By Rob Verkerk PhD, founder, executive and scientific director

Around one in 10 people on our planet (~ 800 million) go hungry every day. Most of these live in developing countries. Around 2 billion people, nearly 1 in three of us, even by conservative United Nations standards, suffer micronutrient deficiencies.

In the industrialised world, most people get enough food to meet the body’s basic energy requirements from the carbs, fats and protein they eat. But the composition of these macronutrients is often far from ideal – and they still don’t get enough micronutrients.

The latest UK data from the National Dietary and Nutrition Survey (2016) reveals some disturbing conclusions including the fact that most of the adult population consume close to the stipulated portions of fruit and vegetables (average: 4 portions/person), yet significant numbers of people suffer deficiencies of vitamin A, vitamin D, riboflavin, iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, iodine, selenium and zinc. These deficiencies are not based on the recommended daily allowances (or Nutrient reference values, or NRVs, as they’re now called in Europe), but on the Lowest Reference Nutrient Intakes, levels beneath which overt diseases and conditions linked to nutrient deficiency will occur.

This is yet more indirect evidence for the necessity of micronutrient supplementation in many people. Given this, it is astonishing that, with very few exceptions (e.g. folate for preconceptual women), governments remain so averse to the use of supplements when our society is awash with nutrient-deprived processed foods.

Government guidelines – no sea change in sight

Last week, I received a letter from a senior member of the UK’s Department of Health, in response to a letter I’d sent in early September to the UK Minister of Health, the Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt, questioning the UK government guidelines. The long and short of it is that the UK government is convinced that its advice is correct. It is also unwilling to make any changes at this stage. Neither of these things come as a surprise given the lengths governments go to in order to protect the food, biotech, agricultural and pharma industries that are direct beneficiaries of our poor relationship with food. Our governments might be thinking they’re doing us a favour: our sickness yields a healthy economy. But only until such time that the population becomes so disabled it can no longer be sufficiently productive. Or the healthcare system as we know it collapses because it is overburdened and underfunded.

Getting it wrong from the start

Many of the things we get wrong with our food – that end up dramatically increasing our disease risk as we get older – are ‘programmes’ set up in childhood. We know that poorer people in these countries eat less healthily, often trading nutrient-dense food for energy-dense ones. While there are a complex of reasons for this, over which there is still not any reason consensus.

If you analyse the cost of whole unprocessed food ingredients as compared to highly processed, packaged or junk foods, it’s easy to see that there is little basis for the view that those with lower socio-economic status (SES) can’t afford nutritious foods.

There are other processes going on that maintain this well-known gradient between SES and nutrition quality.

Among these are:

- Access to energy-dense, as compared with nutrient-dense, foods

- Food addiction

- Behavioural programming set up in childhood

- Lack of food preparation skills to cook whole foods from scratch

Access to high quality, nutritious food is a fundamental human right. In order to get societies eating healthier, it’s becoming abundantly clear we, the public – not governments – need to take matters into our own hands. Those of us with responsibility for children have not only a responsibility to find and consume food and nutrients that keep us healthy, we also have a responsibility to help children develop a healthy attitude to food.

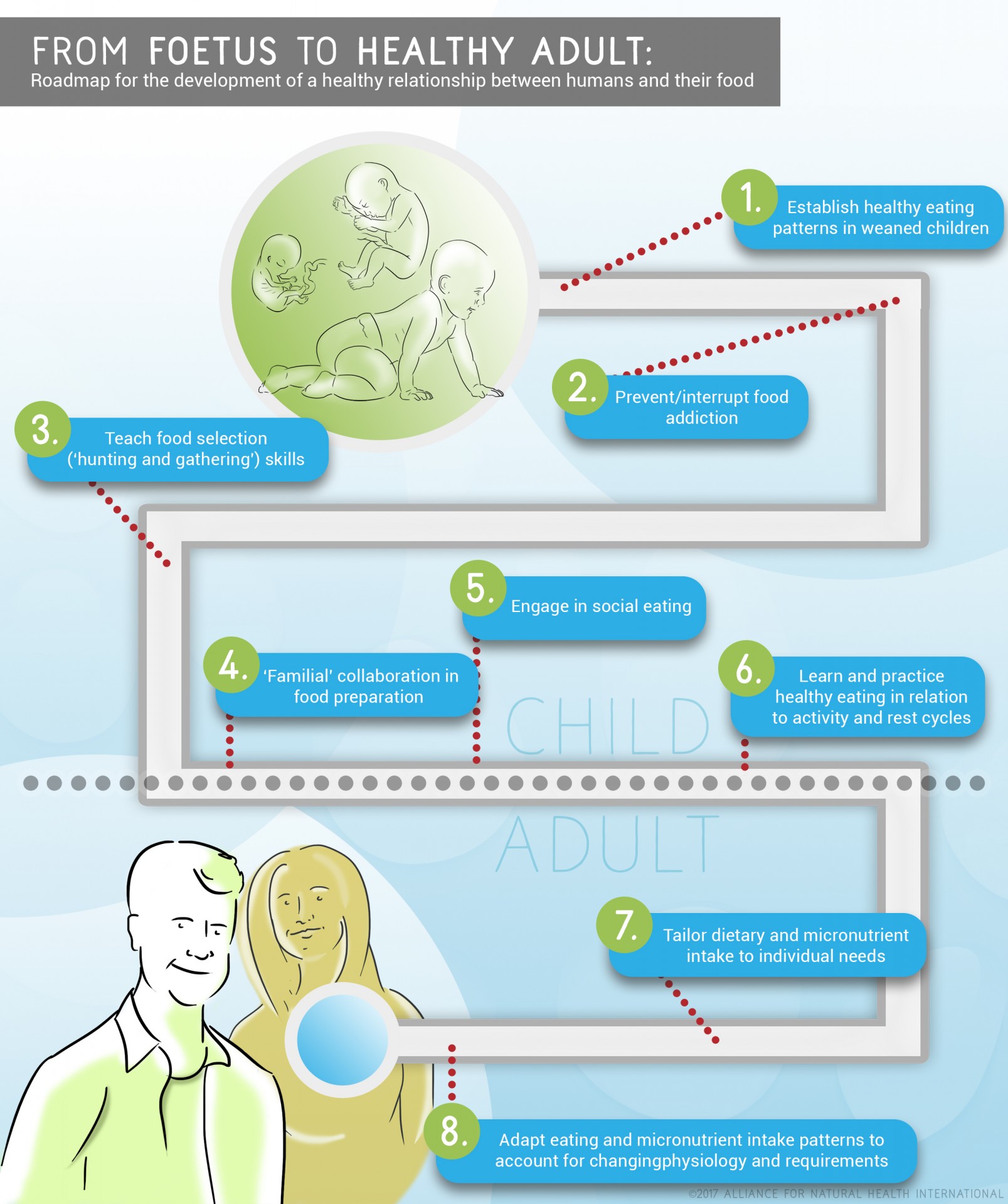

We propose that by focusing on six particular aspects in a child’s life, as highlighted in our Infographic below, we could dramatically influence the future health and resilience of our society. We can’t rely on schools to do it, as most are simply re-iterating government guidelines, the very approach to eating that is causing unprecedented levels of chronic disease. Instead, we must delegate this function to the community and familial levels, just as it was for our ancestors. This isn’t about going backwards, it’s about moving forward, and re-developing a relationship with natural, wholesome food that resonates with our evolutionary background.

About the infographic

- Establish healthy eating patterns in weaned children. A child’s palate is programmed from a very young age, the process beginning as soon as weaning starts. Children are biologically attracted to sweet foods – a phenomenon that aided our survival before sweet foods could be found on every street corner. Exposing a child to only bland, sweet energy-dense foods will result in that child being more likely to reject nutrient-dense, phytonutrient-rich foods as they get older.

- Prevent/interrupt food addiction. Food addiction that has both a physiological and psychological basis, is a much bigger problem than government authorities are prepared to admit. Addiction patterns and comfort eating are established in childhood. The result is children and adults that reject nutrient-dense foods in favour of energy-dense ones. This leads to the familiar pattern of metabolic diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes that are now rife in society. Given the reward patterns that are set up, mediated by changes in the dopaminergic circuitry and opioid receptor stimulation, associated with sugary foods, food addiction also increases the likelihood of substance abuse in later life.

- Teach food selection (‘hunting and gathering’) skills. Supermarkets are the places where most people shop. Children don’t always have sufficient involvement in food selection and discrimination. Many isles in a supermarket contain foods that have little value to human health, yet are highly addictive. We need to help our children to ‘hunt and gather’ in the world of plenty, helping the child to discriminate better, and understand the values and challenges associated with eating different foods. We strongly recommend the ANH-Intl Food4Kids Guidelines to assist food selection. Supporting this is our supermarket smart guide.

- ‘Familial’ collaboration in food preparation. Children learn by example. In a world of ready-made meals, two-parent families and processed foods, the skills of home food preparation are rapidly being lost. It’s time to turn the tide on this trend and get the kids back into the kitchen and learn life skills that will guarantee them a healthier future.

- Engage in social eating. More and more people have given up on the dining table. They eat on their laps, in cars, on the move, or in front of the television. When we eat with outers, we’re more likely to eat more slowly, mindfully and healthily than when we eat alone. Eating more slowly helps us better digest our food and support the all-important parasympathetic (‘rest and digest’) side of our autonomic nervous system.

- Learn and practice healthy eating in relation to activity and rest cycles. It's not just about eating the right foods. We also need to exercise to enjoy optimum health. Unhealthy eating behaviours and lack of exercise often go hand in hand. However, we need to ensure that where we are exercising we are eating in a way that supports our bodies to get the most benefit from exercise as well as ensuring we rest and recover properly.

- Tailor dietary and micronutrient intake to individual needs. Everyone is different, even identical twins. although we may have the same genes we have different lifestyles, stressors and eating habits, which impact on our resilience. In an ideal world we would get all the nutrients we need from our food, but this isn't always possible. Visit a functional medicine practitioner or nutritional therapist to understand better how your health status may be improved by changing your diet, your lifestyle and, potentially, providing appropriate supplementation.

- Adapt dietary and micronutrient intake patterns to account for changing physiology, environment and requirements. Consume a nutrient-dense diet following the 10 pointers as per our Food4Health guidelines. Fundamentally, food provides information for our bodies. It contains thousands of individual naturally occurring substances that help our bodies perform optimally. Our needs change as we go through different times in our life and we need to adapt the way we eat and supplement (when necessary) to compensate.

Comments

your voice counts

12 October 2017 at 12:49 am

..most of the adult population consume close to the stipulated portions of fruit and vegetables (average: 4 portions/person), This is total nonsense based on the fake RDAs.eg. If healthy we need 30X the Vit C RDA and if sick.. 150X that measly 100mgs., to fully rev-up our leukocytes. Clark H R PhD ND.. 90% of B vitamins are destroyed by even a slight heating such as a stir-fry. 50% of phytonutrients are destroyed in a short boil and 100% in a 10min boil. Minerals are chucked out with the boiled water. Micronutrients are tightly bound in the cells of raw veges, that's why cows need 2 stomachs. Juicer's blades heat up releasing DNA smashing chromium and carcinogenic nickel.. The only veg I eat for health is sauerkraut for the probiotics.

18 October 2017 at 4:22 pm

Thank you for bringing more information to this topic for me. I’m truly grateful and really impressed. Absolutely this article is incredible. And it is so beautiful.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences