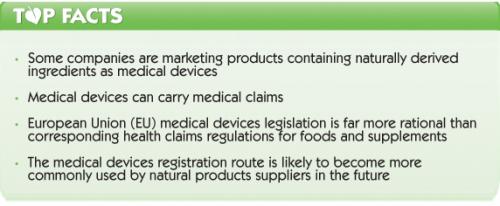

In 2014, commercial freedom of speech in the European Union (EU) is so restricted that manufacturers of foods and food ingredients are severely limited in what they can say about the health benefits of their products. The key culprit is, of course the EU health claims legislation and its scientific arbitrator, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). So how are some companies bringing products to market as medical devices that contain naturally derived ingredients and carry approved medical claims – rather than health claims? And could it represent an opportunity for the natural products industry?

When cranberry becomes a medical device

A good example of this Alice Through The Looking Glass scenario is a cranberry extract called Cranberry Active, manufactured by Medical Brands and found in its i say: range of products. Cranberry Active is, its maker proudly proclaims, the “1st self-care medical device for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infections,” with a “proven anti-adhesion capacity against the bacteria and is an effective treatment that does not burden your body”. It’s also a medical device. By comparison, poor old cranberry itself has a grand total of zero authorised health claims on the European Commission’s (EC’s) official register of health claims on foods and food ingredients, despite 16 attempts.

This bears repeating: we are not allowed to hear of the potential health benefits of cranberries themselves, nor of any food supplement products derived from cranberries. This arises from the EC’s professed desire, expressed in the Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation (NHCR; No. 1924/2006), to protect consumers from “false, ambiguous or misleading” health claims, and from EFSA’s slash-and-burn approach to scientific substantiation. Yet cranberry products sold as medical devices can carry claims to both prevent and treat urinary tract infections. Nice work!

Lifting the lid on medical devices regulations

The critical piece of legislation is Council Directive 93/42/EEC. This defines a medical device as “any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, material or other article, whether used alone or in combination...intended by the manufacturer to be used for human beings for the purpose of diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease...”, among other uses. To classify as a medical device and not a medicine under the terms of EC Directive 2001/83/EC, Directive 93/42/EEC states that a product must “not achieve its principal intended action in or on the human body by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means, but which may be assisted in its function by such means”. Translated, this effectively means that medical devices must have primarily physical mechanisms of action, and Cranberry Active ticks all the boxes.

Medical devices: loophole or an example of sane EU regulation?

One particularly interesting feature of EU medical devices legislation is its classification of devices according to the risk they pose to the user: “based on the vulnerability of the human body taking account of the potential risks associated with the technical design and manufacture of the devices,” as Directive 93/42/EEC puts it. Class I medical devices are considered low risk, and the manufacturers themselves can perform the ‘conformity assessment procedures’ necessary to ensure that it meets the Directive’s requirements. Anything higher than Class I requires progressively more comprehensive input from a ‘notified body’. Notified bodies are private companies certified to carry out the assessment by each Member State’s competent authority – for instance, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK. They need not be located in the applicant’s home territory.

All this means that the legislative framework for EU medical devices ends up being far more sensible than that for health claims on foods or botanicals. There are three main reasons for this:

- There are no ‘negative’ or ‘positive’ lists limiting which types of medical device can be sold in the EU, in contrast to health claims and ingredients used in food supplements

- Because the notified body and not the competent authority makes the final decision as to whether each medical device meets the terms of the legislation, medical devices are not subject to a generic pre-market approval process – unlike health claims

- The risk-based classification system used in lieu of these options makes rational sense. Actually, a somewhat similar approach has been proposed as a more appropriate way of regulating herbal and traditional medicinal products used by practitioners, developed jointly by ANH-Intl and the European Benefyt Foundation.

How long these advantages will remain in the face of renewed EC and Parliamentary scrutiny is anyone’s guess, however.

Implications for the natural products industry

Not surprisingly, the marketing of naturally derived products as medical devices has stirred its fair share of controversy. While the Netherlands-based Medical Brands has been remarkably astute in its product development, even applying to a German notified body, toys have been seen issuing from the prams of other, less successful, operators.

Some of this success may be related to Medical Brands’ membership of the Association of the European Self-Medication Industry (AESGP) – an arm of the pharmaceutical industry and one of the prime movers behind the unfit for purpose Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (THMPD). That said, the medical devices route does presently offer a parallel, alternative path to market for naturally derived products, albeit limited to products that can demonstrate a primarily physical mechanism of action.

But since disproportionate, irrational and unnecessary restrictions have been applied to health claims on foods and food ingredients, it is inevitable that the medical devices route will become more frequently used – as long as it remains both feasible and available.

Comments

your voice counts

10 September 2014 at 8:46 pm

The media in NZ have reported on a recent item in The Times indicating that the EU has labeled lavender oil as toxic and requiring all manufacturers using it in their products to show which molecules in it are allergens - all 600 of them according to the report! How do you see this in relation to the above item?

I have been growing lavender, manufacturing natural products and direct marketing for nearly 10 years now and never had a customer with an allergic reaction,

It seems to me that the EU approach is rather like using a sledge hammer when the careful use of a tack hammer is all that is required.

11 September 2014 at 4:04 pm

Hi Russell! This story relates to the EU's REACH regulations - standing for Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of CHemical substances - and is quite concerning for lavender lovers and producers. In fact, there are implications for all essential oil products, and we'll be looking at this issue in more depth next week.

13 September 2014 at 2:42 pm

So an orally consumed cranberry capsule licenced as a medical device can claim UTI prevention as long as it has primarily a physical mechanism of action yet an orally consumed cranberry capsule that effects a physical mechanism of action cannot make a claim....absurd!

29 September 2014 at 12:32 pm

Self-Care Medical Devices regulation is implemented since july 1994. This include products as nasal sprays, vaginal lubricants, wound dressings based upon honey and many other products.

Only since EFSA had negative opinion about cranberry the food industry is searching for escape routes.

The medical device regulation always has been here only the food industry never realised it.

Same applies to Medicines Act, Today Wart Removal products can be Drug (salicylic Acid) or Medical Device (TCA). Again nobody is aware.....

TCA is 3x more effective compared to Salicylic Acid, which makes this medical device more effective!

The industry today lack's regulatory and science competence.... Where can you study medical devices? it is not even part of Pharmacy or healthcare studies.... So how can you develop these products if you do not understand physical mode of action? As a result the pharmaceutical industry has been developing pharmaceutical, immunological or metabolic products to be able to communicate a medical claim. Why?

Feel free to comment me...... (if you understand Medical Devices)

30 January 2015 at 11:32 am

Hi Maikel. Thank you for your comment, please accept our apologies for the slow response. Your concerns are very similar to Rob Verkerk’s. We’ve been involved in medical device work through our sister organisation, Alliance for Natural Health Consultancy, and now refer any medical device work to Trevor Lewis (http://www.medicaldeviceconsultancy.co.uk/?id=5). May we ask what your involvement is? Maybe you would consider writing a piece for the ANH website about your concerns?

19 April 2015 at 9:11 pm

Non pharmacological action on cranberry?: Well it is taken orally: liberation, absorption, ditribution, metabolism, excretion... Does it sound to us. Yes, that is pure basics of pharmacology.

Its effect is done by proanthocyanidins potent antioxidants that appear to be able to decrease bacterial adherence to the bladder epithelium cells. So it is not a mechanical effect as cranberries must be affected by phisiological body actions and so acts agains bacteria due to pharmacological actioan and metabolism or at least physicochemical (but not only "physical")

We are fed up of companies trying to surpase medicines control offering products as medical devices or food suplements; when they look for pharmacological effects.

If you want to treat and infection for non mechanical procedures (rinse), please present as medicines. Else we will find that more medicines will be taken to the medical devices or food suplements to try to avoid deep clinical trials. As you must realize that tehy try to present as a Class I medical device. Amzing! and fakes/scamms.

Thank you

19 January 2016 at 4:32 pm

Maikel, Why on earth would the food industry otherwise be interested in medicines legislation. Food legislation covered perfectly well (and safely) FOOD supplements including plants (herbs, botanicals whatever pharma legislators want to call them now) for decades. The UK's issue (due to TCM/imports) was poor enforcement; poor crack down on adulterated/poor quality importers/retailers (never been any safety concern with any UK-made supplement). Since THMPD & now NHCR, ingredients/products sold safely for decades (as supplements) cannot inform customers what they do...yet pay the authority (via drug legislation) and amazingly the exact same ingredient that had "no evidence" of efficacy, is now efficacious. It's money grabbing red tape, nothing to do with patient safety that it was designed for; nobody ever died from a UK food supplement, prescription medicines kill more than illegal drugs, if they were concerned about health the authorities would stop pumping symptom-masking drugs down our throat and look at the cause of preventable disease... health food (without a claim) anyone!?

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences