Content Sections

- ● Fuel efficiency and the Food4Health Plate

- ● How do you burn your fuel?

- ● Anaerobic glycolysis of each glucose molecule yields just two ATP molecules

- ● Aerobic glycolysis of each glucose molecule yields an additional 34 ATP molecules

- ● Oxidation of proteins and fats

- ● Nutritional ketosis

- ● Getting flexible nutritionally and physically

- ● Transitioning from being a carb burner to a fat burner

- ● Planning for health

- ● Further reading:

This week saw the Calorie Reduction Summit take place in London. As it’s Throwback Thursday, we thought it was a perfect time to reiterate why counting calories is a waste of time and anything but a solution for the obesity crisis.

Everyone knows obesity and type 2 diabetes are reaching crisis point globally. Governments are panicking; healthcare systems are overwhelmed; scientists and experts are in dialogue. In fact, it’s talked about so often that people are getting more and more desensitised and less motivated to take their own weight management actions. At ANH-Intl, we prefer to focus on making our 'engine' as flexible and resilient as possible. The body can then fix itself in most instances.

Despite evidence to the contrary, some mainstream experts continue to peddle the calories in/out argument – usually hand in hand with calls for a low fat/high carb diet. Another story, for another day!

However, calorie counting fails because not all calories are created equal. In the same way as a car, the type of fuel you put in is much more important than how much. Below we summarise how our bodies make and use the fuel from the foods we eat to save you counting calories and help you to become more metabolically flexible and resilient — which is the route to vibrant health!

Fuel efficiency and the Food4Health Plate

By Rob Verkerk PhD

Founder, executive & scientific director

You’ll understand from the Food4Health guidelines that we at ANH are strongly of the opinion that most people, with the support of government guidelines, consume a balance of too many carbs and not enough healthy fats.

Much of this has been the effect of public health advice by governments, supported by Big Food, to consume low-fat diets. More and more evidence is confirming our understanding that consuming little fat and lots of carbs, especially refined ones, and even consuming too much protein, stops you from becoming what we call ‘keto-adapted’, meaning you are an efficient fat burner.

In a high-fat nutshell, the dormancy of our fat burning capacity, a condition facing millions, is a major, and often unspoken, contributor to the present obesity epidemic and chronic disease spiral. Governments and most medical doctors, and especially Big Food and Big Pharma, are not ready to tell this story. There’s too much money to be made by keeping us in the dark. With today’s knowledge, it’s verging on criminal.

How do you burn your fuel?

Over millennia, our bodies have developed very intelligent systems for turning the food we eat into the energy we need to run all of our internal metabolism. That includes building new DNA and cells, running our brains and immune systems (that are among the two biggest energy sinks we have), digesting our food — and all of that (and much more) before we even become active and fuel our mitochondria, the energy-generating ‘factories’ we have in nearly every cell in our body, especially our muscles!

Let’s look at carbs first, given that governments tell us they should represent the primary source of our energy.

Anaerobic glycolysis of each glucose molecule yields just two ATP molecules

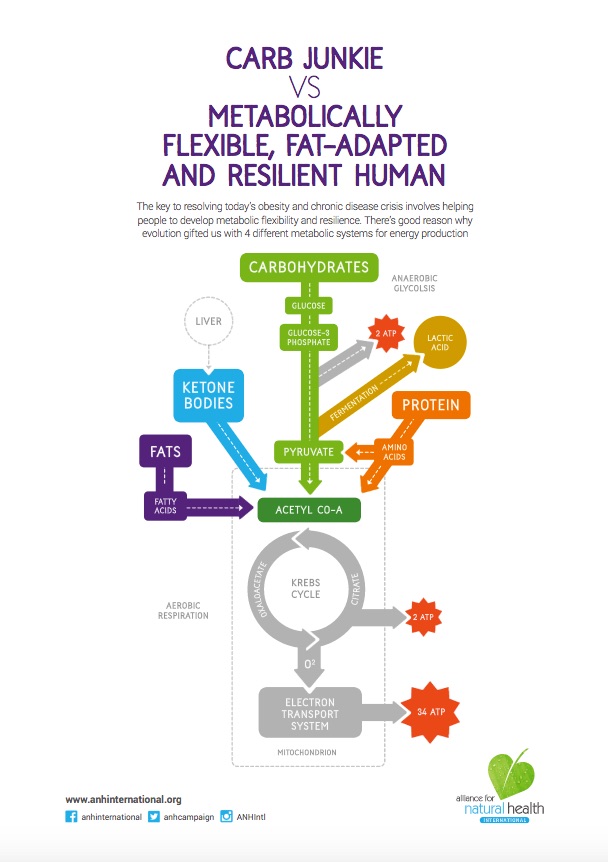

Carbs are basically long chains, simple or complex, of glucose. We get energy from glucose (a 6-carbon sugar) by breaking down each molecule into smaller pieces. We refer to this process as glycolysis which literally means ‘sugar splitting’. In the absence of oxygen (anaerobic glycolysis), every molecule of glucose generates very limited amounts of energy in the form of ATP and pyruvic acid (pyruvate) both of which can be utilised by our body to provide energy.

In the absence of oxygen, such as when you’re exercising for extended periods close to your maximum limit, you start to ferment pyruvate, yielding lactic acid (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Key energy-yielding pathways for cellular respiration of macronutrients and ketone bodies

While ATP is the primary fuel used for most reactions in the body most of the time, this small amount of energy from anaerobic glycolysis is used mainly to produce energy carriers like NADH and FADH2.

Let’s not forget, we need a lot of ATP, in the order of half or more of your body weight’s worth daily! Some of this we get from our food, some we get by recycling ATP.

Aerobic glycolysis of each glucose molecule yields an additional 34 ATP molecules

Put oxygen into the equation and it’s a very different story. If you are replete with oxygen, and are therefore not exercising near your limit and exceeding your lactate threshold, you get to burn your carbs via the aerobic glycolysis pathway. Here, the pyruvate is used as a key substrate for the Kreb’s (citric acid) cycle that goes on in mitochondria.

Another point is that we can store glucose, but not very much of it. We do this in the form of glycogen. We can store around 100 grams of glycogen in the liver and about 400 grams in the muscles. Most people have burned this up after around 90 mins of strenuous activity in the absence of other fuel.

Now, what about proteins and fats?

Oxidation of proteins and fats

They also get oxidised to form energy in the form of ATP. What is key to appreciate is that the oxidation of proteins and fats, as seen in Figure 1, also converge on the Kreb’s cycle. In the case of proteins, they must be oxidised to their constituent amino acids (of which there are 20 in total), and have their nitrogen removed in order to become substrates that are used directly or indirectly in the Krebs cycle.

Gram for gram protein yields about the same amount of energy as carbohydrates. That’s one of the reasons food labelling laws require that manufacturers stipulate that 4 calories (kcal) are yielded for every gram of carb or protein contained in a food. Actually, that’s the case if you both absorb and oxidise the fuel fully. The problem is many people don’t digest, absorb or oxidise their fuels fully because of one or more impairments, these being genetic or physiological.

“One molecule of fat yields…..how many ATP molecules?”

Let’s leave the best to last! Fats yield energy from oxidation too and the products of oxidation, just like carbs and protein, converge on the Kreb’s cycle. Fats are broken down to their constituent fatty acids via the beta-oxidation pathway, mainly in the liver. They then yield the common denominator acetyl-coA via 4 reactions that occur again in the mitochondria (and peroxisomes), mainly in the liver and muscles.

Nutritional ketosis

But that’s not all. If we reduce the amount of carbohydrate consumed, especially while the energy requirement is increased (i.e. as a result of exercise), more acetyl-coA will be produced. If there is more than is required the excess will be shunted into another process called ketogenesis, that yields ketone bodies (acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate and acetone). These then become an additional metabolic fuel.

From an evolutionary perspective, this pathway has been vital to human success and is clear evidence for just how well we are adapted to starvation and what we now think of as ‘intermittent fasting’ (i.e NOT three meals a day with snacks in between). Without carbs, proteins and fats from our food, in other words during starvation, we can actually use ketone bodies produced by beta-oxidation of our own fat deposits as our primary fuel for vital organs such as the brain and heart. Do it for too long and raise your ketone levels too high, you….die. A good enough reason to ensure starvation is not maintained!

For a long time, scientists and doctors thought of ketosis, the process that generates ketone bodies, as a bad thing. That’s because it was associated with either starvation, or uncontrolled diabetics, who can develop serious and life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis.

As shown by Drs Jeff Volek and Steve Phinney in their bestselling book, The Art and Science of Low Carb Living, healthy, nutritional ketosis is established when serum (blood) concentrations of ketone bodies are in the range 0.5-3.0 mM. This is what they refer to as the “optimal ketone zone” and can be achieved with a low carb, relatively high fat, ketogenic diet, such as that consumed when you follow the Food4Health Plate Guidelines.

As far as storage and use of proteins and fats are concerned, if we don’t have enough carbs in our body, and we haven’t adapted to burning fats we can start burning protein, especially in muscles. This is never a good thing, especially if you’re interested in improving your lean muscle mass and being physically very active.

We’re all aware of how readily we store energy as fat. We also know that the main reason people get fat is not from eating too much fat, but by eating too little —and too much carbohydrate. Fat can exist in many forms and is stored in different ways and places including beneath the skin (as adipose tissue) or around the organs (as visceral fat). Generally the latter is the most dangerous and needn’t be that visible, hence concerns about the risk of being ‘skinny fat’ i.e. thin on the outside, fat on the inside. This, once again, an increasingly common predicament triggered by low fat recommendations leading to dependence and addiction to refined carbs and other ultra-processed, high glycaemic foods.

Getting flexible nutritionally and physically

So far we’ve looked at how the body uses different types of fuel. What we now have to understand is that physical activity and exercise has a huge bearing on how this happens. In essence, the body can use one of three different energy systems while you exercise.

If you exercise extremely vigorously for a few seconds you rely on producing ATP, the universal fuel, from creatine phosphate of which you have very limited reserves in muscles. The plusses of this is that it makes energy instantly. Its downside is it doesn’t make very much.

The second system is the anaerobic glycolysis pathway discussed earlier (Fig 1) which makes energy from glucose in the absence of oxygen. It can’t be sustained for more than about 5 minutes or so before the lactate accumulates excessively. Cramp is one outcome of being anaerobic too long.

The third system is the key one for long-term energy use. It’s the aerobic pathway that lets us burn any of the three major macronutrient fuels. But it’s the fats that are both the cleanest burning and, as we’ve seen above, yield by far the most energy.

Transitioning from being a carb burner to a fat burner

The ease to which you can shift from being primarily reliant on carb burning, as compared with being a keto-adapted, fat burner, varies considerably in different people. But assuming all things are even and that impediments to changing your lifestyle significantly are absent, there are a number of key practical steps you can take that will often have a dramatic effect in your transition. These include:

- Avoid snacks of any type between meals, especially ones that are rich in simple carbs (it’s okay to drink water)

- Maintain at least a 12-hour overnight fast on at least 5 days a week. Alternatively, you may want to engage in ‘time-restricted feeding’, for example, limiting all your food consumption to say an 8 or 10 hour eating window during the day

- Leave at least 5 hours between meals or any form of food intake to allow the body to fast and avoid pushing it into low-grade inflammation

- Engage in high intensity physical activity (if your level of fitness permits it) for short periods (say 15 to 45 minutes) around twice weekly. High intensity interval training (HIIT is a good option

- Engage in some periods—say three times a week—of longer, lower intensity endurance exercise (in excess of 1.5 hours on each occasion)

- Consume at least 25 g of protein and perhaps 5 g of glutamine and 5 g of branched-chain amino acids within a 30-minute window following completion of intense exercise to help your muscles to recover

- Stretch those muscles that have been worked carefully after bouts of intense and extended exercise

- Rest sufficiently between bouts of exercise, so that your muscles can rebuild and compensate following the damage caused by the exercise.

Planning for health

Getting the balance between your nutritional intake and your physical activity regime right is both an art and a science. It’s also highly individual, given variations in genetics, aptitude, opportunity and environment, amongst other factors.

Keeping a food and training diary can be very helpful, as can monitoring your progress in various physical pursuits, be it as times to complete given circuits, your heart rate using a heart rate monitor, or a description of how you feel after the activity.

Integrating these approaches into your life is the best way of experiencing a very high level of vital health. However, that’s easier said than done given time and other constraints that apply to so many of us.

The point is doing something right is always better than doing nothing right. So make a start….today!

For the full, detailed version (with all the science) of the above article click here.

Obesity Fix part 1

Obesity Fix part 2

Further reading:

30 Mar 2018 ANH-Intl releases updated healthy eating advice

07 Mar 2018 Are governments deliberately on the wrong anti obesity track?

08 Apr 2015 ANH-Intl’s four plate shoot-out

04 Feb 2015 ANH Food4Health Plate: the starting point for metabolic flexibility

21 Jan 2015 ANH-Intl Feature: Re-thinking your food choices for 2015

Comments

your voice counts

29 June 2018 at 10:31 am

There seem to be differing opinions on oil and fat consumption in the presence of arterial plaques. Any ideas on what to do? Should these foods be avoided?

02 July 2018 at 11:39 am

Hi Danny,

In our view, the most important diet for someone with atherosclerosis would be an anti-inflammatory diet, that has a healthy balance of macronutrients, plenty of plant secondary metabolites (such as polyphenols) - and that may include a healthy fatty acid profile of saturated fats. MCTs are saturated but are metabolised via different pathways to long-chain fatty acids. Palmitic acid can be harmful in large amounts, but its negative effects are moderated by palmitoleic acid, which is found in whole milk (and sea buckthorn, Peruvian anchovies, etc) but not in skimmed milk. A good marker of inflammation in the body is hsCRP while the harmful aspect of LDL that may increase with certain diets that are rich in saturated fats are oxidised small particle fractions (i.e. oxVLDL, or oxidised very low density lipoprotein). We hope this is helpful.

Best Wishes Rob

Rob Verkerk PhD

29 June 2018 at 8:41 pm

Unfortunately well-meaning parents & grand-parents cannot wait to get new born babies addicted to sugar via processed foods and sweetened drinks. This 'caring without thinking' behaviour means that youngsters become easily addicted to sugar and as a consequence, record numbers of British children are having their teeth extracted under general anaesthetic - it's criminal! We recently encountered a young mum wheeling a toddler down the isle of a supermarket - and the happy looking child was munching away on half a cucumber! A very refreshing site indeed, and sadly all too rare these days.

01 July 2018 at 12:34 pm

Hi Michael, that's great to hear! A sight that's not see too often at all.

We all as a society need to move away from seeing sugar as a reward or a treat. Unfortunately, we're up against our genetic programming as sugar was in short supply and as a high calorie food, our genes implore us to gorge on it when we can as a survival strategy. We're genetically programmed for famine not for feast, but too many of us are living in an age of plenty when it comes to food, where sugar becomes a poison that's now threatening our survival.

Cucumbers don't quite fit the treat bill as something sweet and chocolatey, but all that's needed is some creative thinking to come up with rewards that aren't edible!

Best wishes

Meleni

30 June 2018 at 9:06 am

AS ALWAYS EXCELLENT++++ information.

How do we get the mainstream to listen? do the NECESSARY?

I am putting a copy of this ARTICLE in a Health Complaint Lodgement I am currently working on/adding too.

Who knows? worth a try. and combined with paperwork/information that I had all the usual disastrous complaints, as did my sons - despite following the Government Food Pyramid and other advices from "experts, Researchers" and making every effort to keep abreast and care for my family to the very best levels I could, and living very "healthy lives" eg., exercise, activities etc., I also cut off all fat re meats, (which I am sure this & other "guidelines" I am sure made my family sitting ducks for these metabolic disorders.

In the Lodgement i have proof positive that my health has and is in the "fine tuning" of after much of body parts/health restored/rejuvenated! For example, removing Diverticulitis (moderate), Colonoscopy Nov., 2000.

Second (2nd) Colonoscopy Sep't., 2015 - NO SIGN OF ANY Diverticulitis and despite all the infections from undiagnosed/untreated Systemic Candida for over 25 years, and so much else re Health "interruptions" and wrong diagnosis's and treatments too.

I am in awe of the human body.

A southern Californian International Company who provides amongst other services, QUALITY synergised food based - Meds, - I call them Meds now, not Supplements, provided crucial treatments and maintenance for the excellent health I now enjoy and treasure more than ever.

How a Government agency shall handle that proof of following a certain health/food/treatment path that diverges from their promulgations shall be, I am not sure, but shall certainly hold my interest and shall keep you -ANH posted, if you so want that feedback..

Some Doctors were "disappointed" that I do not have Diabetes, Heart problems, Cataracts the list goes on , one Dr asked me what other illnesses I had once, and I asked "such as" he rattled of the above and more. I won't write here what I said to him.

Now I have my Dr writing in his notes new information (not typing into his computer) I give him and he has for sometime, and other Drs "allow" themselves to show surprise and regard for my health status as they do the requested Tests I asked for in 2015 to ascertain what was REAL reason that I had been ill for so long. some Drs even ask me what I am doing! I smile and tell them "NOT what you do".

Regards to all at ANH,

Deirdre

01 July 2018 at 12:28 pm

Thank you so much for your support and sharing your positive story. I have one too, which is why I do what I do here at ANH! Please let us know if you need anything else from us to support your documentation.

All the best

Meleni

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences