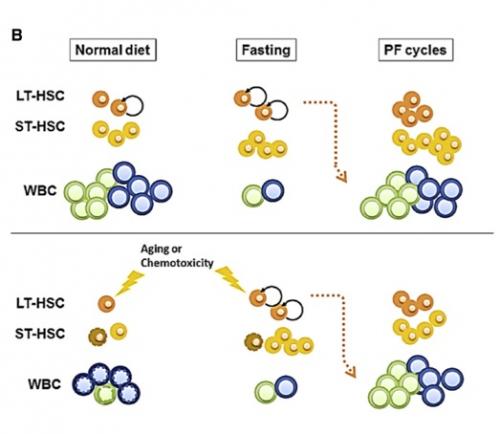

The latest comprehensive study by gerontologist Professor Valter Longo of the University of California shows effects from fasting that far exceed anything that can be delivered by drugs. The most dramatic finding of his group’s latest research was that six cycles of fasting and refeeding post-chemotherapy restored the white blood cell (WBC) levels of mice to near-normal levels, along with the ability of WBC stem cells to produce new WBCs (Figure 1). Positive effects of fasting occurred independently of chemotherapy and in ageing mice, and Prof Longo’s group also achieved promising results of repeat fasting in a Phase I trial of human chemotherapy patients.

Figure 1. How cycles of fasting are thought to restore white blood cells (WBC) and stem cells (LT-HSC and ST-HSC) in mice. Fasting leads to dramatic reductions in WBCs that are replenished upon refeeding, while also causing the self-renewal of stem cells to increase. The result is destruction of older immune cells and generation of new ones. Taken from Chen C-W et al. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 14: 810–23.

Exciting, not surprising, results

The exciting results of Prof Longo’s team add to the suspicion that we may have flourished because of, rather than in spite of, the historical lean times – that Nature’s boundless intelligence accounted for periods of scarcity or starvation in our internal wiring, our very DNA. Only in the modern era have we encountered ‘well stocked kitchen syndrome’; our ancestors couldn’t simply walk into a supermarket and fill a trolley with endless varieties of woolly mammoth. The evolutionary evidence is that caloric restriction is embedded into our developmental blueprint.

So it’s “bravo!” to Prof Longo. However, it would be a mistake to think that there are no benefits to fasting for less than the minimum 48 hours employed in his research. Central to the effectiveness of fasting is the mTOR (mammalian Target Of Rapamycin) system, a complex nutrient-sensing pathway that acts as the master controller of protein synthesis in the body. As ANH-Intl founder Robert Verkerk PhD stated in an earlier article, entitled ‘Protein kinases, caloric restriction and exercise’, “Dysregulation of mTOR, along with the diseases that occur as a result, is caused by inappropriate gene expression, in turn triggered by excessive exposure to insulin and nutrients, especially glucose”. In short, restricting caloric intake is the best way to bring the mTOR system back into balance.

The ANH-Intl's guide to fasting

Here is a starting guide to incorporating the principles of fasting into your own life, but please seek support from a health professional if you have or are concerned about a health issue:

- Maintain at least 5 hours between meals – and don’t snack in between! And drink only water between meals if possible. For many people, especially those with slower metabolic rates who are more prone to weight gain, eating twice a day, rather than the more commonly accepted three times a day, can be the best way forward

- Maintain an overnight fast of at least 12 hours, 6 days per week. Eating within a certain window of time achieves this almost effortlessly. While it’s particularly easy to achieve for those who choose to skip breakfast and have their first meal at (say) midday, it’s also readily achievable for the breakfasters who are prepared to have their evening meal (say) between 7 pm and 8 pm and their breakfast at 8 am the next morning, drinking only water in between

- Consider an 18-hour-plus fast twice per week – something that’s easily achieved simply by skipping a meal entirely. Different people have different preferences, and introducing exercise at the end of the fasting period can bring additional advantages. For many, say on a non-working day, having an early evening meal between 5 pm and 6 pm and exercising for an hour before eating at midday the next day works well. Alternatively, often better for working days, eating lunch between 12 pm and 1 pm, skipping the evening meal and breakfasting at 7 am the next day, is also easy to work into busy lifestyles

- Another option that works for many is ‘alternate day’ or ‘every other day’ fasting, where you eat a balanced and varied diet comprised of around 500 kcal/day for women and 600 kcal/day for men every second day, while eating normally on the other days

- Also popular is Dr Michael Mosley’s ‘fast diet’, AKA the 5:2 diet: eat normally for 5 days, and eat only one-quarter of your normal calorific intake on the other 2 days of the week.

These changes are in themselves not difficult to achieve, but require you to be committed and adapt your eating around social situations. It’s often a lot easier if all the adults in a given household work together on the same eating (and even exercise) schedules.

When you’re eating less often, it’s critical to be thinking carefully about the quality of the food you’re eating, and considering if any supplementary nutrients or botanicals are required. Find out more at Food4Health.

The importance of physical activity

Fasting, as wonderful as it is, is only part of the equation for those seeking optimum health. But food frequency and food quality only delivers part of the benefits available. Physical activity is also crucial, and for best results it needs to be adapted to the needs and capacity of the individual. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is one of the most time-efficient forms – and helps shift the body to build your mitochondrial reserve while helping the body switch to more efficient fat burning and reducing your chronic disease risk. Find out more.

As you’ll discover, our modern lifestyles – both sedentary and indulged by excessive simple carbohydrates and sugars – conspire to switch off our ancestral protein kinase signalling systems, namely the mTOR, AMPK and sirtuin pathways. These allow us to do what our genes are well adapted to do: shift effortlessly between cycles of feast, fasting and intense activity.

Fasting, then: a beautifully simple and evolutionarily preserved mechanism to lose weight, boost health, look and feel younger and live longer.

Please do what you can to get this message out, because you’re unlikely to be hearing it any time soon either as government advice or from your local doctor or dietician. Cynically, yet realistically, this is because neither the food nor pharmaceutical industries are set to benefit from it.

Comments

your voice counts

20 June 2014 at 2:14 pm

Please be aware that animal 'models' are extremely unreliable predictors of human physiology. The average agreement between human and non-human studies is about 50% - i.e. it is just as likely to be irrelevant as it is to be relevant.

You might as well toss a coin.

I would very much like to see ANH stop citing non-human studies.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences